The Coronavirus Pandemic and Retirement Security

Why retiring early in the face of COVID-19 may spell bad news for your plan.

Editor’s note: Read the latest on how the coronavirus is rattling the markets and what investors can do to navigate it.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, at least one retirement trend was headed in the right direction: More workers were staying on the job longer, and that was good news for retirement security.

But COVID-19 has stopped that trend in its tracks. An accumulating body of data reflects an acceleration of early retirement as jobless older workers give up on the labor market due to the unique health barriers posed by the coronavirus.

This trend will be bad news for the retirement prospects of millions of Americans. People who retire early and claim Social Security well ahead of their full retirement age accept sharp reductions in their annual benefits. They also miss the opportunity to save for retirement during late-career years--which are often peak earning years and sometimes an opportunity to make catch-up contributions to fortify nest eggs. Finally, early retirees may need to stretch savings over more years.

Add it all up and you have the danger of a declining standard of living for many retirees. Let’s consider the recent trends, along with some ways to keep income flowing if you find yourself forcibly retired earlier than you’d hoped. Finally, I’ll offer a few thoughts on policy responses that could soften the blow.

Accelerating Early Retirement Older workers are telling pollsters that they plan to work longer as a result of the recession. For example, 37% of baby boomers and 39% of respondents from Generation X say they have delayed retirement or were considering doing so, according to a "Covid-19 & Retirement" survey by TD Ameritrade.

But that may be wishful thinking. Far more likely, long recession-induced layoffs, age discrimination, and the health risks older people generally face will combine to produce a major wave of early retirement. Meanwhile, in this unique recession, older workers must weigh the outsize risk to their health associated with employment. Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that adults over age 65 who become infected by COVID-19 are at higher risk of severe illness than others.

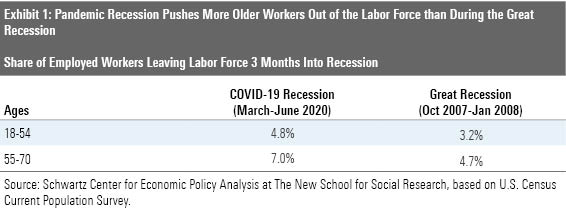

A new report from The New School's Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis found that 50% more older workers (or about three million people) have been forced into early retirement due to the pandemic-driven recession than after the onset of the Great Recession.

"The one-two punch of job loss and health risk is fueling older workers' early and unplanned exit from the labor market," said Teresa Ghilarducci, director of SCEPA. "Given a deep recession and a long wait for a vaccine, this trend is likely to continue, and a generation of people unable to save enough for retirement will face life-long decreases in their living standards."

SCEPA found that 2.9 million older workers have left the labor force since March and are at risk of having to retire involuntarily, and that another 1.1 million are likely to leave the labor force over the coming three months.

The economic damage will be widespread. The heaviest toll will be felt by people of color and those with lower income, who are experiencing higher jobless rates in this recession. But the damage will hit higher-income workers, too, according to another SCEPA report.

That research looked at people with earnings above the cap on wages subject to Social Security payroll taxes ($137,700 this year). It concludes that while a smaller share of these workers is likely to lose their jobs in the pandemic, they are more reliant on savings to maintain their standard of living in retirement than lower-income counterparts are. Social Security's benefit formula is progressive, replacing a smaller share of wages for high-income workers.

SCEPA also found that a significant share of higher-income workers have not saved anything for retirement--the figure was 27% before the pandemic. This group represents only about 4 million out of 67 million people in older households, but the pandemic recession will double the number of high earners expected to experience downward mobility into poverty in retirement, increasing from 360,000 to 720,000 people, according to SCEPA.

"Sadly, the COVID-19 recession makes clear that not even higher-income people are immune from the failures of our retirement system," said Ghilarducci. “Like people at all income levels, high-income households suffer from a systemic lack of retirement coverage at work. With all the burden of saving on the employee, high-income individuals must save large sums--often in the millions--to avoid experiencing downward mobility in old age. Combined with higher spending and often unrealistic expectations of working longer, high-income people are surprisingly vulnerable."

She adds that SCEPA’s forecast points toward twice as many high-income individuals falling into poverty or near poverty when they retire.

Strategies to Keep Income Flowing When people hear the advice to delay retirement, many hear that as "work forever" or "never claim Social Security before age 70." But that's not really the point--any delay at all is beneficial, notes Steve Vernon, a former actuary and author of the new book "Don't Go Broke in Retirement: A Simple Plan to Build Lifetime Retirement Income."

“If people who find themselves in tough straits due to the recession can possibly delay drawing Social Security for even a couple months or a year or two, they’ll reap advantages,” he says. “I’d look at every other opportunity to find money to live on. I realize this can be tough. But some kind of part-time work is one possibility. Also, make sure you're getting any of the unemployment benefits that are available to you.”

One silver lining in the current job market is the rising number of employers who will be more open to remote work arrangements, often on a part-time or contract basis, says Kerry Hannon, an expert on career transitions, entrepreneurship and retirement and author of the forthcoming book "Great Pajama Jobs: Your Complete Guide to Working from Home."

“This time of mandated shuttered offices is getting more employers to warm up to this idea,” she says. Technology skills will be especially important in these work arrangements, she adds. “When you work remotely that might mean learning new computer programs and communication tools, such as web conferencing, and video chats, and making sure your typing skills are up to par.”

Hannon also urges bringing some creativity to bear in thinking about your work if you are seeking out a part-time gig.

“You don’t need to replicate your old job,” she says. “How can you redeploy existing skills? You may already have the skills that will help make it work for you,” she adds, citing as examples organizational skills, an ability to focus, self-discipline, communication skills (both verbal and written), time-management skills, and the ability to work independently.

Hannon suggests checking out the career sections of companies that interest you, or sites of companies that specialize in connecting workers with work-from-home jobs. These include Flexjobs.com, Remote.com, and Wahve.com.

Policy Changes It's too early to predict the policy responses we might see to the retirement security problems created by the pandemic: Much will depend on the outcome of the makeup of Congress--and the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

But here are some ideas that can help address the problems created by an early retirement wave.

Health insurance: A recent study found that 5.4 million American workers lost their health insurance just between February and May. Older workers who lose their jobs before becoming eligible for Medicare (age 65) will need to rely on coverage available through the Affordable Care Act, assuming that law survives the Republican-sponsored challenge now before the U.S. Supreme Court. In some states, laid-off workers will be able to get Medicaid coverage under the ACA, while others will need to buy policies priced according to the law's scaled subsidies.

A much more robust approach would be to reduce the age of Medicare eligibility to 55. Democratic presidential standard-bearer Joe Biden has called for expanding access to Medicare by reducing the eligibility age to 60, but a good case can be made for moving lower still.

Social Security: For starters, let's not backpedal by making Social Security benefits less valuable than they are now.

Some policymakers have pushed to raise Social Security’s full retirement age--the point at which you can receive 100% of your earned benefit--to solve the program’s long-term financial shortfall. That idea relies on the flawed assertion that “we’re all living longer” and should therefore wait longer to receive a full benefit.

The reality is that workers of color earn less, have lower life expectancies, and tend to work in physically demanding occupations that become more difficult to continue at older ages. One recent paper by a team of economists notes that half of Black workers aged 55-62 reported in 2014 that they have jobs requiring "lots of physical effort," compared with just 32% percent of whites. Making these workers wait longer to receive a full benefit would not be equitable.

Another idea worth considering is an update to the current early retirement reductions, which have not been revised since 1956. When you file at the earliest age, 62, you'll receive 75% of your annual full benefit; every 12 months of delay past your full retirement age (currently around 66, depending on your year of birth) gets you an additional 8% annually until you turn 70.

Social Security Works, the advocacy group, has proposed bumping the percentage of full benefit a worker could receive at age 62 to 85%, gradually rising to 100% at full retirement age.

Learn more: I spoke with Kerry Hannon about strategies for finding part-time and remote work in the pandemic economy on this edition of my podcast.

Mark Miller is a journalist and author who writes about trends in retirement and aging. He is a columnist for Reuters and also contributes to WealthManagement.com and the AARP magazine. He publishes a weekly newsletter on news and trends in the field at Retirement Revised. The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BZ4OD6RTORCJHCWPWXAQWZ7RQE.png)