Small Value Stocks: Peril and Opportunity

Their fates lie at the heart of today’s economic debate.

Editor’s note: Read the latest on how the coronavirus is rattling the markets and what investors can do to navigate it.

Sometimes, stock markets have an indicator--a segment that encapsulates the era’s key investment issue. Two decades ago, technology stocks fulfilled the role, as investors wondered just how high the new economy’s earnings might grow. Technology companies fueled the 1990s’ rally, then led the ensuing collapse. Several years later, banks came to the fore, sinking the overall market with multiple bankruptcies, before stabilizing, so that stock prices could recover.

Small value stocks are today’s barometer. The main concern entering the New Millennium was whether technology stocks had become too richly priced. Approaching the global financial crisis, the question was whether all banks would implode. For those questions, small value stocks could offer few answers. However, their fortunes are irrevocably linked with today’s key questions. Will the recession be brief, or will it persist? When it does conclude, will the economy look as it did before?

Economically Exposed A glance at the characteristics of Morningstar's Small Value index explains the importance of the initial query. These companies are vulnerable. Even at peak conditions, most small value firms are relatively unprofitable. Nor are they financially robust, recording an average grade of C+ on Morningstar's Financial Health measure (the market norm being B+). These problems might be manageable if their revenues were recession-resistant. Unfortunately, they are not. Almost 60% of the Small Value Index's companies operate cyclical businesses.

Another indication of economic sensitivity: Morningstar's Economic Moat score, which sorts stocks into three buckets. Those companies judged by Morningstar's equity analysts to be well positioned against competition receive a "wide moat" designation, those believed to possess some defenses are marked as "narrow moat," and those bereft of protection have "no moat." No company in the Small Value index qualifies as having a wide moat. Just under 40% of those receiving scores (not all stocks are graded) have no moat, as opposed to 10% for the overall market.

Besides a rapid recovery, small value companies seek a return to normalcy. Some forecast that the experience with COVID-19 will forever alter American habits, as high-tech applications replace brick-and-mortar locations. Shopping will continue to move online; office spaces will become virtual; business travel will be curtailed. That is splendid news for companies on the cutting edge. Few such firms, however, exist within the small value group. In general, its constituents occupy traditional industries. For example, most of the nation's REITs are classified as small value.

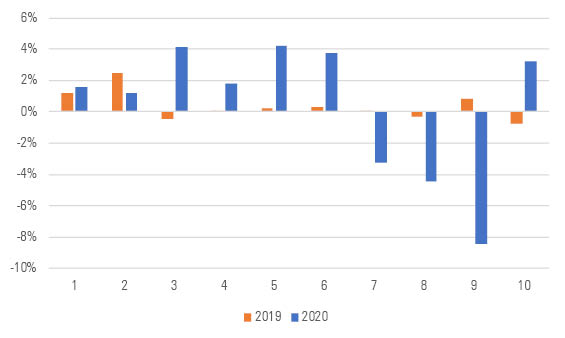

That investors have not reached a consensus on either the length of the recession, or the extent to which old-line industries will recover, is demonstrated by small value stocks’ performances, which have been exceedingly volatile. Consider the daily returns of Morningstar’s Small Value index during the first 10 trading days of June 2020, as opposed to 12 months before.

Exhibit 1: Small Value Volatility Is Way Up (Daily Returns for Morningstar Small Value Index, Now versus One Year Ago)

Source: Morningstar Direct

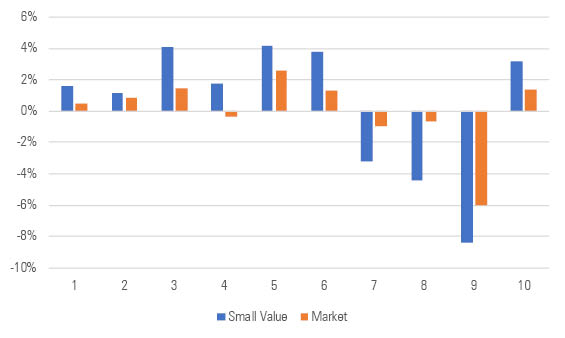

Those results are so far apart that they seem to come from different asset classes. To be sure, some of this year’s additional volatility owes to changing circumstances; all stock performances are unsettled. But small value has become the riskiest U.S. stock-market sector, by a wide margin. Compare its daily totals with those of the overall market, once again over June’s first 10 trading days.

Exhibit 2: Riskier Than the Overall Market (Daily Returns for Morningstar Small Value Index and Morningstar Market Index)

Source: Morningstar Analysts

Trading Places To an extent, this behavior puzzles me. As I have indicated, the economics make sense. What I do not understand is how these stock-market gyrations occur in practice. Frequently, large companies are traded in baskets, through futures contracts or exchange-traded funds. Such transactions can spur sharp, rapid price changes across an assembly of stocks, since a single transaction affects the whole group.

However, smaller firms are not typically traded in batches, at least not through investment vehicles. The leading general small-company ETF possesses $40 billion, while the top small value ETF controls $12 billion. Those figures are relatively modest. Neither do small-company futures attract great attention. Without these mechanisms to accelerate the effects of trading, it would seem difficult to push the small value index by several percentage points, within a single day. Yet such movements have become commonplace.

I suspect that the answer to the trading mystery is twofold. First, because most small value stocks are deeply illiquid, even modest buying or selling pressure can send them skidding across the pricing ice. Second, the shortage of trading mechanisms hampers attempts at arbitrage. That is, bargain-hunters who stabilize prices during declines may do so only for a few selected holdings, rather than support the entire group through a futures or ETF transaction.

The Gamble Regardless of the details, the big picture is apparent: Small value stocks are as volatile (if not more so) as they ever have been, mainly because of fundamental reasons. Trading peculiarities may be exaggerating the movements, but the underlying concern about the long-term future of small value companies is widespread, and it doesn't seem to be going away anytime soon.

In uncertainty lies opportunity. Small value issues have sharply lagged other equities, returning 1.5% annualized over the past five years versus the overall market’s gain of 9.8%. Much of that shortfall owes to diminished investor expectations. Should the economic news favor small value companies, with a short recession leading to a conventional recovery, then small value stocks could perform very well indeed, supported by both the economic bounce and higher investor sentiment.

Against that proposition rests the very real possibility that the coronavirus pandemic will linger, thereby permanently changing consumer habits and business practices. As always, opportunity is accompanied by peril. At least in this case, though, the investment positions are clear. Those who hold small value stocks should have no illusions about which conditions will help their investments--and which will not.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HE2XT5SV5ZBU5MOM6PPYWRIGP4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/AET2BGC3RFCFRD4YOXDBBVVYS4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T5SLJLNMQRACFMJWTEWY5NEI4Y.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)