The Uncertainty of Retirement Planning

Time can wreak havoc on even the best-laid plans.

From Z to A My friend Javier Estrada, professor of finance at IESE Business School in Barcelona, sent me his latest working paper, "Retirement Planning: From Z to A." As suggested by its title, the article advocates that investors work backward. They should begin their plans upon entering the work force, by specifying their desired income during retirement. Once that is known, and an asset allocation is specified, the required contribution rate can be calculated.

This process is aspirational. That is, while Javier's model is fixed, providing investment returns, contribution amounts, and withdrawal rates with assurance, investors enjoy no such confidence. As young adults, they know neither what the financial markets will bring nor (yet) what income will meet their retirement needs. Their lives lie ahead of them.

The point of the paper is to change the investor's mindset. Javier wishes to combat the standard practice of keeping one's head down, contributing to retirement accounts according to perceived ability, then looking up as retirement approaches and wondering what the accumulated assets will be able to afford. Better to know that answer ahead of time. To be sure, investment reality will confound the initial assumptions. That is fine; the plan can always be adjusted.

As is customary with research that relies upon a model, the paper's sensitivity analysis is particularly instructive.

For Starters The base case is an investor who will work for 40 years, then retire for another three decades. Javier's hypothetical citizen seeks $60,000 in annual retirement income, expressed in current dollars. (He sets Social Security, pensions, and other potential income sources aside. The paper is intended as an illustration, not as an actual financial plan.) The investor also seeks to leave a $300,000 bequest.

The investor settles upon an initial asset allocation of 60% S&P 500 and 40% 10-year Treasury notes that shifts upon the retirement date to the cautious blend of 40% stocks/60% notes. Those investments are free, which is a reasonable premise, given that one can create such portfolios today by combining Fidelity ZERO Large Cap Index FNILX with directly held 10-year Treasuries. The assets will perform according to the long-term averages. Stocks will gain 6.5% annualized, Treasuries 1.9%. (All the paper's figures are real, not nominal.)

The model recommends an annual contribution of $9,079. Doing so will create a lump-sum investment of $1.143 million on the retirement date. That amount will gradually decrease as assets are withdrawn (although the portfolio will be partially recompensed by investment gains), until $300,000 remains after year 70, at which time the investor conveniently expires and the bequest is granted.

What If? Impossibly neat, of course. But before addressing uncertainty by testing different investment returns, let's see how the investor could improve his outcome by altering his behavior. The first question: Would he be better served by raising his contribution rate by 10%, or by bumping his stock allocation from 60% to 70%?

My intuition misled me. Generally, the correct response to such questions is, "You can't allocate your way to success." Not this time. Hiking the contribution rate grew the nest egg by 10%, while expanding the stock position did so by 12%. The reason: The stock increase of 10 percentage points raised the portfolio's equity weighting by 16.7%. With equities so sharply outgaining Treasury notes in Javier's model, the allocation shift was surprisingly powerful (surprising at least to me).

Javier also tinkered with the investor's behavior during retirement, thereby leading to the second question. Which strategy leads to a higher estate, 1) reducing the annual withdrawal amount by 10%, from $60,000 to $54,000, or 2) increasing the in-retirement stock allocation from 40% to 50%?

That problem looked suspiciously familiar. As before, the first option offered a 10% benefit from adjusting the contribution/withdrawal decision, while the second featured a greater-than-10% increase in the portfolio's holdings of higher-performing equities. In this case, however, changing the allocation proved less effective than adjusting the spending rate. As it turns out, the math during the withdrawal phase differs from the math during the accumulation period.

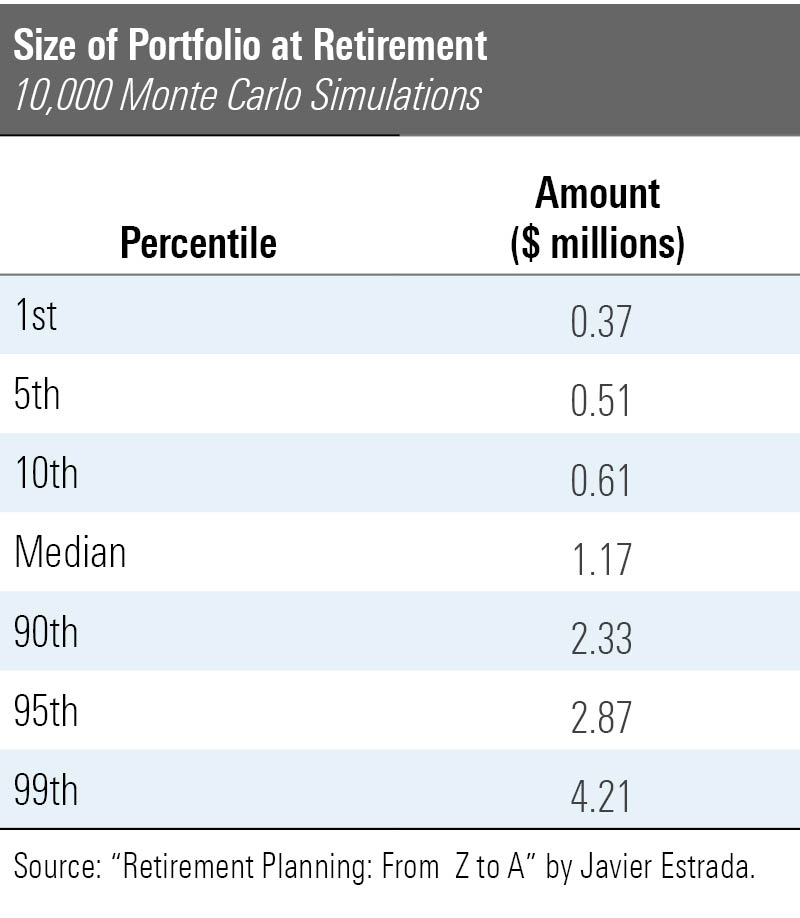

Ten Thousand Spins Now for the fun stuff: Varying the investment returns. Javier generated 10,000 simulations, using the same expected investment returns, standard deviations, and correlations as with the base case, but drawing randomly from a distribution of such performances rather than using a single, ongoing average. Below are the first, fifth, 10th, 90th, 95th, and 99th percentiles for the plan balance at retirement, along with the median. (Because simulations fluctuate, the median does not exactly match the base case.)

That's dramatic! The good news is that even at the fifth percentile, the investor could salvage his retirement by substantially raising contributions while also downsizing his retirement expectations (or working longer). The bad news is that Javier's computation assumes that history will vaguely repeat, by having the asset classes maintain their distribution. In truth, they could perform worse yet.

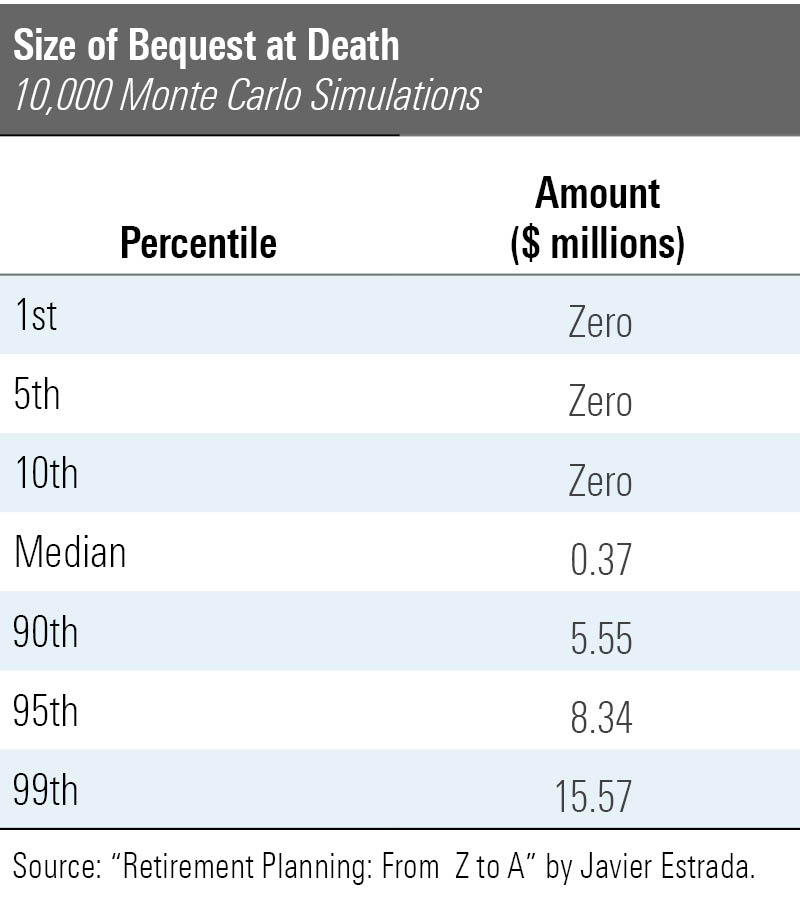

The percentiles for the bequest range so widely as to be comical.

Such is the nature of 70-year projections. The outcomes diverge so greatly as to thwart any analysis. Although the goal was a modest $300,000, the test suggests more than a 10% chance of exceeding $5 million. On the other hand, the investor left nothing at all behind on 42.9% of the simulations. It's helpful for young adults to consider whether they might eventually wish to leave money behind, and to appreciate that if so, they will need to accumulate excess savings, but addressing the issue more specifically seems impossible. Clarity can only come with time.

Although radical in its suggestion that novice investors plan all the way to the end--what other publications recommend extending the investment time horizon until the year 2090?--"Retirement Planning: From Z to A" implicitly advocates somewhat more conventional wisdom. The best retirement plans are managed iteratively, as blueprints developed by looking ahead become modified by what has occurred in the recent past. From Z to A, then back to Z. Repeat as required.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BZ4OD6RTORCJHCWPWXAQWZ7RQE.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)