Does the Case for Stocks Still Stand?

Market crashes dampen--but don’t eliminate--the long-term appeal of stocks.

Editor’s note: Read the latest on how the coronavirus is rattling the markets and what investors can do to navigate it.

The pandemic-driven stock-market nosedive of 2020 serves as a stark reminder not only that market crashes happen, but that they do so with a greater frequency than we might expect, as Morningstar's Paul Kaplan recently observed. Indeed, with this latest market drop, it's arguable that the case for stocks is less compelling over recent decades than we've been led to believe.

We’ve all been trained to invest heavily in “stocks for the long run,” as Wharton professor Jeremy Siegel first proclaimed in the 1990s in his book with the same title. That’s certainly true based on the theoretical underpinnings of the equity-risk premium. And it’s also true based on the empirical return data, as long as you look back a very long time. Market commentators (including our own) often like to cite the comparative returns of stocks, bonds, and bills going back to 1926, a period over which stocks have amassed a huge advantage. But pragmatically speaking, a century is a tad too long a time horizon to be useful for most investors.

How does the case for stocks hold up if instead we look at the past 35 years, starting in 1985? While somewhat arbitrary, I picked this start date for two reasons: first, it encompasses the full time span of a current-day late- to middle-aged investor; and second, it covers four major market crashes (1987, 2000-02, 2007-09, and the 2020 drop). I compared the S&P 500 with a traditional balanced portfolio composed of 60% S&P 500/40% Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index, based on both total returns and Sharpe ratio, a risk-adjusted performance measure. I ran the numbers through the end of April 2020, which incorporates the pandemic downturn but also much of the recent bounceback.

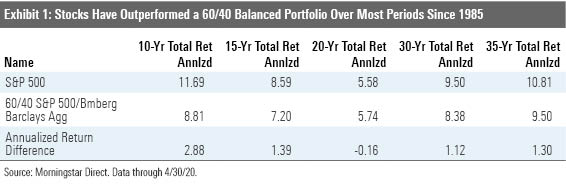

On a total-return basis, over trailing 10-, 15-, 20-, 30-, and 35-year periods, the stock index maintains an advantage over the balanced portfolio, but the edge is only just more than 100 basis points annualized for several periods (Exhibit 1). The biggest advantage emerges over the 10-year period (nearly 3 percentage points), while over the 20-year period the balanced portfolio actually edges out stocks.

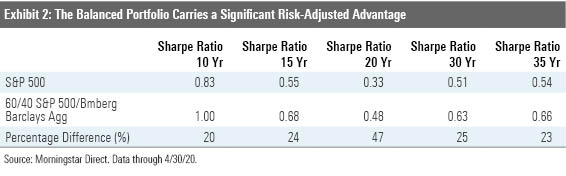

On a risk-adjusted basis, however, the balanced portfolio wins out over every period. While Sharpe ratio figures are not the most intuitive to interpret on an absolute basis, the advantage was 20% or greater for each period--a substantial level (Exhibit 2).

Using static periods does make them subject to considerable timing effects. For example, the 20-year period is the weakest for stocks on an absolute and risk-adjusted basis. But if someone started investing in 2003 instead of 2000 (missing the bursting of the tech bubble), the results for stocks would instead be far superior. To smooth out those effects, I also ran the same metrics through rolling 10-year periods on a monthly basis starting in May 1995. Results were roughly similar. Out of 301 10-year periods observed, 241, or 80%, saw the S&P 500 outperform the balanced portfolio. For Sharpe ratios, the balanced portfolio outperformed 100% of the time.

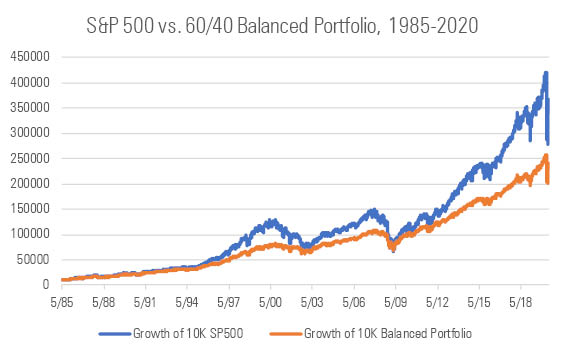

Implications and Actions I don't want to discount the value of even a relatively small advantage for stocks over the balanced portfolio when it comes to compounding returns over the long term. For example, an investor who put $10,000 in the market in May 1985 would have averaged only 130 basis points per year more than the investor who bought the 60/40 portfolio, but the ending value of that portfolio would have been around $120,000 higher. Of course, the balanced portfolio provided a much smoother ride (see Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Stocks Create More Wealth, but the Ride Is Much Bumpier

It’s also important to acknowledge the unusually strong role played by intermediate-term bond returns over the past few decades, driven in no small part by the steady march downward of interest rates. Mathematically, with interest rates as low as they are currently, it’s hard to imagine bonds providing anything like that level of return in near term; but over the long term, who can really predict the course of market cycles? Bonds also do a lot of their grunt work as safe havens precisely during those times when equity markets nosedive.

But we also should not discount the importance of risk-adjusted returns. Harry Markowitz won a Nobel Prize for a reason. We know that behaviorally, the volatility of the stock market leads many investors to make poor decisions. After the Great Recession, a broad swath of investors feared putting their money in the stock market, thus missing out on a good portion of the subsequent bull market.

So, working on the assumption that market crashes will happen, and to such a degree that the utility of a pure-stock portfolio may be significantly lessened for many investors relative to a balanced stock/bond portfolio, what are some approaches investors can take? Depending on your own personality and risk capacity, here are a few suggestions:

Tune it Out: For investors who intellectually prefer a higher-equity approach but psychologically recognize that they react emotionally to market volatility, one solution is to construct a system that limits the inputs of market chatter and/or the ability to rashly make changes. For instance, set-it-and-forget options like target-date funds (which are options in most retirement plans but are also available to investors who aren't yet retired) are ideal for cultivating a kind of inertia that can be beneficial. An even more restrictive version of this approach would be to place your money in a discretionary account with an advisor, where you essentially sign over authority to your advisor after agreeing on an investment approach. Ultimately, though, I think the most important step is to cultivate a kind of intentionally Zen-like mindset about market movements, which can be accomplished in part by avoiding a focus on daily market news. When people ask me, "What did the market do today?" I'm usually happy to reply, "I have no idea." Similarly, it can be helpful to avoid looking at investment account statements, particularly if they are for long-term accounts. Other than for an annual review, you'll be better off filing away the envelopes unopened.

Take a Balanced Approach: For those investors who just find the thought of market crashes too stomach-churning and emotionally devastating to tolerate, it just might make more sense to enjoy the smoother ride and risk-adjusted benefits of a balanced fund. Whether that involves a traditional 60/40 stock/bond mix such as I modeled above, or a more aggressive or more conservative mix, depends much on your goals, risk tolerance, and risk capacity. A target-date fund also serves this purpose in a more dynamic way, as it increases the proportion of your asset mix in bonds as you get older. I took the balanced approach myself when helping my teenage daughter invest some savings she had accumulated. Although her age alone would probably dictate a 100% stock allocation, I knew that she was very nervous about the prospect of losing money, so we decided on a low-cost, index-based allocation fund that invests 80% in stocks and 20% in bonds--just enough to smooth the edges of market declines.

Think Opportunistically: Hardier, more risk-loving investors may take the occasion of severe market dives as an opportunity to seek bargains. This is not a plug for buying on the dip or market-timing. But historically, market crashes have been periods where great investors get a chance to shine. While this could mean plowing more money into the market--one would need to have cash on the sidelines to do so--there are subtler ways to take advantage. Investors in company retirement plans could increase their contribution rates, for example. Indeed, one benefit of contributing regularly to your employer-based retirement plan is that you automatically keep investing during down markets. One could also rebalance a portfolio countercyclically, such as by topping up stocks to your policy weights in your portfolio or shifting allocations to styles or sectors that have fallen farther. Investors who aspire to this mindset can train themselves to embrace the excitement of market volatility, according to Morningstar behavioral economist Sarah Newcomb.

Ultimately, there's no single correct answer to the question of whether to go all-in on stocks or take a more-balanced approach. It comes down to your own priorities, goals, risk tolerance, and definitions of success. But whatever approach you take, make sure you internalize the notion of market crashes: It's not a matter of if another crash will happen, but when.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2e13370a-bbfe-4142-bc61-d08beec5fd8c.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/F2S5UYTO5JG4FOO3S7LPAAIGO4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/7TFN7NDQ5ZHI3PCISRCSC75K5U.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/QFQHXAHS7NCLFPIIBXZZZWXMXA.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2e13370a-bbfe-4142-bc61-d08beec5fd8c.jpg)