Currency Hedging: Fine for Bonds, Not for Stocks

The currency headwinds for unhedged equity exposure won't continue forever.

The question of whether to hedge currency exposure is one of the longer-running debates in investing circles. Some argue that currencies are part of the opportunity set and therefore one should leave currency unhedged, as it promotes diversification. But others see currency movements as too idiosyncratic to manage. To them, it makes more sense to hedge that risk away.

Here’s my take: Leave your foreign equity holdings unhedged but consider hedging your bond stake. In the rest of this piece, I’ll explain my rationale and the role risk tolerance can play in deciding whether to hedge or not.

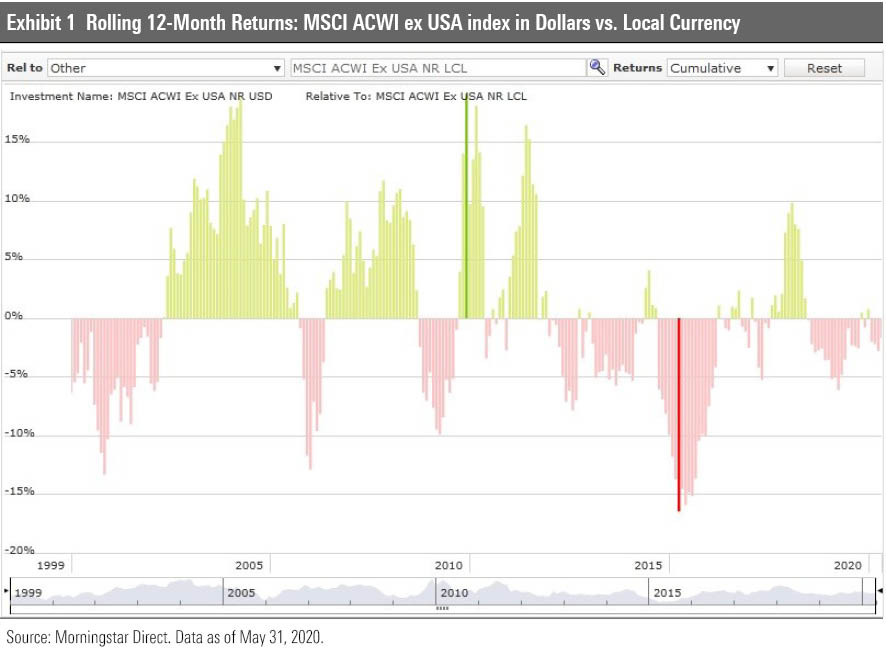

Background Currency movements can significantly impact the returns for investments based outside the U.S., like foreign stocks and bonds. To illustrate, the chart below compares the rolling 12-month returns of two well-known foreign-stock indexes, one of them translated back to the dollar (that is, unhedged) and the other in the local currency. As shown, these indexes have traded leadership through time, with the dollar-denominated index outperforming its local-currency counterpart when the dollar has been weak and vice versa when the greenback is strong.

Over the 10 years ended May 31, 2020, hedged portfolios have had an edge as the U.S. dollar has generally strengthened versus other major currencies. This has shaved nearly 1.6% per year off the return for the unhedged version of MSCI’s ACWI-ex US index compared with the hedged version of the same index.

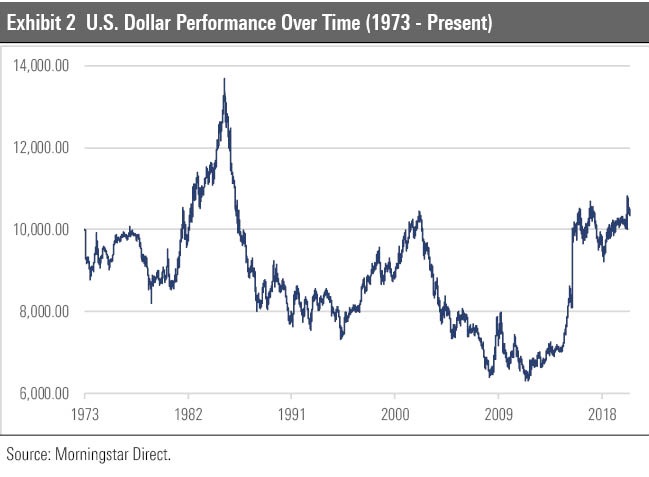

The Case for Hedging Currency Exposure in Foreign Stocks Given this, it probably seems tempting to hedge, but currency trends can cut both ways. The dollar went through extended periods of weakness between early 1973 and late 1978, early 1985 and early 1991, and mid-2001 until early 2008. If you held international funds during those periods, you would have been much better off in an unhedged vehicle.

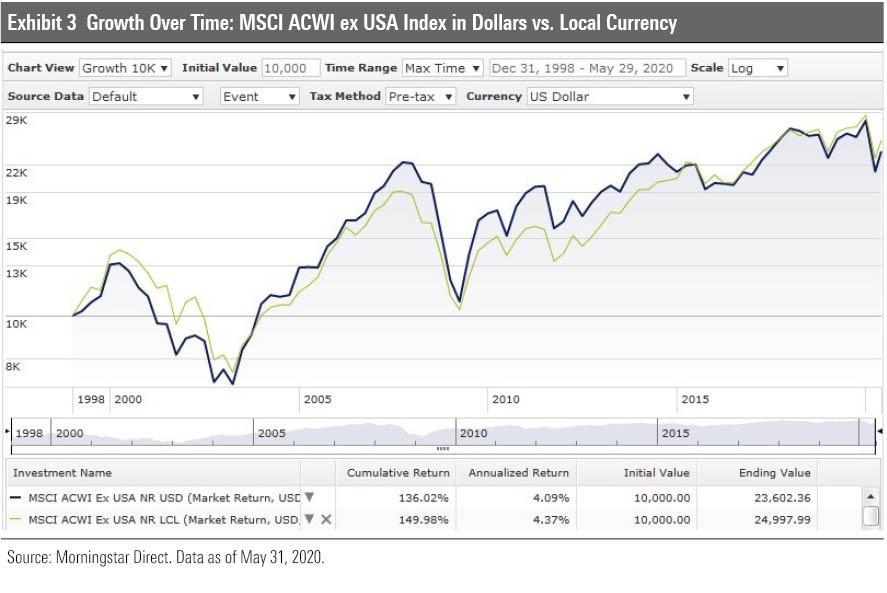

All told, the returns of the dollar-based and local-currency versions of these stock indexes haven’t been too different since inception. In other words, hedging wouldn’t have been a big help or a major hindrance over the long haul, as shown below.

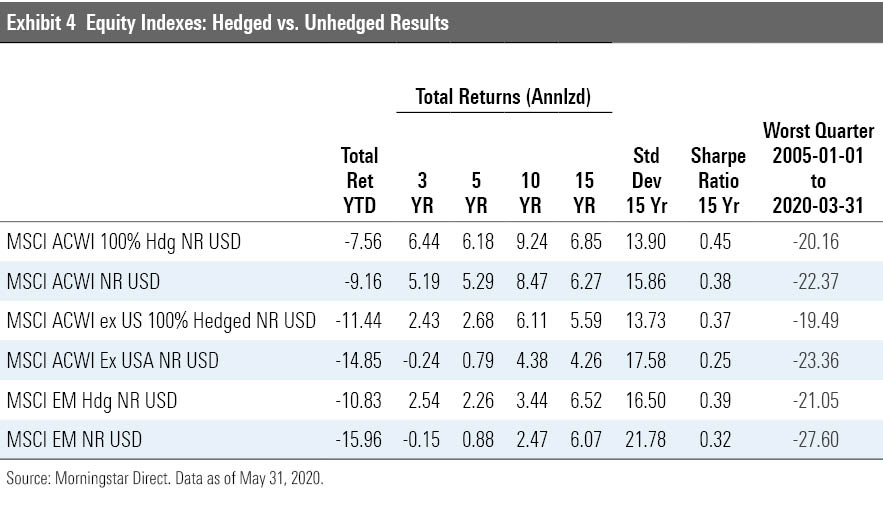

If hedging doesn’t boost returns, does it help put a damper on risk? As shown in the table below, the unhedged versions of major international indexes have tended to be more volatile than the hedged versions, reflecting the positive correlations of major currencies with each other. So, currency hedging has smoothed the ride a bit, producing better risk-adjusted returns.

But there are a few caveats. First, there's a cost to currency hedging. While that cost can vary based on different factors, a 2014 study found it can range from 1 to 18 basis points per year for developed-markets currencies. Second, currency-hedged strategies tend to be less tax-efficient than unhedged given the need to roll monthly forward contracts or other hedging instruments, which can lead to taxable capital gains. A pair of index-tracking exchange-traded funds from iShares, iShares Currency Hedged MSCI EAFE ETF HEFA and iShares MSCI EAFE ETF EFA, with the same portfolios but different hedging policies is a case in point. The hedged version has made numerous capital gains distributions since inception, while its unhedged counterpart has made none. As a result, the hedged version has an annualized five-year tax-cost ratio of 1.09%, compared with 0.70% for the unhedged edition.

Taken together, these factors argue for leaving foreign-stock exposure unhedged, though investors who are less risk-tolerant might consider hedging given the way it can take some of the edge off.

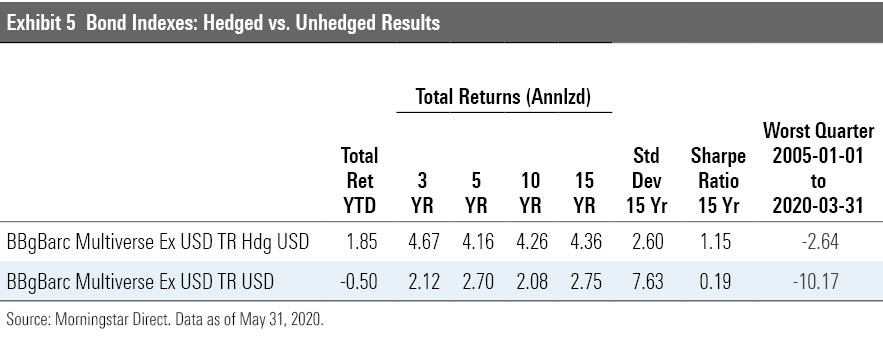

The Case for Hedging Foreign Bonds There's a much stronger case for hedging currency in non-dollar-denominated foreign bonds. Why? While unhedged foreign bonds have some diversification benefits, the volatility stemming from currency movements can swamp that of the bonds themselves. This is important given bonds' traditional role as portfolio stabilizers--that is, to offset the volatility from the equity portion of a portfolio. To illustrate, the table below compares the returns, volatility, and risk-adjusted performance of the hedged and unhedged versions of the Bloomberg Barclays Multiverse Ex USD Index. The unhedged index has been nearly twice as volatile as the hedged version.

What’s more, unhedged foreign-currency denominated bonds are much more prone to sell-offs. In comparing the worst quarterly losses of the hedged and unhedged versions of a widely known foreign bond index, we find that the unhedged index suffered losses that were nearly 4 times deeper than the hedged indexes. What this means, practically speaking, is that unhedged bonds can fail you when you need them most--amid market tumult when bonds are normally prized for their stability.

Finally, if you live in the United States, chances are most of your expenses are denominated in U.S. dollars. Keeping foreign bond assets unhedged adds some risk that assets you may need to cover expenses over the next several years could end up being worth less when translated back into U.S. dollars. This is also a risk for non-U.S. equity exposure, but most investors have a longer time horizon for their equity holdings, giving them more time to recover from any adverse currency movements. By contrast, fixed income is often earmarked for nearer-term goals and outlays, making stability even more important. This argues for hedging back any foreign-currency-denominated bonds into the dollar.

All told, the case for currency hedging is far stronger in fixed income than equity. If you are allocating a portion of your bond exposure to foreign bonds, strongly consider hedging it back to the dollar.

It's easy to get caught up in all the short-term noise about currency movements. There's also a danger of being overly swayed by performance over the past 10 years, which might suggest that currency hedging will always pay off. Over longer periods, though, currency movements tend to eventually cancel each other out. That means investors may want to consider leaving their non-U.S. equity exposure unhedged. At the same time, all but the most risk-tolerant investors are probably better off with hedged currency exposure on the fixed-income side.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_ffc6e675543a4913a5312be02f5c571a_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PKH6NPHLCRBR5DT2RWCY2VOCEQ.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/54RIEB5NTVG73FNGCTH6TGQMWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)