The Pandemic's Impact on Social Security and Medicare

Contributor Mark Miller examines the health of these critical programs in the face of the COVID-19 crisis.

Editor’s note: Read the latest on how the coronavirus is rattling the markets and what investors can do to navigate it.

When it comes to the financial health of retired Americans, nothing is more important than Social Security and Medicare--hands down.

The programs are nearly universal among senior citizens: Last year 64 million Americans received Social Security benefits and 62 million were on Medicare.

Without Social Security benefits, about four in 10 Americans aged 65 and older would have incomes below the poverty line; for about half of seniors, Social Security provides at least 50% of their income. And Medicare is the only health insurance game in town for seniors.

But how is the financial health of these critical social insurance programs holding up during the pandemic--and how will they fare after the emergency recedes?

The trustees of Social Security and Medicare issued their annual reports in April, and there wasn't much change to the long-range financial health of either program. The coronavirus pandemic's financial effects won't begin to show up until the 2021 report--and even then, no immediate "emergency" will have come into view. These programs are like mammoth battleships that take a very long time to turn, speed up, or slow down. In that sense, Social Security and Medicare play a stabilizing role for retirement at a time when almost everything else--incomes, portfolios, and the housing market—is up for grabs.

However, the pandemic will impact the financial health of both programs. Let's consider what we know now, and what might develop in 2021 and beyond.

Social Security Social Security's financial forecast has been pointing toward a long-range shortfall for many years. This year's report showed no change--the combined trust funds for the retirement and disability programs are on course to be depleted in 2035; without reforms, funding from payroll tax receipts will be sufficient at that point to pay just 79% of scheduled benefits.

The projected shortfall stems primarily from the retirement of baby boomers combined with the slow growth of the labor force, which reduces the ratio of workers paying into the system to beneficiaries. Rising life expectancy also plays a role; so does rising inequality in worker earnings.

Those factors are driving a drawdown of the massive trust fund, currently pegged at about $2.9 trillion.

The odds that Congress would allow an across-the-board benefit cut of 20% or more seem small to none, in my view--and lawmakers have many paths available to fix the problems. All involve increases in revenue, cuts to benefits, or some combination of both.

Social Security is funded primarily by a 12.4% payroll tax, split between employers and workers (the program also receives some funding from income taxes collected on benefits of higher-income recipients and from interest on trust fund bonds). Higher payroll tax rates could close some of the gap; other options include new sources of tax revenue, higher retirement ages, less generous cost-of-living increases, or benefit reductions for high income seniors ("means testing," as some call it).

The pandemic could accelerate the 2035 exhaustion date. This would not be driven by an acceleration of early benefit claims owing to job loss among older workers. While that's likely, an increase in claims wouldn't affect the program's finances one way or the other--the program's flexible claiming age structure is designed to keep lifetime benefits constant for an individual with average life expectancy. The formula uses actuarial assumptions that determine the percentage reductions in monthly benefits for those who claim before full retirement age (currently, a little over age 66) and delayed claiming credits for those who wait.

The main cause of concern will be declining payroll tax receipts owing to the depressed economy and lower employment levels.

The outlook for the economy is the key driver here, and that outlook is highly uncertain right now. No one can tell you how long shutdowns will last or how long the economic pain will persist after the worst of the pandemic crisis passes.

The outlook for small businesses is especially frightening. A new study by a group of economists found that more than 100,000 small businesses--2% of the total--have shut permanently since the pandemic escalated in March, and one forecast predicts more than 1 million small business failures as a result of the crisis.

How might this impact Social Security? Again--remember it's like a battleship. Stephen Goss, Social Security's chief actuary, discussed the outlook last month during a webinar convened by the Bipartisan Policy Center. He stated that a reduction in employment earnings and payroll taxes of 15% for the entire year would change the depletion date from early 2035 to the middle of 2034. If a decline on that order continues for a second year, the depletion date would move up to middle or late 2033.

“Unless we have a really expansive period with deep, permanent reductions, we're expecting we might have a reserve depletion date one or two years earlier for the trust funds,” he said. “But all bets are off, and we will just have to see what happens, because we really don’t know whether we’ll be back to normal,” he added.

Indeed, if the recession is more prolonged, the exhaustion date could get closer. BPC forecasts that the combined retirement and disability trust fund reserves could be depleted as early as 2029 in the event of a longer recession.

Whenever policymakers get around to addressing the shortfall, they should consider an important long-range question: How big of a role should Social Security play in providing retirement security to Americans? Before the pandemic, the oft-discussed three-legged stool of retirement--Social Security, pensions, and savings--was looking rather wobbly. Traditional pensions have been shrinking for years in the private sector, and only about half of households owned retirement saving accounts.

The pandemic will ravage retirement savings. Many employers are suspending 401(k) contributions and the CARES Act provides very flexible account drawdown options for workers affected by coronavirus. If this massive wave of small business failures comes to pass, one side effect will be retirement plan terminations. Some experts think one in five plans will terminate (when that occurs, participants can either roll over their accounts into IRAs or take cash distributions).

All of that will underscore the need to not only to avoid slashing Social Security benefits in 2035, but to expand benefits.

Medicare Medicare's funding is not limited to payroll taxes. The program's largest source is general federal revenue (43%), followed by payroll taxes (36%) and beneficiary premiums (15%), according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Here’s how this breaks out, according to KFF:

- Part A (hospitalization) is financed mainly through a 2.9% payroll tax split by employers and employees. (Higher-income taxpayers also pay a higher payroll tax on earnings of 2.35%.)

- Part B (outpatient services) is funded through general revenue (72%), beneficiary premiums (26%), and interest on trust fund assets.

- Part D (prescription drugs) is financed by general revenues (71%), beneficiary premiums (17%), and state payments for beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (12%).

- High-income beneficiaries pay income-related monthly adjustment amounts, or IRMAA.

The Hospital Insurance trust fund was not in great shape before the COVID-19 crisis began--it was forecast to be exhausted in 2026. The HI exhaustion date does bounce around from year to year, but experts agree that the 2026 forecast was a cause for major concern--exhaustion would mean Medicare would have sufficient revenue from incoming payroll taxes to meet only 90% of its expenses, according to the most recent Medicare trustees’ report.

The impact of COVID-19 on the HI trust fund’s outlook is uncertain. Spending on COVID-19 care is up sharply, of course. Congress has authorized additional emergency payments to hospitals during the crisis and has eliminated cost-sharing requirements for COVID-19 care. On the other hand, outlays for elective and other procedures have been lower during the initial months of the crisis. This spending likely will increase as the year unwinds, and there are initial signs that it already is trending upward.

On the revenue side, payroll tax receipts certainly will fall--but by how much and for how long is anyone’s guess.

Still, the HI trust fund’s condition is likely to worsen by the time the Medicare trustees issue their next report in 2021, says Tricia Neuman, director of the Medicare policy program at KFF.

“Could the date move up by one or two years? It’s hard to say right now, but with less money coming in it’s difficult to imagine that the insolvency date won’t get closer,” she says.

Meanwhile, the table could be set for a big jump in Part B premiums next year--but one that might only affect a portion of enrollees. That’s because we also may be headed for a zero cost-of-living adjustment for Social Security. Let’s unpack this.

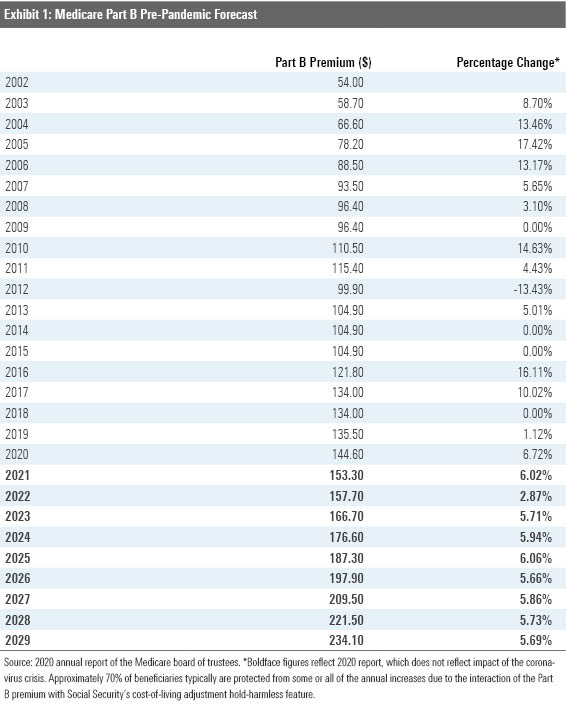

The Part B premium is equal to 25% of total program costs as forecast by Medicare’s actuaries. The Part B premium has jumped 38% since 2015, and further sharp escalation was predicted before the pandemic struck.

There is a great deal of uncertainty about what Part B outlays will look like next year. But outpatient healthcare utilization could surge due to coronavirus care and spending deferred from this year.

For anyone receiving Social Security, the Part B premium cannot increase by a greater percentage than the annual COLA. Right now, the virus-induced downturn is producing strong deflationary pressures--the consumer price index fell 0.8% in April, the largest single-month decline since 2008. If that keeps up, the COLA for 2021 would be zero--benefits would stay flat.

For Medicare enrollees who also receive Social Security and pay the standard premium--$144.60 this year--the so-called “hold harmless” provision in federal law would keep the Part B premium at that rate for 2020. They would be subject to larger “catch up” increases in later years.

Meanwhile several other groups of Medicare enrollees would be subject to a higher premium next year, including:

- Anyone who is on Medicare but has been delaying their filing for Social Security benefits.

- Anyone enrolling in Medicare for the first time next year.

- Federal retirees who participated solely in the older Civil Service Retirement System and therefore don't receive Social Security benefits.

- State government workers who participated in defined-benefit pension plans and are not covered by Social Security during their tenure as state employees.

- Low-income "dual-eligible" seniors who receive Social Security and also participate in both Medicare and state-run Medicaid programs. Their premiums are absorbed by state Medicaid budgets.

- Higher-income beneficiaries already subject to IRMAA would be hit with big increases.

How about Part D prescription drug coverage? The virus is not expected to have much impact on this program, at least in the near term. Any vaccine will be covered under Part B. enrollees likely are ordering extended supplies of routine medications covered under Part D, but that will only accelerate some spending into this calendar year that would have occurred later.

Mark Miller is a journalist and author who writes about trends in retirement and aging. He is a columnist for Reuters and also contributes to WealthManagement.com and the AARP magazine. He publishes a weekly newsletter on news and trends in the field at Retirement Revised. The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)