Why You Should Still Care About Inflation

It hasn’t been much of an issue lately, but it’s still a long-term threat.

Editor’s note: Read the latest on how the coronavirus is rattling the markets and what investors can do to navigate it.

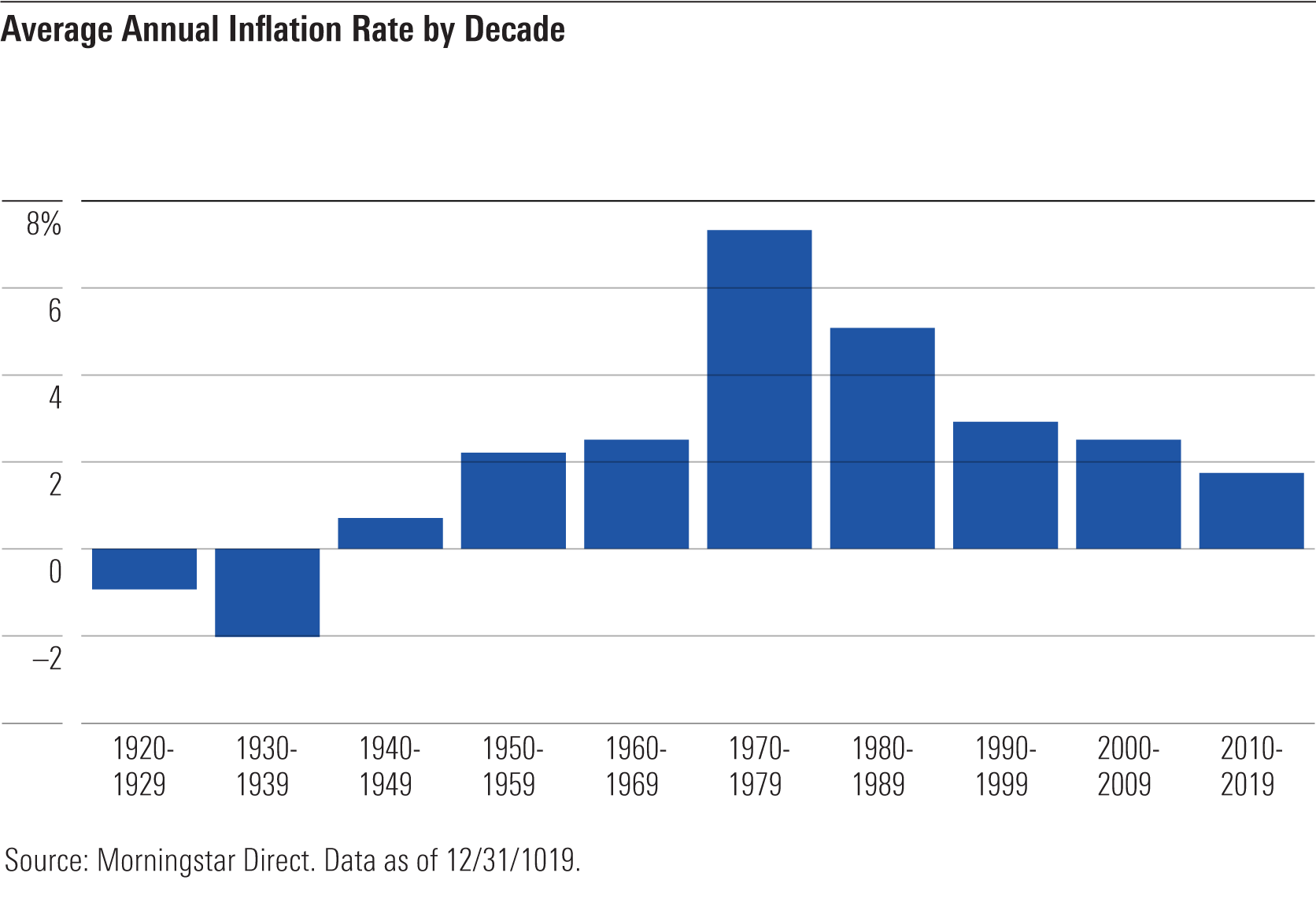

It’s fair to say that inflation has been pretty much a nonissue for a long time. I have vivid memories of hearing dire warnings about rising energy prices during my childhood in the 1970s, but since then, inflation has been in a secular decline. In fact, average inflation rates by decade have gradually stepped down, from 7.4% in the 1970s, to 5.1% in the 1980s, to 2.9% in the 1990s, to 2.5% in the 2000s, and just 1.8% in the past 10 years.

The sudden economic disruption from the novel coronavirus has brought inflation even lower. With the sudden spike in unemployment, rapidly dropping oil prices, and business demand grinding to a halt, monthly inflation actually declined in April 2020 from March levels based on the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Much of the decline was driven by declining energy prices, along with lower prices for economically sensitive areas such as apparel, travel, and consumer hardware.

There are reasons to believe this trend might continue. For one, the Federal Reserve has an explicit inflation target of 2%, which it officially established in 2012. The Fed uses inflation forecasts relative to this target, along with other economic data, as part of its decision framework for making changes to short-term interest rates.

Near-term economic weakness is another factor that would likely keep inflation in check. By definition, a fall-off in consumer demand helps drive prices lower, leading to either deflation (an inflation rate below zero) or disinflation (a reduction in the rate of inflation). During previous recessions and depressions, inflation has often (though not always) declined or dropped below zero. The Great Depression from 1929 through 1939 is a case in point. Over this period, consumer prices (as measured by the BLS CPI All-Urban NSA Index) dropped by about 1.8% per year. The postwar recession from 1920 to 1921 is an even more extreme example. In the wake of World War I and the 1918 flu pandemic, industrial production and employment both plummeted. At the same time, consumer prices fell at a double-digit rate in 1921, with wholesale prices dropping even further.

The economic aftershocks of the coronavirus pandemic are largely unknown, but most experts expect sharp economic declines in the second quarter of 2020 followed by some sort of recovery by the end of 2021. Even after lockdown restrictions are relaxed, nonessential business openings and consumer spending could remain depressed for an extended period of time, particularly if a resurgence in COVID-19 infections leads to periodic reclosings and tighter restrictions on movement and activity.

While the overall economic environment probably points to inflation remaining low, there are still pockets of inflation here and there. Supply-chain disruptions and plant closures following COVID-19 infections at processing plants have driven up prices for meat and other groceries. Based on the Labor Department’s recent release, the price of meats, poultry, fish, and eggs rose 4.3% in April, while grocery prices were up 2.6% overall. Costs for healthcare and long-term care have also been trending at a higher rate in recent years. That’s particularly worrisome for seniors, who often face multiple health issues requiring additional care during the last years of life.

Moreover, the aggressive stimulus package may eventually lead to higher inflation. The government stimulus package has already totaled $2.2 trillion, and Congress will likely expand that amount in the coming months. At the same time, the Federal Reserve has been aggressively purchasing bonds and reducing interest rates. The government printing more money is basically a textbook cause of higher inflation because it decreases currency values.

Granted, many market observers predicted higher inflation rates in the wake of aggressive fiscal and monetary stimulus in 2008, but that didn’t really materialize. However, the scale of spending is much higher this time around. In addition, it’s possible that supply/demand imbalances could lead to higher inflation if a resurgence in consumer demand coincides with supply disruptions and depressed levels of production in the wake of wide-scale economic shutdowns.

Because we ultimately don’t know how inflation will shake out, it’s prudent to carve out a portion of your portfolio to guard against different scenarios. In periods of deflation or disinflation, cash and Treasury bonds typically perform well.

On the flip side, Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities are the most straightforward way to protect against a potential increase in inflation. TIPS guard against inflation in two ways. First, their principal value is tied to changes in inflation. Second, their coupon payments are also adjusted based on changes in the principal value. In periods of higher inflation, TIPS pay out more interest and also increase in par value. At maturity, the U.S. government will pay back either the adjusted par value or the original principal, whichever is higher.

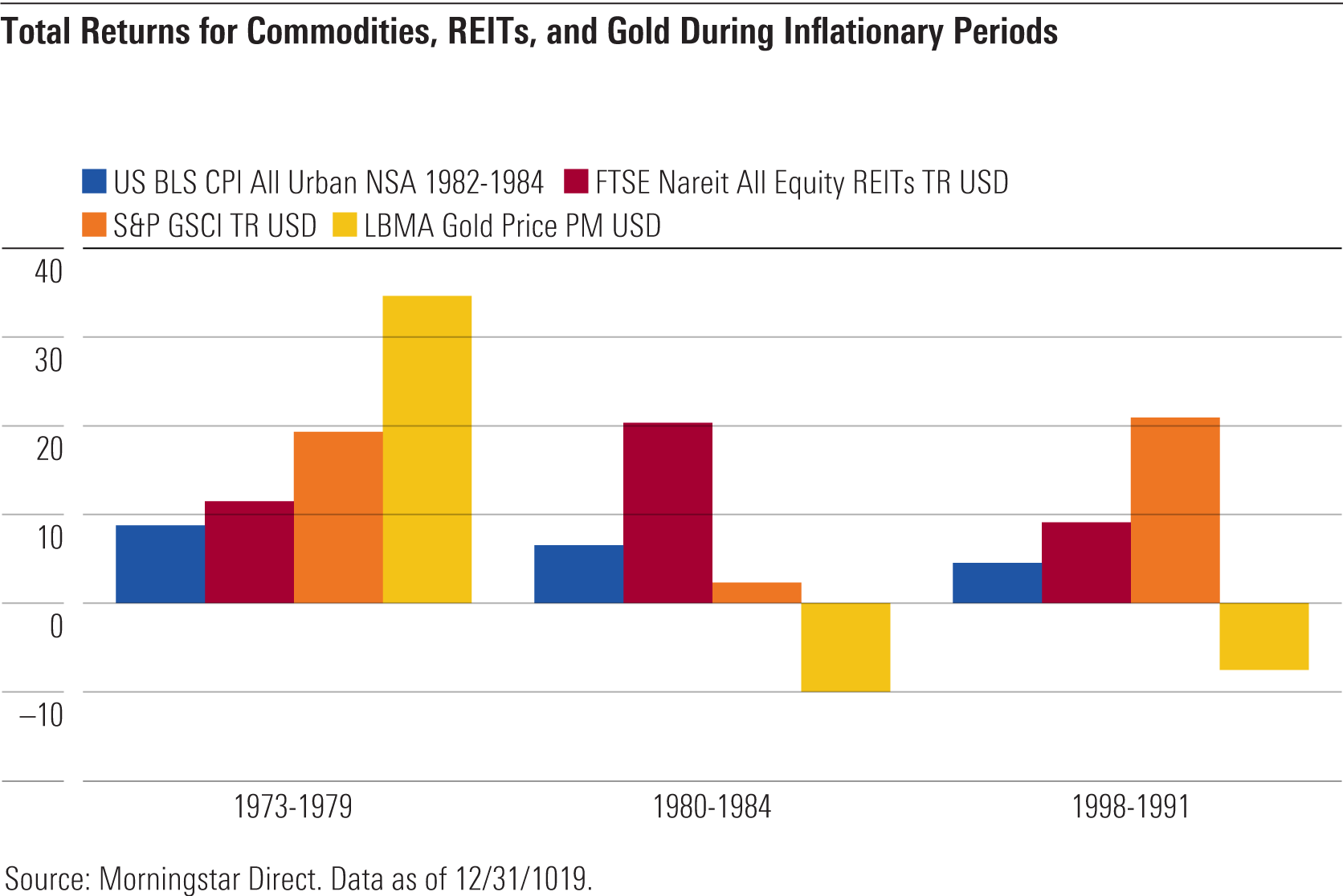

It’s tough to get a handle on other asset classes to use as an inflation hedge simply because we haven’t seen periods of high inflation in recent history. But looking back on some previous inflationary periods helps shed some light on which asset classes have performed best as inflation hedges.

As shown below, commodities have the most consistent record as inflation hedges. This makes sense, because the Consumer Price Index is partly based on commodity prices. Of the three asset classes we looked at, only commodities showed a significantly positive correlation with inflation. All else being equal, that suggests that commodity prices tend to move in the same direction as inflation (although not always to the same degree).

REITs have also fared relatively well. Because property owners have historically been able to pass along most increases in their underlying costs to tenants by raising lease prices, real estate boasts a built-in inflation hedge. It can also benefit from greater demand during periods when surging economic growth leads to higher inflation. (It’s not clear whether this will remain the case going forward if the pandemic prompts companies to adopt more-permanent work-from-home policies, though.)

Gold is often touted as an inflation hedge, but it actually has a pretty low correlation with inflation. Its performance record is decidedly mixed: In some years with higher inflation, it has shot the lights out, but in other years, it’s been a dud.

From a portfolio construction perspective, it's worth carving out a small portion of a portfolio for assets that can help counter inflation. Of the three asset classes shown above, commodities probably have the strongest case as an inflation hedge. However, commodities have also shown the highest levels of volatility (as measured by standard deviation) among the three and have also been subject to large drawdowns. In fact, previous academic research has found that adding commodities to a diversified portfolio can improve risk-adjusted returns over time, but that pattern has not played out in recent history. Therefore, adding commodities to a portfolio as an inflation hedge requires a bit of a leap of faith as well as a tolerance for risk.

A less risky way to guard against inflation risk is by increasing a portfolio’s equity exposure. It’s important to note that stocks aren’t really a direct hedge against inflation. In fact, the correlation of broad equity market benchmarks with inflation is close to zero. Instead, stocks can help offset the erosion of purchasing power from inflation simply because they generally offer better long-term returns than other asset classes. Because of this, their real returns (nominal returns minus inflation) should be higher than those of other asset classes over longer time periods.

On the fixed-income side, in addition to buying TIPS, investors might also want to tweak their other fixed-income holdings. By staying toward the shorter end of the maturity spectrum, investors can guard against the inflation risk inherent in longer-term bonds, particularly now that interest rates are at a historic low.

Conclusion It's become commonplace to observe that we live in unprecedented times. That may be true, but it's also worth looking back over history to find events that could eventually be repeated. As Larry Siegel has pointed out (as aptly described by my Morningstar Canada colleague Paul Kaplan), unique negative events, or "black swans," are really better described as "black turkeys"---events that can be readily observed from historical market data but that investors tend to ignore in favor of more rosy scenarios.

When it comes to inflation, it would be easy to get lulled into a sense of complacency by looking at recent history. Taking a longer-term view, though, it’s worth considering the possibility that inflation could eventually return to less benign levels. If that happens, portfolio diversification should once again prove its merits.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HTLB322SBJCLTLWYSDCTESUQZI.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/TAIQTNFTKRDL7JUP4N4CX7SDKI.png)