What the Economic Downturn Could Mean for Pension Plans

Contributor Mark Miller explores the health of corporate, multiemployer, and public plans.

Editor's note: Read the latest on how the coronavirus is rattling the markets and what investors can do to navigate it.

Investing guru Bill Bernstein has compared investors in defined-contribution plans to airline passengers sent to the cockpit to fly the plane. Bernstein would much prefer a retirement system that relies on defined-benefit pensions, with their professional management and automatic participation.

The unfolding coronavirus crisis underscores the value of professional pension pilots--and the structure of defined-benefit plans, which don't rely on short-term market performance to meet near-term obligations. The same claim cannot be made for the 401(k) or IRA accounts of investors who are retired or close to retirement. Such investors are facing tough questions now about the reliability of their portfolios.

While there's no immediate danger that defined-benefit pension plans will fall short of resources to meet obligations during the pandemic crisis, many are taking their lumps as financial markets tumble. And the knock-on effects of the economic downturn could pose long-term challenges for pension plan sponsors as they try to meet their obligations to participants.

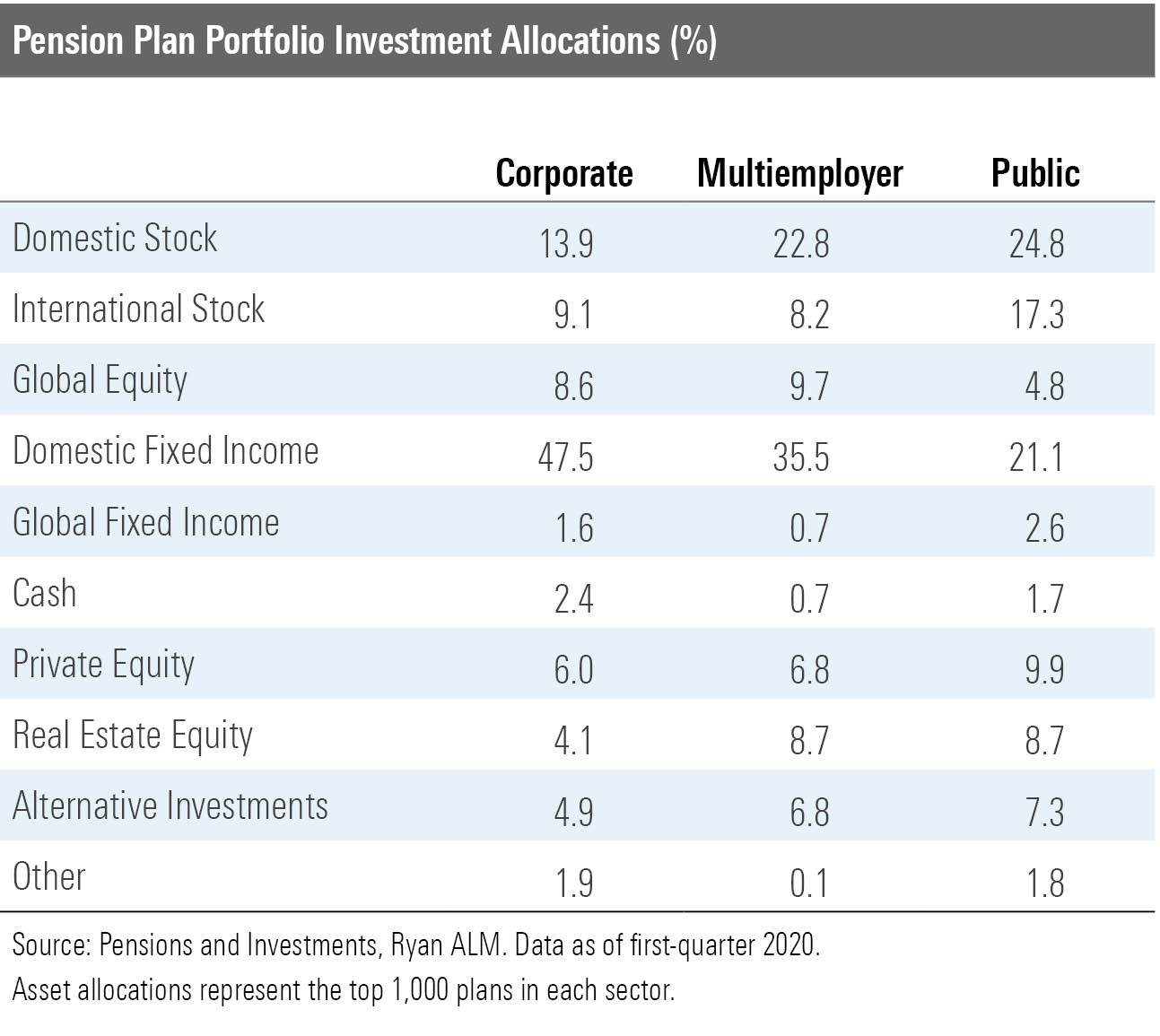

The situations vary among the key pension sectors--corporate, multiemployer, and public.

Corporate Pension Plans Many employers have shifted their retirement plans from defined-benefit to defined-contribution models. In 1998, 238 of the companies among today's Fortune 500 offered a defined-benefit plan to new workers, compared with just 16 now, according to Willis Towers Watson. But that still leaves plenty of workers with access to a pension benefit--and once promised, sponsors must meet those pension obligations.

"It's true that sometimes benefits have changed over time, or they've been closed to new entrants," says Royce Kosoff, managing director of retirement at Willis Towers Watson. "But sponsors cannot go in and cut back benefits that have been accrued in the past, so there are a lot of protections. The drop in investment value is a challenge for sponsors, but it's not like a 401(k), where it's 100% on the participant without a backstop."

Tumbling equity markets took a bite out of large corporate plans during the first quarter of 2020; these plans' funded status (that is, assets available to meet promised benefit obligations) fell by about 8%, the firm reports.

But corporate plans have been required to boost their funded ratios in recent years, and that puts them in a strong position to withstand the current financial market storms. The Pension Protection Act of 2006 required that they maintain a funded status of 80%.

Pension funding reforms over the past decade have allowed sponsors to use slightly higher interest rates to measure future obligations and a 25-year smoothing of rates, which has buffered the impact of falling rates. As a result, most sponsors were at or above the 80% funding level when they reported earlier this year. But the number could decline when they next report in January 2021, Kosoff thinks.

"It's going to depend on how the rest of 2020 plays out in the markets," he says. "But even with lower funding levels, there are significant asset pools backing up these benefits--they're invested for the long term."

Participants in corporate plans also have a backstop. If a plan runs into financial problems and terminates, most participants will be fully protected by the federal government's pension insurance program, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation. The PBGC's single-employer guarantee fund is in good financial health.

Another uncertainty for corporate pensions is the recent trend toward plan "derisking," that is, plans that offer lump-sum buyouts to retirees and former workers or transfer their obligations to private insurance companies.

If plan funding levels drop significantly, derisking deals will become more expensive for sponsors.

"It's too early to tell whether or how that market will be affected," says Kosoff.

But if the derisking trend continues, more pension beneficiaries can expect to receive lump-sum buyout offers.

Multiemployer Pension Plans Roughly 10.6 million workers and retirees are relying on pensions from so-called multiemployer plans. These plans are created under collective bargaining agreements and jointly funded by groups of employers in industries like construction, trucking, mining, and food retailing. There are about 1,400 multiemployer pension plans today.

Before the virus crisis, multiemployer plans covering 1.3 million workers and retirees were considered badly underfunded. To address the problem, in July 2019 the House of Representatives passed legislation built around providing low-interest loans to struggling plans. Democrats have tried to get this solution incorporated into virus-related bailout legislation, and its cost ($49 billion) is really small change in the context of the trillions streaming out of Washington right now.

Along with assuring safe retirement for millions of retirees of modest means who were promised these benefits, saving the multiemployer funds would provide an economic shot in the arm for struggling communities across the Rust Belt, where many of these workers live.

But so far, Democrats have not been successful.

Time is short. The Teamsters' Central States Pension Fund had more than $26 billion in unfunded pension obligations before the virus crisis, and it is projected to fail in 2025. That would exhaust the PBGC multiemployer fund.

Russ Kamp of Ryan ALM, a fixed-income firm specializing in liability management, notes that 125 plans were in critical condition before the crisis struck, and he estimates that number will grow to about 200.

A true assessment of the problem won't come into view until early next year, says Gene Kalwarski, CEO of Cheiron, an actuarial consulting firm.

"We're in the middle of a storm right now, and we won't really know how this looks until it passes," he says.

State and Local Government Pension Plans Like the corporate and multiemployer sectors, public pension plans are a critical linchpin of retirement security in the United States, and they are important economic stabilizers as a source of income in communities across the country. Public plans hold about $4 trillion in assets for 20 million active and retired public sector employees, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, or CRR.

At an aggregate level, the funded status of public plans declined steadily from 2001 to 2011 because of two market downturns during that period but has held steady since 2012, CRR reports. Plans were more than 100% funded in 2000, but that funding rate dropped to 86% in 2007 and stood at just 73% in 2018.

Many plans took on more risky investments, including stocks, private equities, hedge funds, and commodities, according to Kamp.

"Corporate plans have been reducing risk while others are trying to generate return," observes Kamp.

Moody's Investors Service has estimated that state and local pension funds lost $1 trillion in this year's market decline.

"Public pension plans are going to be hurt, just like all other plans, be they defined-benefit or defined-contribution," says Alicia Munnell, CRR's director. "When this crisis is over and we all take stock, we're going to see plans much less well-funded than they were before--and among the worst funded, a couple of them might be facing exhaustion of their assets within a couple/few years."

Munnell says that people should still expect to see their benefits.

"Our sense is that for the foreseeable future, plans can muddle through," she adds.

Pressure on government budgets will pose a major part of this challenge as states and municipalities face tough decisions about where to allocate dollars. Soaring costs related to fighting the pandemic are part of this picture, along with falling tax revenue.

"States and localities are going to use all the resources they can to deal with the virus," Munnell says. "So, it's going to be really difficult to find the money to make pension plan contributions. It's a terrible event and it's going to be hard on taxpayers as well."

It's important to be cautious about predicting the future health of poorly funded plans at this point, considering the highly uncertain outlook for the economy and financial markets.

"There's a lot we don't know at this point," says Jean-Pierre Aubry, associate director of state and local research at CRR. "The markets may bounce back, and we don't know yet what the policy responses will be. In the past, when struggling plans have faced this situation, they often come up with the money ahead of their exhaustion dates. And some make changes or cuts in benefits."

Unlike corporate pensions, public sector plans are not protected by the PBGC. If you want to look up funded status on specific plans, CRR maintains a database.

Mark Miller is a journalist and author who writes about trends in retirement and aging. He is a columnist for Reuters and also contributes to WealthManagement.com and the AARP magazine. He publishes a weekly newsletter on news and trends in the field at Retirement Revised. The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MFL6LHZXFVFYFOAVQBMECBG6RM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HCVXKY35QNVZ4AHAWI2N4JWONA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EGA35LGTJFBVTDK3OCMQCHW7XQ.png)