Bogle Had a Point on International Stocks

Vanguard's founder didn't see the need for them, and the markets haven't shown reason to suggest he was wrong.

Testing the Numbers Infamously, Vanguard Founder Jack Bogle saw no reason to own foreign stocks. That stance made him an outlier at best and a crank at worst. What's more, Vanguard offered several international-equity funds, which put Bogle in the awkward position of contending that because he didn't believe in such funds didn't mean that Vanguard shouldn't offer them, as its customers might hold different views. So much for investment managers "eating their own cooking."

Any idiot can argue from history by looking backwards for numbers to support a thesis. The impressive part is that Bogle made that argument decades ago, and the financial markets haven't offered even a whiff of a suggestion that he might have been wrong. In chess terminology, the opponent has had no counterplay.

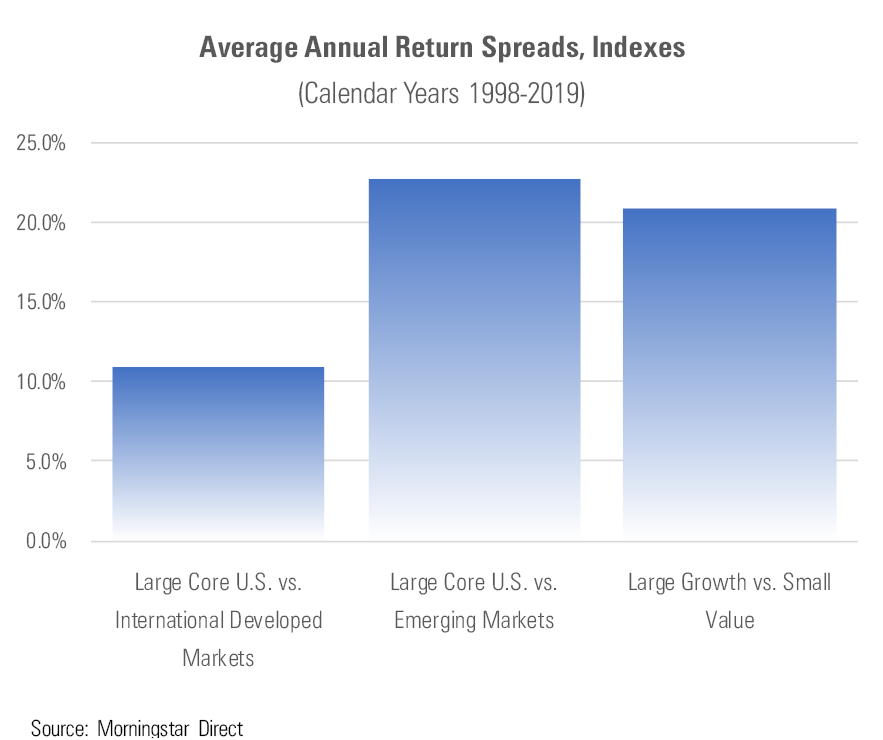

To support that statement, I looked at the difference in calendar-year returns between various indexes. The intuition is simple: If the indexes perform similarly, so that only a few percentage points separate their results, then splitting an investment among them doesn’t provide much diversification benefit. The investors could just as well pick one of those assets and skip the other.

I selected three pairs of equity indexes: 1) large-company U.S. versus large-company foreign, 2) large-company U.S. versus emerging markets, and 3) large-growth U.S. versus small-value U.S. (The four U.S. indexes are provided by Morningstar. For their part, large-company foreign is represented by the MSCI All Country World Index ex USA benchmark, while emerging markets is captured by the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.)

The first pair illustrates the conventional approach to international investing; the second depicts when emerging-market equities are substituted for those from developed markets; and the third shows the strongest version of domestic-equity diversification, as the large-growth/small-value diagonal features the biggest performance disparities. The time period begins in 1998, that being the inception year for Morningstar’s equity indexes. The bars represent calendar-year averages.

A Blue Chip Is a Blue Chip That emerging-markets stocks behaved less like U.S. equities than did developed-markets stocks comes as no shock. Blue chips trade similarly, no matter where they are headquartered, and the major economies almost always move together. It is highly unlikely that, say, German stocks would plunge while American equities surge. In contrast, the emerging markets have often followed their own cycle.

What may surprise, though, is that diversifying across two U.S. investment styles provided double the diversification punch of the conventional form of international investing. Indeed, the effect almost matched that from buying emerging-markets equities. Large-growth and small-value companies may reside within the same country, but they clearly respond to divergent causes.

This finding, to be sure, is exacerbated by the choice of the time period, as Morningstar’s equity indexes were launched at the height of the New Era. The performance gap between large growth and small value was therefore initially huge, before subsiding. However, it then sprang back to life. The U.S. style performance difference exceeded that for international investing in 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, and so far again in 2020. That would seem to be a trend.

The performance difference from large-growth/small-value investing during those years has also exceed that of U.S. stocks versus emerging markets. That result doesn’t strike me as repeatable. Although the emerging markets are gradually becoming more intertwined with the global economy, thereby reducing their diversification benefits, one suspects that they do not yet move in lock step.

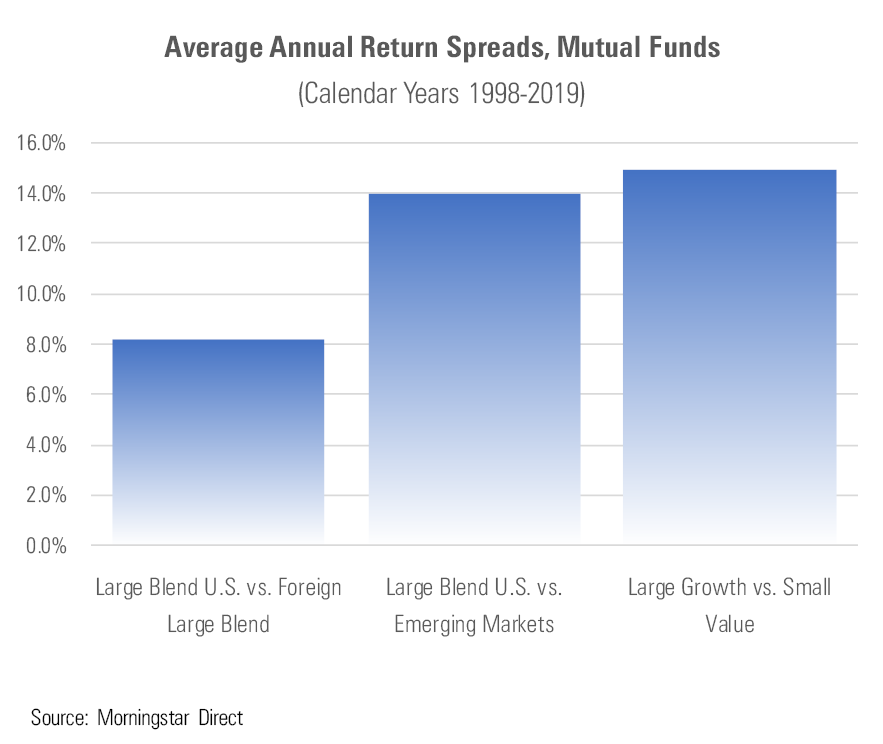

Now, Mutual Funds Index simulations are directly relevant for exchange-traded fund investors, but they can be misleading for those who possess active mutual funds. Indexes are constructed for purity; in contrast, even active funds that carry specific names, such as "mid-cap growth," typically invest substantially in securities that don't match their labels. Such practices dilute the diversification benefits that come from investing across asset classes.

Therefore, I took a second look at the issue, substituting category averages from mutual funds for stock-index returns. I retained the same time period and investment pairings. The categories were 1) U.S. large-blend stock, 2) foreign large-blend stock, 3) diversified emerging markets, 4) U.S. large-growth stock, and 5) U.S. small-value stock.

A similar pattern, but at a reduced level. The performance differences from diversifying into emerging markets stocks or across the two U.S. styles shrunk from 20-plus percentage points to about 14. The gap that came from traditional international investing also declined, to 8 percentage points. That is not very much! Not since 2014 has the annual performance difference between large-blend U.S. funds and large-blend foreign funds reached double digits.

Perhaps a more direct way of making the point: Counting 2020, blue-chip U.S.-stock funds have lost money in five calendar years since 2002. On each occasion, foreign large-blend mutual funds not only also finished in the red, but they fell even further than did their American cousins. As insurance policies go, I have seen better. Whenever U.S. equity-fund shareholders have needed the protection, their international funds have worsened their problems, not fixed them.

Performance, Not Diversification The past, of course, will not necessarily repeat. Indeed, it would be strange if U.S. stocks continued to beat their overseas equivalents during every down market. One of these days, holding European and Japanese equities during a stock-market slide will make American investors relatively happy. It's doubtful, though, that the typical international fund will ever provide a significant diversification benefit.

This column doesn’t invalidate the practice of international investing. Perhaps international stocks will post higher gains. It could well be that U.S. stocks will trail their foreign counterparts over the ensuing decade, just as they surpassed international equities over the previous one. Also, there are many flavors of international funds, as well as hundreds of active managers, some pursuing highly idiosyncratic strategies. There are always opportunities for outperformance.

But outperformance is not diversification. It is difficult to justify owning international stocks “just because.”

Second Worst To say that I have been baffled by the S&P 500's rally is an understatement. It's one thing for stocks to rebound during a bear market. It's quite another for them to almost immediately gain a whopping 25%. Neither can I square the economic consensus of a powerful third-quarter rebound with medical forecasts that suggest the United States will spend the rest of 2020 observing at least some forms of social distancing.

However, there are people even more confused than I am: those poor souls whose jobs require them to explain daily stock-market returns. This Monday, we were told, the S&P 500 rose 7% because investors were relieved that the New York death toll had declined the day before. The death toll promptly rose over the next two days and … the S&P 500 continued its rally.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZM7IGM4RQNFBVBVUJJ55EKHZOU.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_d910b80e854840d1a85bd7c01c1e0aed_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/K36BSDXY2RAXNMH6G5XT7YIXMU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)