A Closer Look at the New Ratings Process for Index Funds

The new ratings framework should improve ratings efficacy by bringing more structure and consistency to the ratings process and elevating the impact of fees.

A version of this article previously appeared in the November 2019 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Click here to download a copy.

Morningstar recently made some significant changes to the methodology behind the Morningstar Analyst Rating to build on the strengths of the old system and improve ratings efficacy. The new methodology is effective for all funds rated on or after Nov. 1, 2019. Here is a closer look at the changes and what they mean for the rated universe of index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds.

Analyst ratings are designed to help steer investors toward funds that are likely to provide better risk-adjusted performance than a relevant benchmark or peer group over the long term. Historically, they rested on five pillars: qualitative assessments of a strategy's process, people, parent, performance, and price. The new ratings framework leverages much of the same research, but it brings more structure to the ratings process. It also raises the bar for active strategies and more directly accounts for fees.

How Target-Rich Is the Opportunity Set? The new ratings framework starts by estimating the potential range of performance that funds in each category can generate. Some Morningstar Categories are more target-rich than others. For example, managers in the short government-bond category have less room to differentiate themselves than managers in the emerging-markets local-currency bond category. While this was a consideration in the original ratings framework, the new framework measures it more systematically.

In this step, Morningstar estimates the value that funds in each category have historically delivered. This is based on rolling three-year regressions, going back to 2000 (where data are available), of each fund's gross-of-fees performance relative to its category index. This provides alpha estimates, which measure each fund's performance relative to the benchmark after adjusting for differences in risk.

The model uses the width of the distribution of these alphas to determine the richness of the opportunity set rather than their absolute magnitude. That's important for a few reasons. 1) It prevents performance-chasing. On its own, past performance isn't a great predictor of future performance. It's more intellectually honest to assume that the average gross-of-fees alpha in each group is zero, as the average fund in most categories tends to look a lot like its category benchmark. 2) The distribution of alphas is more stable than their magnitude, which should lead to more-stable ratings. 3) It shows how big of an impact a fund's process, people, parent, and price can have on its peer-relative performance, which aligns with the next step in the ratings process.

If managers in a category invest similarly, the dispersion of performance will likely be tighter than if the category were more diverse. Similarly, as market competition increases, prices are more likely to be fair, which should make it more difficult to gain an edge and cause performance to cluster more tightly.

Within each category, there are two alpha distributions: one for active funds and one for passive funds. This is done because the dispersion of performance among index funds is usually much tighter than it is for active funds. Combining them would not be representative of the range of outcomes that index funds could deliver.

Passive funds aren't designed to deliver alpha in the traditional sense. They often look a lot like their category indexes and typically don't generate significant alphas against them. The category median is a better benchmark for these funds because it shows how well index investing works relative to the competition.

Strategic-beta funds are treated differently. These are included in the distribution of active funds because they are index funds that make active bets.

Three Pillars The estimates of the opportunity set size are combined with the analyst-assigned pillar scores to form an estimate of each fund's gross-of-fees alpha potential. The impact of the pillar scores is proportional to the size of the opportunity set.

In the new framework, there are three pillars instead of five, and they drive the gross-of-fees alpha estimates and require qualitative analyst input. They are Process, People, and Parent. Performance and Price are notably missing.

Past performance alone isn't a very good predictor of future performance, so it makes sense to drop it. Performance can still seep into our assessments of the other pillars. For example, a quality strategy that fails to provide good downside protection or that has high tracking error may receive a lower Process Pillar rating than one that looks better on those metrics.

Of course, price is important. But rather than assessing price qualitatively, the new ratings framework mechanically subtracts funds' expense ratios from their gross-of-fees alpha estimate.

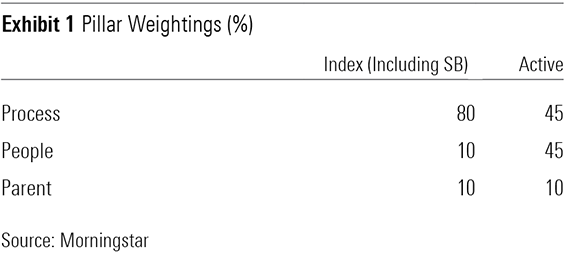

The relative importance of the pillars differs for active and passive funds. Process is the most important for index funds because the index construction methodology determines the composition of the portfolio, leaving little room for the portfolio managers to influence performance. And because index portfolio managers are tethered to an index they can't control, the People Pillar doesn't move the needle as much here as it can for active funds. That's why the Process Pillar gets a larger weighting for index funds (both passive and strategic-beta) than it does for active funds, while the People Pillar gets a smaller weighting, as Exhibit 1 shows.

The ratings model translates the pillar scores into a gross-of-fees alpha estimate by summing the products of each pillar's weighting, score (which is on a five-point scale of Low, Below Average, Average, Above Average, and High), and the richness of the opportunity set. The latter is measured as half of the interquartile range of alphas from the peer group distribution. If all three pillar ratings are Average, the fund's gross-of-fees alpha estimate will be 0. However, if one of those pillars is Above Average, the fund will receive a positive gross alpha estimate. The magnitude of that adjustment depends on the pillar score and the richness (width) of the opportunity set.

The expense ratios for each fund's share classes are subtracted from these gross alpha estimates to create net-of-fees alpha estimates at the share-class level. So, different share classes of the same fund may have different ratings depending on their fees.

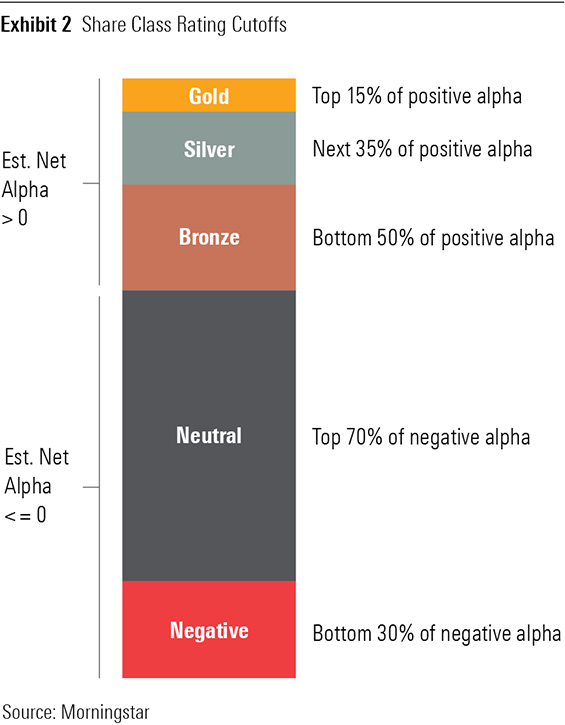

All share classes of active and strategic-beta funds in each category are ranked on their net-of-fees alpha estimates. Morningstar Quantitative Ratings fill in the gaps by providing net-of-fees alpha estimates for funds that Morningstar analysts do not cover. To be a Morningstar Medalist, each active share class must have a positive net-of-fees alpha relative to its category index. Passive funds are ranked against each other in a similar way, but these funds need only have a positive net-of-fees alpha relative to the category median to get a medal. Exhibit 2 summarizes the cutoffs for each rating.

If a passive fund has an Average Process Pillar rating, the highest analyst rating it can receive is Bronze. We also apply buffers to ensure that small differences in fees don't yield big differences in ratings for passive funds. Ultimately, our analysts are still the driving force behind these ratings. In some cases, we may override the model if the output doesn't make sense. For example, if two funds track the same index at a similar price, but one has higher Parent and People Pillar ratings than the other, the analyst may decide it's appropriate to give them the same rating, even if the model disagrees. However, the model anchors the ratings and serves as the default. It is incumbent upon the analysts to get the pillar ratings right.

Process Our assessment of index construction methodology is the main driver of the Process Pillar ratings for index funds, though the managers' index replication approach is also a factor. Here, we're looking for a process that will likely give the fund an edge against its category peers or, for strategic-beta funds, its category index. Strong index strategies tend to be:

- Representative of their investment style;

- Sensible;

- Transparent;

- Turnover-conscious;

- Diversified;

- Easy to replicate.

It isn't necessary for an index to tick all these boxes to receive an Above Average Process rating.

People The People Pillar rating for index funds reflects the strength of the portfolio management team and how well we think it can provide high-fidelity and cost-efficient index tracking. Strong teams tend to have:

- Appropriate staff and workloads;

- Stability;

- Minimal key-person risk;

- Strong supporting infrastructure;

- Regular and independent risk oversight;

- Compensation tied to index-tracking performance;

- Appropriate tools to mitigate transaction costs and tracking error.

Parent The focus of the Parent Pillar rating is the same for active and passive funds. This assesses the asset managers' capabilities and willingness to put investors first. Strong parents:

- Have a culture of stewardship;

- Have a strong product lineup;

- Align the managers' interests with investors';

- Attract and retain top talent;

- Invest in their investment teams;

- Close funds as they reach capacity;

- Have a strong record of regulatory compliance.

A Step Forward The new ratings framework is more complex than the one it replaced, but it should be worth the effort. It should improve ratings efficacy by bringing more structure and consistency to the ratings process and elevating the importance of fees, which is one of the best predictors of fund performance. However, it won't be perfect. We will continue to learn from our successes and failures and use that feedback to continue to improve the ratings.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)