Should You Own a Muni Fund?

Unless you’re in one of the highest tax brackets, the tax advantages might be smaller than you think.

Investors have been pouring money into municipal-bond funds. For the trailing one-year period ended November 2019, inflows into all municipal-bond fund categories totaled about $95 billion--the highest annual inflow since 2009. Taxable-bond funds still hold far more assets overall, but municipal-bond funds have been gaining ground, with nearly $850 billion in total assets as of Nov. 30, 2019. The appeal of these funds is largely based on their tax-advantaged status. In the wake of the 2018 tax law changes, fewer people can itemize deductions, which makes investment vehicles that help reduce taxable income more compelling.

But before you join the tax-wary hordes, it's worth taking some time to figure out how much--if anything--a municipal-bond fund can actually save you. For most taxpayers, there's no longer a significant yield advantage for muni funds after you take taxes into account. The best way to figure this out is to calculate a taxable-equivalent yield, which allows you to make apples-to-apples comparisons between the aftertax income from taxable and tax-exempt vehicles. To calculate it, take the nominal (or pretax) yield for the tax-advantaged vehicle and divide it by the percentage of income you'll keep after taxes (or 1 minus your tax rate). You can calculate this by hand or by using a bond calculator. The answer represents how much income you would have to receive from a taxable investment to make it more competitive than the municipal choice.

For example, if you're in the 32% tax bracket and own a municipal-bond fund with a nominal yield of 1.58%, you'd have to earn more than a 2.32% yield (or 1.58 divided by 0.68) from a taxable investment for the latter to be more attractive after taxes. That calculation doesn't include any adjustments for state or local taxes, so if you live in a high-tax state, you can garner additional tax benefits by choosing a fund that invests in bonds issued within your home state.

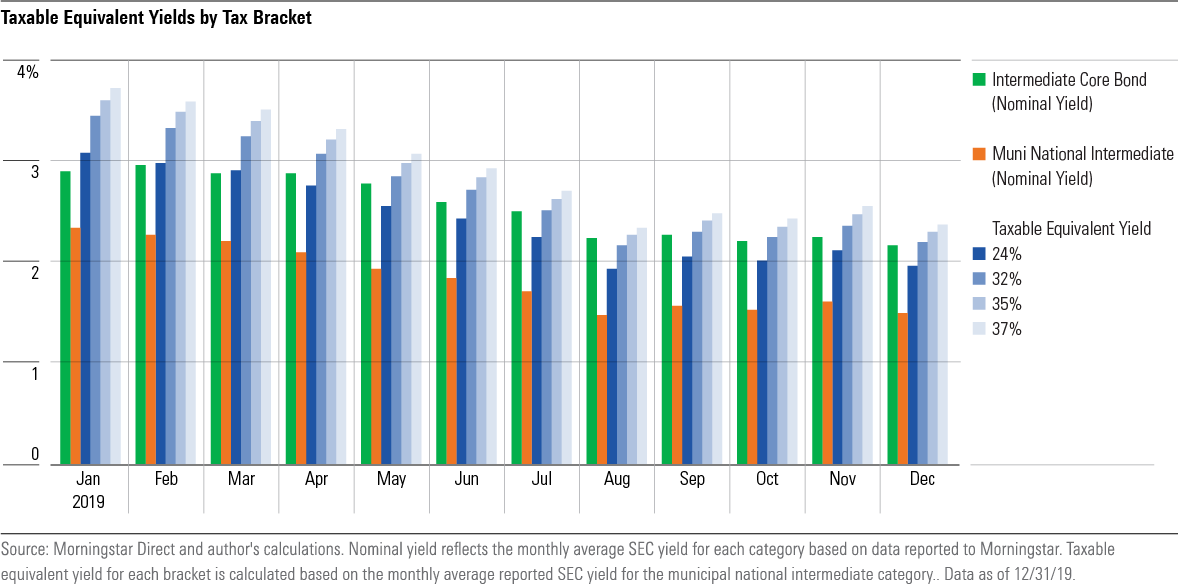

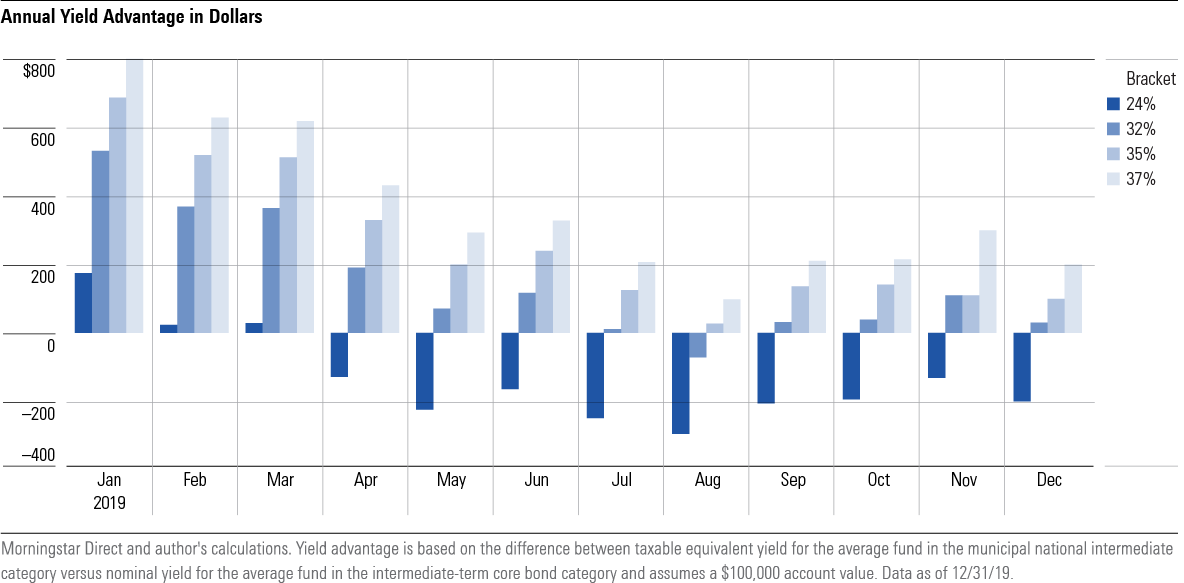

But if you don't live in a high-tax state or prefer to avoid state-specific funds, the yield advantages have been getting smaller. Indeed, the yield advantage for municipal-bond funds has been steadily shrinking over the past 12 months as the stampede into munis has depressed yields, which move inversely with bond prices. (Note: We focused our analysis on the intermediate-term municipal-bond category, which now claims more assets than the short- or long-term categories.) As shown in the chart below, for investors in the 24% tax bracket, taxable-equivalent yields on intermediate-term municipal-bond funds have been lower than nominal yields on intermediate-term core bond funds since about April 2019. That means there's no tax advantage even for investors with taxable incomes high enough to push them into the 24% bracket, which starts at $171,050 for taxpayers who are married filing jointly in 2020.

Investors in the three highest tax brackets (32%, 35%, and 37%) can still garner tax advantages from munis, but the benefits are smaller than they used to be. As of December 2019, for example, the gap between taxable and tax-equivalent yields was only 3 basis points for investors in the 32% bracket and 10 basis points for investors in the 35% tax bracket. Investors in the top 37% bracket could eke out 20 additional basis points versus the average intermediate-term core bond fund. Whether that's a big enough advantage depends partly on how much money you're working with. For a $100,000 account, the tax savings for the 37% bracket translates into about $200 per year. That's better than nothing but doesn't make investing in munis a slam-dunk unless your account value is much higher.

If you've decided to go the muni route, make sure to consider more than just yield, though. As always, expenses are paramount. The average fund in the intermediate-term municipal-bond category has an expense ratio of 0.49%, but lower is better. That's especially true given the narrow range of returns for fixed-income funds. In particular, passively managed index funds can be a compelling option for cost-conscious investors because of their low expense ratios. As my colleague Neal Kosciulek recently pointed out, index-based municipal-bond funds have gotten better at tracking their benchmarks in recent years despite the challenges of the municipal market, with its sprawling size, limited liquidity, and larger number of unrated bonds. In the intermediate-term bond category, investors can now choose from several passively managed open-end funds and exchange-traded funds from fund families including Fidelity, iShares, and Vanguard.

Credit quality is another important consideration, especially given the shaky state of many state and local budgets. Funds that bill themselves as high-yield often dip into lower-credit-quality rungs, but that has led to heavier losses during bond market downturns, such as 2008, when the average high-yield municipal-bond fund lost 25%. Although default rates on municipal-bond funds have typically been low overall, potential or actual defaults can roil the market from time to time. The city of Detroit filed for bankruptcy back in 2013, as did the city of Stockton, California the same year. The U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, whose bonds were widely owned by U.S.-based funds, went into a debt crisis starting in 2014 and eventually defaulted on its debt. Morningstar's home state of Illinois (and home city of Chicago) has long suffered well-publicized budget deficits and unfunded pension obligations. For high-yield municipal bonds, liquidity is a related risk factor that can lead to heavier losses during periods of market stress.

The municipal-national intermediate Morningstar Category offers less generous yields but is a safer bet in terms of credit quality and default risk. Within the municipal-national intermediate category, the typical fund invests about 80% of its assets in the top three credit-rating categories, with most of the remainder in middle-tier credits rated BBB. The average fund in the high-yield municipal category, on the other hand, about 25% of its assets in bonds rated BBB, with an additional 21% of assets in sub-investment-grade issues and 26% in unrated credits. These funds offer a bigger yield advantage, but investors tempted to stretch for yield should keep in mind that these funds have suffered significant losses in previous economic downturns. That's especially worth noting now that we're in the 11th year running of the current economic recovery.

Another key question is whether to invest in individual bonds or in a diversified mutual fund. If you have a brokerage account, you can generally buy individual municipal bonds in increments as low as $5,000. But while transaction costs for trading municipal bonds have declined significantly, they're still relatively high. The Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board estimates that the average spread between buy and sell prices was about 80 basis points for retail investors as of April 2018. These transaction costs would eat up much of the tax advantage of holding individual bonds unless your portfolio is large enough to buy bonds in larger increments. Even then, you'd probably need to buy at least 20 higher-quality bonds to help mitigate bond-specific risk. And because the municipal-bond market is notoriously opaque and illiquid (though less so than it used to be), you should also plan on holding any individual bonds until maturity.

Finally, make sure to consider municipal-bond funds in the context of your entire portfolio. For obvious reasons, you’d only want to hold them in a taxable account. Because they have a negative correlation with larger-cap domestic equities, municipal-bond funds can plan a strong role in helping diversify your portfolio. But given the risk inherent in the municipal market, it’s also worth including some other bond-fund categories, such as U.S. government-bond funds, which have an even lower correlation with stocks. And municipal bond funds won’t help protect your portfolio against inflation, so it makes sense to add other types of bonds, such as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, to the tax-deferred portion of your portfolio.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)