What Investor Biases Are Agreeables Most Prone To?

Contributor Michael Pompian shares the results of his new study of personality traits and investment biases.

This is the fifth article in a series focusing on the Big Five personality traits and how they relate to the behavioral biases of investors. Over the years, I have followed a debate between the effectiveness of the Myers-Briggs test versus another widely used personality test, the Big Five. More recently, the debate has intensified. I decided to conduct a study of the Big Five. Specifically, I studied 121 investors, examining the relationship between the Big Five and investor biases. Why? Because taking the time to understand the underlying personality of the investor leads to better advice and results.

This month’s article examines the second of the Big Five traits: agreeableness.

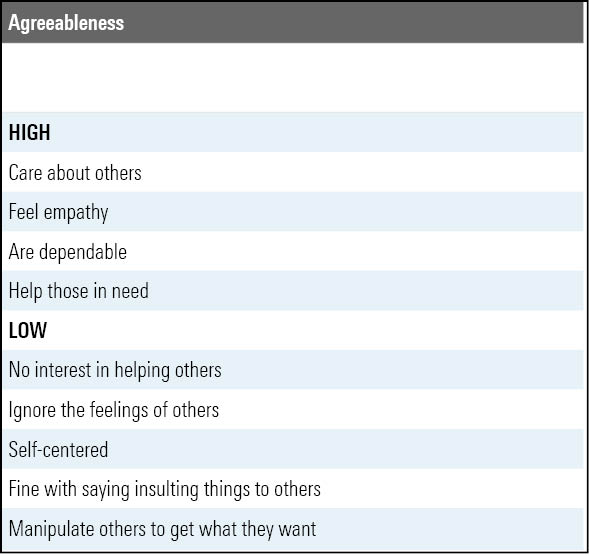

Agreeableness People high in agreeableness tend to be trustworthy, kind, affectionate, and altruistic. Agreeable clients tend to be cooperative and easy to work with, while those low in this trait tend to be more competitive and/or manipulative.

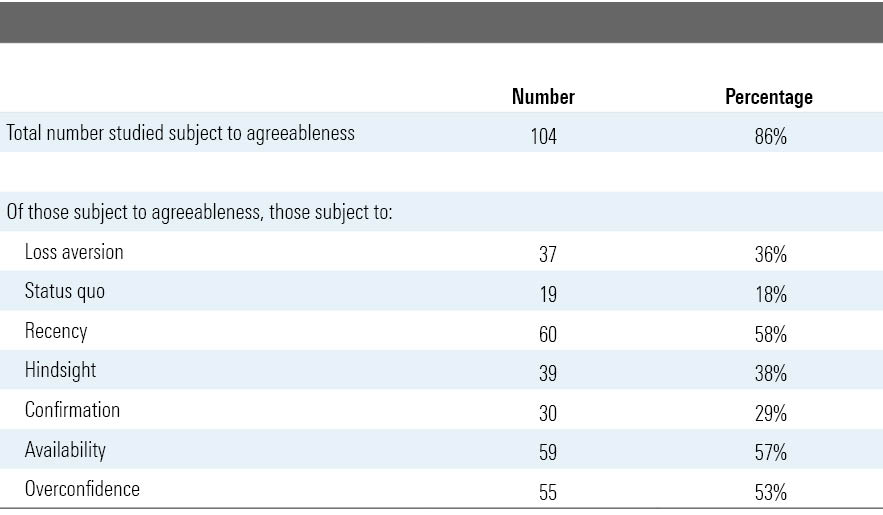

The Study I tested 121 investors for the Big Five personality traits and for the following investor biases: loss aversion, status quo, recency, hindsight, confirmation, availability, and overconfidence.

The results of the study show what percentage of the population surveyed is (a) subject to each of the Big Five traits and (b) subject to each of the biases. For those personality traits that have a large percentage of respondents subject to a given bias, we will discuss strategies to work with clients on these behaviors.

These are the results for agreeableness:

Analysis of Results Per the exhibit above, 86% of the 121 people surveyed were subject to agreeableness. Of these 104 people, you can see the percentages that were subject to the various biases. The highest percentage of those subject to agreeableness are also subject to recency. The next two most common biases among agreeables were availability and overconfidence. Let's unpack each of those biases below.

Recency Bias Recency bias, an information processing bias, occurs when people more prominently recall and emphasize recent events and observations than those events that occurred in the near or distant past. Humans have short memories in general but especially when it comes to investing cycles.

Consider the following simple example of recency bias. Suppose that a passenger is peering off the observation deck of a cruise ship and spots precisely equal numbers of green boats and blue boats over the duration of the trip. However, if the green boats pass by more frequently toward the end of the cruise, with the passing of blue boats dispersed evenly or concentrated toward the beginning, then recency bias could influence the passenger to recall, following the cruise, that more green than blue boats sailed by.

In the investment realm, one of the most obvious and most destructive manifestations of recency bias among investors pertains to their misuse of investment performance records. For instance, investors often make investment decisions based on outsize returns during a one-, two-, or three-year period. As many wealth managers know, recency bias ran rampant among investors during the bull market in U.S. real estate between 2003 and 2007. Many investors implicitly presumed, as they have during other cyclical peaks, that the real estate market would continue its enormous gains forever. They all but forgot the fact that bear markets can and do occur.

Advice: This behavior is relatively difficult to overcome, as investors can often be persuaded by strong returns. To counteract the effects of the recency bias, many practitioners wisely use what has become known as the "periodic table of investment returns," an adaptation of the scientific periodic table of chemical elements. Because many investors do not pay heed to the cyclical nature of asset-class returns, securities that have performed spectacularly in the very recent past appear unduly attractive. If you look at the table, you'll see that often the best-performing asset classes in one year or two years in a row are at the bottom of the table in subsequent years. This is the nature of investing.

Availability The availability bias, another information processing bias, is a rule of thumb, or mental shortcut, that causes people to estimate the probability of an outcome based on how prevalent or familiar that outcome appears in their lives. People exhibiting this bias perceive easily recalled possibilities as being more likely than prospects that are harder to imagine or difficult to comprehend.

Investors will often choose investments based on information that is available to them (for example, advertising, suggestions from advisors, friends, and so on) and will not engage in disciplined research or due diligence to verify that the investment selected is indeed suitable for the situation. The result of availability bias is that investors may not choose the best investments for their portfolios and end up with suboptimal returns.

A simple example of availability bias is choosing a mutual fund based on those that do the most advertising. Because the information is available, many investors simply go with the one they’ve heard of most. In reality, there are many high-quality funds that do no advertising but can be found via research services. Because this may present a burdensome endeavor, some investors simply choose the most readily available information for their decision-making.

Advice: Investors will choose investments that resonate with their own personality or that have characteristics they can relate to their own behavior. As a result, investors often ignore potentially good investments because they can't relate to or do not come in contact with characteristics of those investments. To to overcome availability bias, investors need to carefully research and contemplate investment decisions before executing them. Focusing on long-term results is the best approach rather than following current investing trends without a plan to overcome availability bias. As an advisor, you should be aware that everyone possesses a human tendency to mentally overemphasize recent, newsworthy events. Refuse to let this tendency compromise your advice to your client. The old axiom that "nothing is as good or as bad as it seems" offers a safe, reasonable recourse against the impulses associated with availability bias.

Overconfidence In its most basic form, overconfidence bias is unwarranted faith in one's intuitive reasoning, judgments, and cognitive abilities.

For example, in spite of an enormous body of evidence illustrating that drinking impairs a person’s ability to drive safely and react quickly, drivers continue to get behind the wheel after they’ve had too much to drink. If you suggest they shouldn’t, the typical responses are “I’m OK” or “I can handle it” or “I am one of those people who isn’t affected by alcohol like other people.” They are overconfident in their abilities to drive under the influence and assume they can beat the safety odds better than everyone else. Similarly, investors exhibiting the overconfidence bias overestimate their abilities, sometimes with disastrous consequences. They buy stocks without doing research or try to guess the direction of the market without realizing that the market’s direction from day to day isn’t predictable.

Advice: I have seen overconfidence in action many times in my practice. To counteract this behavior in my clients, I often recommend they establish a "mad money" account. This involves taking a small portion of one's wealth for "overconfident" trading activities while leaving the remainder of their wealth to be managed in a disciplined way. This approach scratches the itch that many investors have to trade their account, while at the same time keeping the majority of the money intelligently managed.

Michael M. Pompian, CFA, CAIA, CFP is an investment advisor to family office clients and is based in St. Louis. His book, Behavioral Finance and Wealth Management, is helping thousands of financial advisors and investors build better portfolios of investments. Contact him at michael@sunpointeinvestments.com.

The author is a freelance contributor to Morningstar.com. The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect the views of Morningstar.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6NPXWNF2RNA7ZGPY5VF7JT4YC4.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_1997613e43634249b59dd28db9b24893_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)