The 2020 Retirement Landscape

Contributor Mark Miller examines how his predictions for 2019 turned out and shares his expectations for 2020.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to reflect news about the SECURE Act.

Accountability matters, and this column began the year with some predictions on the key developments for 2019 on the retirement beat. As the year wraps up, it seems only fair to consider how accurate my calls were--and to toss out some fresh predictions for 2020.

I thought that 2019 would be a year for some achievements in the policy arena aimed at helping people save for retirement. I also noted that Congress would try to save the pensions of more than 1 million retirees in multiemployer pension plans and that the SEC would move toward adoption of its Regulation Best Interest.

And, on the very day this column was published, news broke that the SECURE Act, which would offer new ways for small employers to band together to offer 401(k) plans to workers, will become law this year. Lawmakers will not solve the multiemployer pension crisis--at least not this year. Reg BI is in place, but some experts see the fiduciary battle--now entering its third decade--continuing into the new decade.

Let’s break it down.

Retirement Saving Looks like I got this one right: the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement Act of 2019 (SECURE Act) is included in a year-end spending package headed for approval by Congress this week and President Trump's signature.

The legislation was approved by the House in May and has been sitting around ever since in the Senate. The legislation enjoyed broad bipartisan support, but it had been hung up on pet issues of a handful of senators who are able to shelve legislation at will. So the fact that the law squeaked through this year just demonstrates the old saying - even a broken clock is right twice a day.

The SECURE Act expands opportunities for small employers to join multiple-employer plans, or “open MEPS.” Plans would be offered by private plan custodians; architects of the open plans think small employers will be enticed by reduced costs, streamlined paperwork, and an increased tax credit to cover setup costs. It also aims to encourage employers to add annuities to their retirement plans by creating a safe harbor protecting them from liability. That idea worries consumer advocates, who see it as a sop to insurance companies that want to peddle high-cost lifetime income products to workers at the point of retirement.

The law also:

- Tightens the rules for distributions from "stretch" IRAs

- Pushes back the age when RMDs must begin to 72

- Repeals the maximum age for making contributions to traditional IRAs

- Encourages incorporation of annunity products in workplace plans

- Requires employers to provide illustrations to workers of how their savings will translate into income streams in retirement

Elsewhere, California and Illinois launched state-sponsored auto-IRA programs. Employers would be required to sign up and to autoenroll workers. Eight other states are working on similar saving plans.

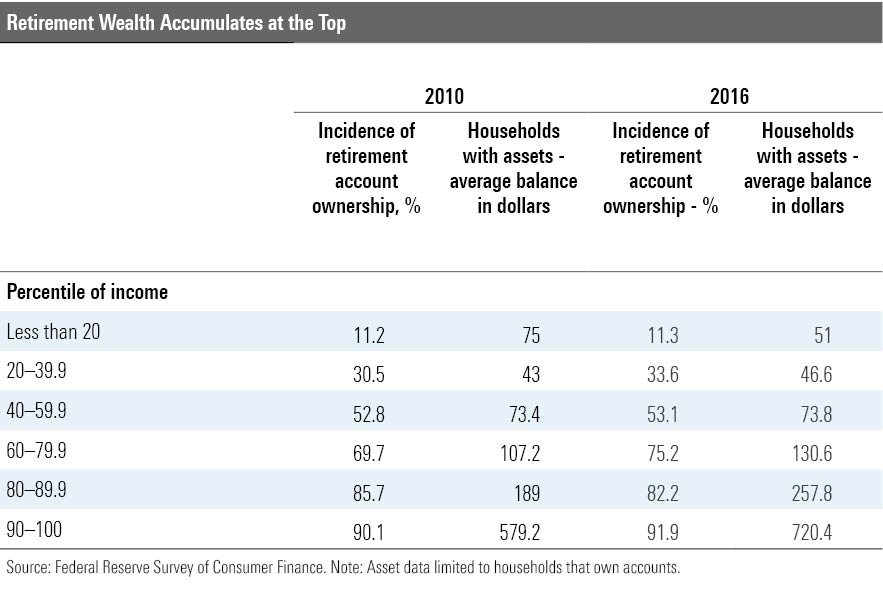

Both of these ideas--the SECURE Act and auto-IRAs--take aim at the same problem: Retirement wealth is accumulating exclusively among affluent households.

There’s a great deal of debate about whether there is a retirement crisis or not. My take is fairly simple: More than half of U.S. households have no wealth to fall back on for retirement when you consider financial assets and home equity. Crisis deniers usually come back with this: “Yes, but those folks will be able to live on Social Security, which has a progressive benefit formula that replaces a higher percentage of preretirement income. So, they’ll be fine.”

This channeling of Marie Antoinette misses two key points.

First, the average monthly Social Security retirement benefit for a worker claiming at full retirement age in 2018 was $1,523--not much to live on, considering high inflation rates for medical care and housing.

Second, when you consider not just savings and home equity but Social Security and pensions, things still look bleak for much of the country. The Employee Benefit Research Institute's projections of retirement risk find that in 2019, the odds for households near retirement (born 1955-1964) of having sufficient resources to last throughout retirement are 93% for the top income quartile, 79% for the third quartile, just 55% for the second quartile, and a horrible 11% for the lowest quartile. The odds have improved sharply since the recession ended for all but the lowest quartile, which actually saw its prospects deteriorate badly over the course of the decade.

Multiemployer Pensions I forecast that Congress would try to avert an insolvency crisis in multiemployer pension plans, which would threaten the retirement of more than 1 million workers and retirees. I was correct--lawmakers did try. But they have not succeeded, and action before the 2020 elections now seems unlikely, as the House and Senate are at complete loggerheads over how to solve the problem.

About 1,400 multiemployer plans cover 10.6 million workers and retirees, according to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, the federally sponsored insurance backstop for defunct plans. Multiemployer plans are created under collective bargaining agreements and jointly funded by groups of employers in industries like construction, trucking, mining, and food retailing.

Plans covering 1.3 million workers and retirees are badly underfunded. And PBGC projects that its multiemployer insurance program will run out of money by the end of the 2025 fiscal year, absent reforms.

The House of Representatives passed legislation in July to address the problem, built around providing low-interest loans to struggling plans. The Senate sees it differently, and several key committees issued their own plan last month in the form of a white paper. The latter plan would boost substantially the premiums that plan sponsors pay into the system and would add premiums paid by retirees as well, which would effectively act as a benefit cut. It also contains reforms to the discount rate assumptions plans use to project future health.

“Republicans perceive the House bill as nothing but a bailout--government will give these funds money and never get paid back,” says Gene Kalwarski, CEO of Cheiron Inc., an actuarial consulting firm. “Democrats think the Senate plan would make healthy plans fail.”

Time is running short--the Teamsters’ Central States fund, which has more than $26 billion in unfunded pension obligations, is projected to fail in 2025. That would exhaust the PBGC multiemployer fund. Meanwhile, seven multiemployer plans failed this year, and the plan covering mineworkers is scheduled to fail in 2023.

Fiduciary Protections I predicted that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission would move toward adoption of a best interest standard for financial advice this year--and the SEC did adopt its so-called Regulation Best Interest, which defines standards for brokers who sell investment products and explains the duties of investment advisors who provide financial guidance.

The SEC rule comes on the heels of the death of a fiduciary protection rule governing retirement advice implemented by the U.S. Department of Labor. The DoL rule died in 2018, when courts sided with opponents in the financial services and insurance industries, ruling that the department had overstepped its authority.

Many critics regard the SEC regulation as too weak, relying heavily on disclosure to clients of any conflicts of interest. As Morningstar notes in its official take on the subject, the regulation "will also further muddy the difference between the broker business model (which is based on commissions) and the Registered Investment Advisor model (which is largely, although not always, based on charging a fee based on assets under management.)"

I suspect that this battle is not over. Reg BI was adopted on a strictly partisan vote among the SEC commissioners; if a Democrat wins the White House in 2020, partisan control of the SEC will shift yet again, and Reg BI likely will be high on the list of topics to revisit.

Next Year As you may have noticed, 2020 is an election year, so don't expect significant policy developments in Washington. The SECURE Act might squeak through--perhaps tacked onto a broader omnibus bill--since its support is fairly broad, but that's about it.

Social Security reform will await the next Congress and presidential administration. The program's combined retirement and disability trust funds, or OASDI, are forecast to be exhausted in 2034. At that point, the program would be able to pay about 77% of scheduled benefits from incoming payroll taxes. That would mean a fearsome across-the-board benefit cut for current and future claimants.

There is still time to fix that problem. The good news, from my perspective: The longer Congress waits, the odds rise that the solution will involve only new revenue, not benefit cuts. This is an actuarial point--the closer we get to 2034, restoring trust fund solvency via cuts becomes much more difficult.

Meanwhile, the clock will keep ticking on the multiemployer pension fund mess. Considering the magnitude of this problem, it’s stunning that there is so little media attention focused on it. Maybe that will change in 2020, but somehow I doubt it.

Happy New Year--and stay tuned.

Mark Miller is a journalist and author who writes about trends in retirement and aging. He is a columnist for Reuters and also contributes to WealthManagement.com and the AARP magazine. He publishes a weekly newsletter on news and trends in the field at Retirement Revised. The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)