What Are Retirement Income Funds? Do You Need One?

Converting your savings to a paycheck in retirement is harder than you might think.

With the first wave of the 76 million Americans born between 1946 and 1964 now heading into retirement, there should be a huge need for products that help investors convert accumulated wealth into regular income. But retirement-income funds haven’t really taken the fund industry by storm. There are currently about 110 mutual funds and collective investment trusts (not including multiple share classes) in Morningstar’s Target-Date Retirement Category with a total of roughly $73 billion in assets. That’s a small sliver of the $1.7 trillion invested in target-date strategies overall.

Benefits of Retirement-Income funds Retirement-income funds have a few things going for them. These funds are often designed to be the terminal portfolio for investors who are investing their retirement assets in a target-date fund. After the fund reaches its target date, many employer plans will eventually roll over the assets to a retirement income fund. Investors who like the simplicity of an all-in-one portfolio that gives them exposure to a diversified set of asset classes can therefore easily transition into a similar fund after retirement.

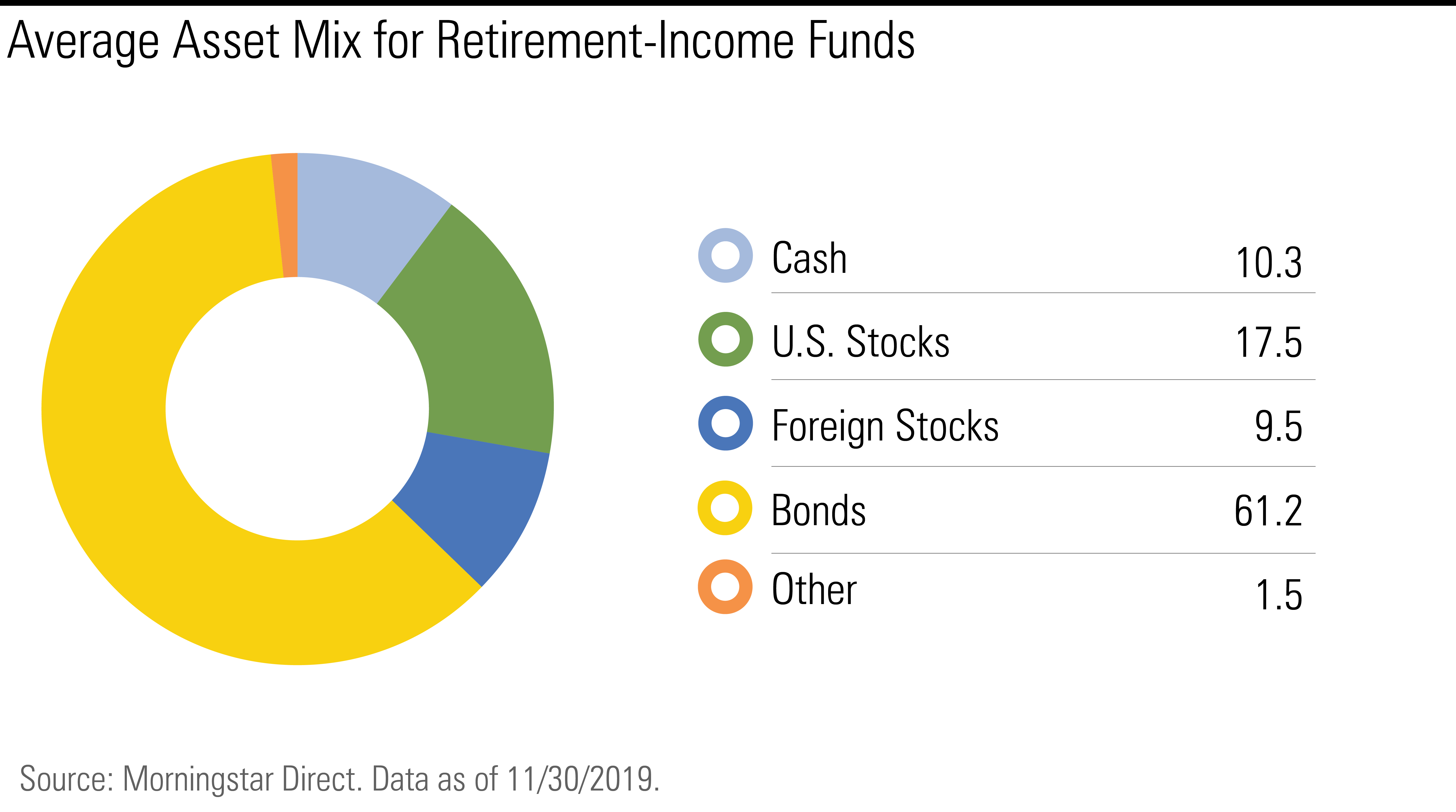

While target-date funds will shift their asset-allocation mix (also known as the glide path) to become more conservative over time, retirement-income funds have a more static asset mix. The typical retirement income fund invests about two thirds of its assets in fixed-income securities, with most of the rest in equities. As part of this overall stock/bond mix, they also offer exposure to non-U.S. stocks and bonds, as well as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities to help guard against inflation. Protecting a portfolio against inflation is especially important for retirees, who no longer have the built-in inflation hedge of a regular salary (which typically increases over time).

As suggested by their name, retirement-income funds are also designed to provide retirees with income from fund distributions. The average retirement income fund has paid out 2.4% to shareholders over the past 12 months--a bit higher than you could earn by investing in a diversified domestic-equity fund.

The Drawbacks Most retirement-income funds suffer from a few key shortfalls, though. For one, they're pretty light on equities for all but the oldest retirees. Therefore, they may not offer enough appreciation potential to support a sustainable withdrawal rate that matches retirees' actual spending. I use Morningstar's Lifetime Asset Allocation indexes as a benchmark for this. For an investor planning to retire in 2020 who has a moderate level of risk tolerance, for example, we typically recommend keeping about 46% of a portfolio in equities. The typical retirement income fund's 27% equity weighting falls well short of that.

A heavy fixed-income weighting means investors run a real risk of either running out of assets or having to cut spending later in life to avoid depleting their portfolios. Indeed, some academic research has found that a portfolio’s “success rate” (defined as the percentage of time a portfolio doesn’t run out of money despite regular withdrawals) rapidly declines for retirement portfolios with fixed-income stakes greater than 50%. [1]

Second, the income these funds generate may not be enough to cover all of a retiree’s living expenses. That’s especially true during the roughly five-year gap between when an individual first retires at 65 and when required minimum distributions kick in (the year he or she turns 70 and a half). Even assuming a relatively lavish $1 million account balance, the typical retirement income fund would only generate $23,800 in annual income. Most retirees would probably hard to find it tough to live on that unless they have other sources of income or have already started taking Social Security benefits. Investors could make portfolio withdrawals to supplement the shortfall, but that would run counter to the idea of investing in a single fund that doesn’t require making a lot of transactions or investment decisions.

Other Options for Retirement Income Outside of the retirement-income funds offered through a target-date fund series, there are a few other fund types that might appeal to retirees seeking income.

Managed payout funds are one option, but there are only a handful of offerings from Vanguard, Schwab, Franklin, and J.P. Morgan. Vanguard Managed Payout, by far the biggest of the bunch with $1.8 billion in assets, currently targets a 4% payment amount. The fund has been somewhat controversial (even among Vanguard aficionados) because it ventures into more esoteric areas such as alternatives and commodities. Vanguard even took the unusual step--almost unheard of for Vanguard--of merging two of its Managed Payout siblings into this fund back in 2014.

The remaining Managed Payout fund has had a relatively strong performance over time. It’s important to note, though, that part of the fund’s distributions come from returns of capital, which will erode principal over time. For the past couple of years, the fund has been paying monthly distributions of $0.0510 per share, about 40% of which has come from returns of capital. These payments shouldn’t be confused with a true income stream, but that might not be a big issue for investors who were planning to withdraw part of their principal anyway.

For investors who really want to streamline retirement income and withdrawals, Fidelity's Simplicity RMD series bundles an age-based asset allocation with an automated withdrawal service for required minimum distributions. There's nothing really hard about taking an RMD--you just take your retirement account's balance as of December 31 of the previous year and divide by the distribution period for your age shown in the IRS worksheet. The answer you get is your RMD amount for the current year. Most brokerage firms will calculate the RMD amount for you and remind you to take it if you haven't already done so. But because there are steep penalties for failing to take the correct RMD, it's an administrative task some investors might want to outsource.

Surprisingly, Fidelity seems to be the only major fund company to offer a fund lineup specifically designed to do that. Fidelity’s Simplicity series of RMD funds offers reasonable expense ratios and a well-thought-out asset mix that should support a sustainable withdrawal rate. The funds also adjust their glide paths over time until they reach a landing point with a lower equity weighting suitable for older investors.

Multi-asset income funds, while not specifically geared toward retirement income, can be another option for investors looking to generate income in retirement. On average, they’ve paid out about 3.5% over the past 12 months. They also typically tilt a bit more toward the equity side than retirement-income funds, with an average equity weighting of 42%. There are a couple of caveats, though. The average expense ratio is pretty steep, at 1.0%. Not coincidentally, these funds are often tempted to stretch for yield by dipping into lower credit-quality bonds. The average multi-asset income fund holds about 17% of its assets in bonds rated BB, another 17% in bonds rated B, and 5% in bonds rated below B. These all qualify as junk bonds and can suffer price declines or defaults during economic downturns. Partly because of their credit-quality exposure, multi-asset income funds are more prone to losses than some other income-oriented funds.

Finally, traditional balanced funds can be another option for retirement income. While Morningstar now divvies up the fund universe into several asset-allocation categories, the classic balanced fund offers a simple mix of equities and fixed-income holdings, typically with slightly more on the equity side. This asset mix offers enough equity exposure to help hedge against longevity risk, but also a healthy dose of fixed-income holdings for stability. But the 1.8% average yield for balanced funds is probably on the skimpy side for income-hungry retirees. In addition, many balanced funds are light on some of the asset classes retirees should have exposure to (namely TIPS).

While existing retirement income offerings sound good in theory, they haven’t really proven themselves a compelling option for investors who need regular income. Instead, most retirees would probably be better off putting together an income and withdrawal strategy that’s more tailored to their specific needs. One way to do this would be to start with a bucket portfolio, which typically sets aside one or two years of living expenses in cash to facilitate spending and buffer volatility. Another option is to simply target a sustainable withdrawal rate (4% is a reasonable starting point) and adjust as needed for inflation or significant market upswings or downturns. Immediate or deferred annuities can also be an attractive alternative, especially for investors who worry about outliving their assets and like the security of a fixed monthly payout.

At the end of the day, the fund industry has done a decent job simplifying wealth accumulation by rolling out target-date funds and other all-in-one offerings. But decumulation strategies (including retirement income) are multidimensional issues that involve several different variables--including spending, longevity risk, inflation, and market returns. It’s hard to solve this problem with any single product offering, especially in a mutual fund (as opposed to annuity) format. For retirees looking to tap into the wealth they’ve already built, generating retirement income remains a difficult task.

[1] Cooley, P. L., C. Hubbard, and D. Walz, 2011. "Portfolio Success Rates: Where to Draw the Line." Journal of Financial Planning 24, 4 (April): 48-60.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)