Understanding Medicare Surcharges

Wealthy enrollees pay more for premiums--how can you avoid it?

Medicare benefits are the same for everyone in the program--but the wealthy pay more for them.

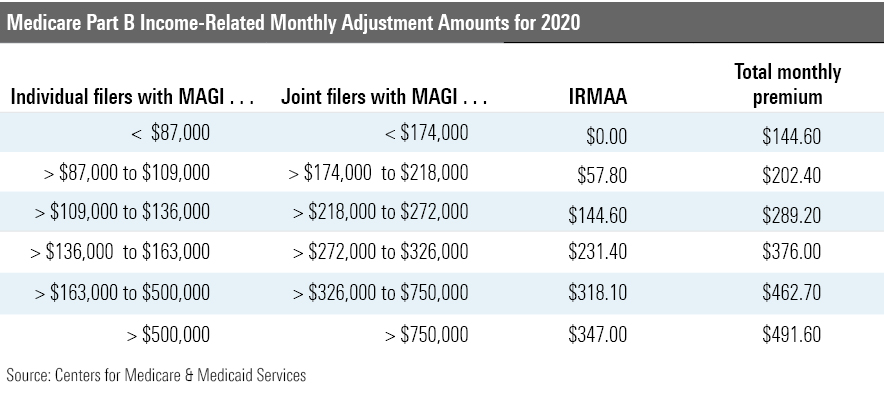

Since 2007, high-income enrollees have been paying surcharges on their premiums for Part B (outpatient services) and Part D (prescription drugs). Relatively few people on Medicare pay the so-called income-related monthly adjustment amount, or IRMAA--but the surcharges can be steep. The brackets that determine who pays IRMAA will be tweaked in 2020 in a way that will get some people off the hook, at least temporarily; that makes this a good time to consider how IRMAA is structured, how it is changing, and how you might be able to avoid paying it.

IRMAA became law as part of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, which is known mainly for having created the Part D benefit. Congress' intent was to help shore up Medicare's finances as program costs accelerate.

Under IRMAA, Medicare enrollees with income exceeding certain levels pay a higher share of total Part B program costs. The standard premium covers 25% of Part B program costs, while those subject to IRMAA pay anywhere from 35% to 85% of those costs. The same percentages are applied in Part D, calculated as a percentage of the national base premium.

The IRMAA can create surprises for people when they first retire and sign up for Medicare but are not aware of this means-testing. IRMAA affects about 7% of Medicare enrollees, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

All that said, Medicare remains an excellent deal even if you must pay high-income surcharges. In 2016, the average person with Original Medicare coverage spent $5,460 out of their own pocket for healthcare, according to Kaiser. That included costs for Part B, Part D, and a Medigap supplemental plan. In return, these folks could visit any physician or hospital in the United States that accepts Medicare--how many health insurance plans are you aware of that provide that breadth of access? And the Medigap policy meant that they bore little, if any, additional out-of-pocket expenses.

In 2020, IRMAA might tack on anywhere from $690 to $4,200 (annually) per enrollee to that figure--not inconsiderable, but manageable for those with high income.

How high? Let's look.

IRMAA brackets are defined by a modified-adjusted-gross-income, or MAGI, formula that includes the total adjusted gross income on your income tax return plus tax-exempt interest income. The determination is made using the most recent tax return made available by the IRS to the Social Security Administration. For example, the IRMAA you pay in 2019 would be based on the adjusted gross income reported on your 2017 tax return.

Next year, IRMAA will kick in for single filers with MAGI above $87,000, and double that figure ($174,000) for joint filers. From there, the surcharges move up through a series of brackets. It's worth noting that even a single dollar of MAGI past one of these thresholds pushes you into the next bracket (ouch!).

The two-year lag effect can create unpleasant surprises when you first enroll in Medicare if your income has declined substantially since retirement. Here, it's important to note that you can--and should--appeal for a reduction if your income declined owing to any one of a number of defined "life-changing" circumstances--and one of those is stopping work. File your appeal using Form SSA-44 from the Social Security Administration--but I also recommend a visit to your local Social Security office to talk through the process.

High-income seniors also are vulnerable to rising Medicare costs in one other way--they're not protected by the "hold-harmless" provision in federal law. This feature prevents the dollar amount of Part B premium increases from exceeding the dollar amount of Social Security's annual cost-of-living increase. The hold-harmless provision ensures that net Social Security benefits do not fall.

But affluent seniors who pay IRMAAs are among a smaller group not held harmless. That can set up some sizable increases in the base Part B premiums. For example, in 2017, nonprotected enrollees shouldered most of the burden of rising Part B premiums; their premiums jumped sharply, while premiums stayed flat for protected beneficiaries, who paid an average of $109. Congress has tweaked the structure of IRMAA since it was enacted. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 revised the share of Part B and Part D program costs paid by individuals with MAGI of more than $500,000 ($750,000 for couples).

That same law requires that the income thresholds that determine IRMAA payments for most IRMAA brackets be adjusted annually for inflation. This inflation indexing begins in 2020, affecting all but the highest bracket; the highest bracket will follow suit in 2028. The inflation metric to be used is the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, or the CPI-U.

The CPI-U is not expected to keep pace with wage growth, but it should help to reduce exposure to IRMAAs somewhat.

HealthView projections suggest that a large share of affluent households will be subject to some amount of IRMAA over the course of retirement.

"We run scenarios for financial advisors every day, and roughly half of their clients will pay surcharges at some point," says Ron Mastrogiovanni, HealthView's CEO. "It might be a couple thousand dollars, or much more--in some cases, hundreds of thousands of dollars."

Today's younger workers are more likely to trigger IRMAA brackets, he adds. HealthView calculates that a 45-year-old college graduate currently earning $95,000 per year will, by age 65, earn $208,000 (assuming her income grows at Social Security's Average Wage Index projection of around 4%). After an 85% income replacement ratio, her income in-retirement will be $176,000, placing her in the third income bracket under IRMAA.

"Younger people just will have more years of inflation compounding over time," he notes.

Mitigation Strategies For some retirees, IRMAAs will be an unavoidable fact of life--and they might be classified as one of those "good problems to have," if you are fortunate enough to enjoy high MAGI in retirement.

However, some advance planning on your mix of investment products can help mitigate IRMAAs. Strategies that minimize MAGI might include Roth conversions prior to retirement, and favoring a health savings account, if one is available to you, over a traditional tax-deferred vehicle.

Qualified charitable distributions are another possible route, if you are inclined toward philanthropy. QCDs are direct transfers of funds from your IRA, payable to a qualified charity. QCDs can be counted toward satisfying your required minimum distributions for the year; you must be aged 70.5 or older to use QCDs.

HealthView has published a white paper discussing how IRMAA impacts households and mitigation strategies.

Mark Miller is a journalist and author who writes about trends in retirement and aging. He is a columnist for Reuters and also contributes to WealthManagement.com and the AARP magazine. He publishes a weekly newsletter on news and trends in the field at Retirement Revised. The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)