Tailoring Your Portfolio When One Size Doesn’t Fit All

8 scenarios where you may need to tweak your portfolio.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article previously appeared on Nov. 26, 2019.

Editor's Note

A version of this article previously appeared on Nov. 26, 2019.

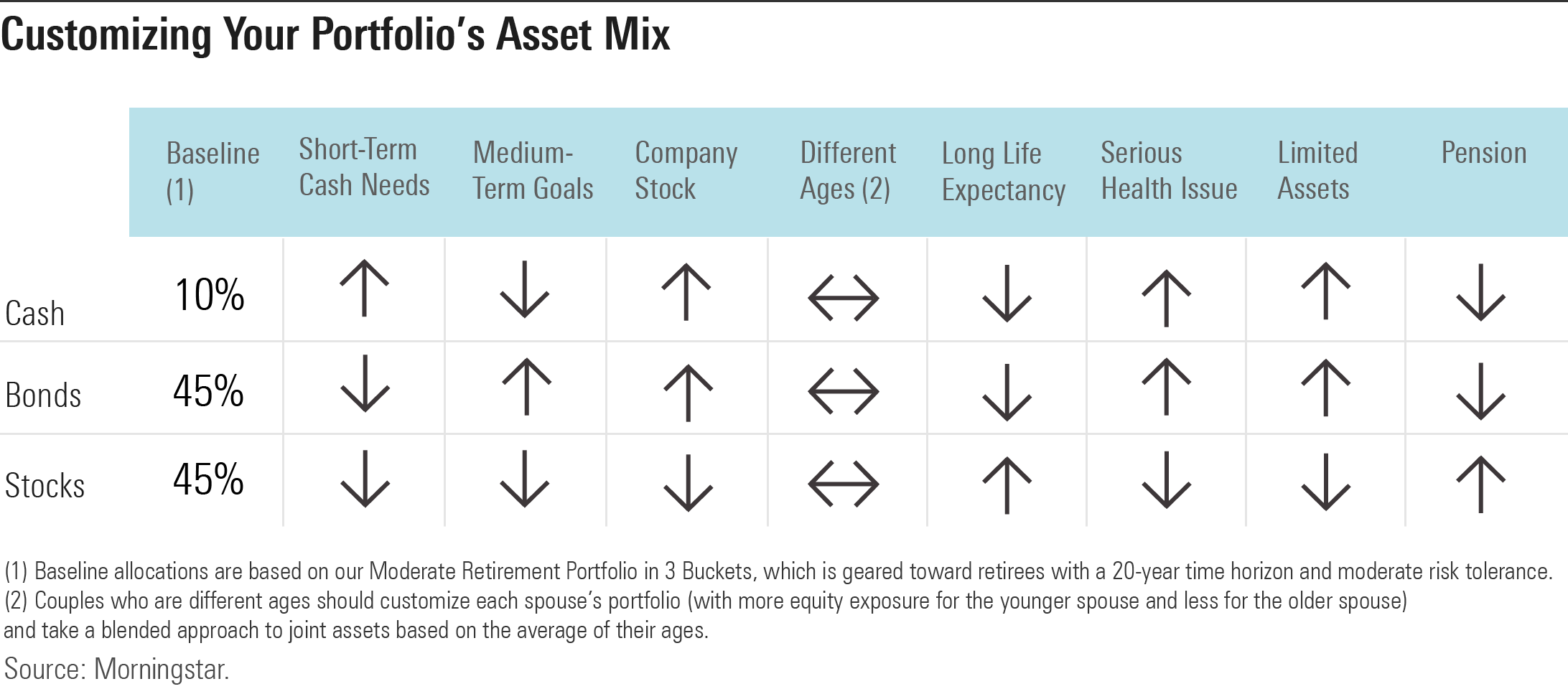

Unless you happen to be an average-size person with perfectly balanced proportions, the clothing you buy may or may not fit perfectly. A skilled tailor can make a wardrobe seem almost custom-made by taking up a hem, adjusting a cuff, or making a few nips and tucks here and there. The same applies to your portfolio. A standard asset-allocation mix (such as a model portfolio) may work well for the "average" investor, but one size doesn't always fit all. Here are some of the situations in which you might want to consider adjusting your portfolio for a better fit.

You Need More Cash for Short-Term Expenses

Looking at your actual spending is crucial, especially when you're first transitioning into retirement. My colleague Christine Benz has done an excellent job explaining the "Bucket approach" to asset allocation, which divides assets into different buckets based on when you expect to use them. This is a great way to tailor your asset allocation to better fit your specific needs. The general idea is to keep one to two years' worth of expenses in highly liquid securities to help meet short-term cash needs (plus an additional five years' or more worth of living expenses in high-quality fixed-income securities to provide income and stability). That way you won't have to scramble to sell securities to meet your ongoing expenses. In effect, this approach is a way of building a tailored asset allocation from the bottom up.

You’re Saving for a Short- or Intermediate-Term Goal

Similarly, make sure your asset allocation accounts for both longer- and shorter-term goals. If you have upcoming events on the horizon such as a home purchase, college tuition, a wedding, or a big vacation, make sure you have enough of your portfolio in moderate-risk assets (such as high-quality short- or intermediate-term bond funds) to fund these goals. As a rule of thumb, you want to match the duration of your assets with that of your liabilities to avoid taking on too much (or too little) risk. (Duration is based on the weighted-average term to maturity of an asset’s cash flows and can also be used as a gauge of interest-rate sensitivity.)

You Have a Big Chunk of Your Wealth in Company Stock

First of all, consider the fact that this might not be a great idea. I've talked with investors who suffered seven-figure losses when their employer's stock turned south, and the emotional and financial impact can be devastating. It's far more likely for a single stock to have large losses than a diversified mutual fund. It's worth taking the time to figure out exactly how much you could lose—in dollars—if your company's stock suffers a significant loss. Even a stock like Microsoft MSFT, which has been a stellar long-term performer, dropped close to 63% in 2000 and 46% in 2008.

To avoid losses like that, it's wise to prune any stock holdings so they make up less than 10% of your portfolio. If you've received significant equity awards as part of your total compensation, though, it can be tough to do that without realizing hefty capital gains. If you're in that situation, there are several steps you can take to mitigate risk. First, look at the rest of your portfolio to make sure you're not doubling up on company-specific risk. If you own company stock in Microsoft, Apple AAPL, or Amazon.com AMZN, for example, you'd be getting even more exposure to those holdings if you invest in an S&P 500 index fund because those three stocks are the three biggest holdings in the index. Instead, consider investing in a different type of fund (such as a large-cap value fund) to avoid overexposure.

Sector funds are another tool you can use to reduce the risk of a concentrated stock holding. If you own company stock in the tech sector, consider adding some exposure to sector funds focusing on real estate or energy, which have historically had relatively low correlations with the tech sector and can help diversify the stock-specific risk.

Finally, a concentrated position in company stock is effectively a supercharged dose of equity exposure. So, it makes sense to reduce your total portfolio’s equity weighting from what you might otherwise target based on your age and risk tolerance.

You and Your Spouse Aren’t the Same Age

If your spouse is more than five years older or younger than you, your portfolios should probably look a bit different. The younger spouse can afford to have a higher equity weighting and a more aggressive risk profile, while the older one will want to dial back risk. If you hold assets jointly, consider using a blended approach based on the average of your two ages.

You Expect to Live Unusually Long Based on Your Health and Family History

If you’re fortunate enough to have relatives who lived into their 90s or beyond, it makes sense to plan for a longer-than-usual life expectancy. You can probably afford to take on more risk with more exposure to equities and high-risk assets. From an actuarial perspective, each year you live means your life expectancy gets longer. Some experts (such as Michael Kitces and Wade Pfau) even argue for a “reverse glide path,” which increases equity exposure as you get older instead of the reverse. This approach is geared mainly toward minimizing sequence of return risk (basically the risk of a large market downturn early in retirement) but would also help offset longevity risk. Even if you’re not comfortable increasing your portfolio’s equity exposure as you get older, though, it makes sense to increase your baseline equity allocation if there’s a chance your golden years could last longer than average.

You Have a Serious Health Problem That Makes Your Life Span Shorter Than Expected

On the flip side, if you’re dealing with a terminal illness, make sure to keep your portfolio conservative enough to meet higher-than-expected healthcare expenses and provide yourself with whatever you might need to make your remaining months and years a little more comfortable. You might want to leave a legacy to your children and grandchildren, but keep in mind that the gift of your time—not money—will probably be the most meaningful. So, don’t feel guilty about spending down your assets if you find yourself in a situation where you need to.

You’re Worried About Not Having Enough Assets to Last Throughout Your Lifetime

If you weren't able to save and invest early in your career, your portfolio balance might be relatively low. Taking a hard look at your spending is the most important step you can take in this situation. But while it might be tempting to ramp up your equity exposure to try to make up lost ground, it's more prudent to take the opposite approach because a small portfolio has less room to absorb market losses. Keep in mind, though, that it almost never makes sense to keep 100% of your assets in cash and fixed-income securities, even if your financial picture is unusually dire. Thanks to the lower correlations between equities and fixed-income securities, adding a 25% stake in equities can actually reduce volatility for a fixed-income-focused portfolio. You might also consider an immediate or deferred annuity, which can give you a guaranteed income stream and provide protection against outliving your assets.

You’re Fortunate Enough to Have a Pension or Other Stable Income Streams

Although traditional defined-benefit plans have been steadily losing ground to defined-contribution plans such as 401(k)s, more than half of all retirees still have at least some pension income. If you’re fortunate enough to be one of them, take the amount of monthly or annual income that you receive and think about how much fixed-income exposure you’d need to replace it. Because a pension is literally a fixed income, it functions like a bond position in a portfolio, so you can afford to increase the equity weighting with your other assets. Social Security works the same way: Your monthly benefits won’t grow beyond a small cost of living increase, but it’s effectively a bondlike income stream.

These are just a few of the most common cases where a one-size asset allocation doesn’t fit all. While using a model portfolio or age-based asset allocation can be a good starting point, make sure to tailor your portfolio to your specific situation to get a better fit.

The author or authors own shares in one or more securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/LUIUEVKYO2PKAIBSSAUSBVZXHI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HCVXKY35QNVZ4AHAWI2N4JWONA.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)