Indexing Outside the International-Stock Mainstream

As the investment universes become smaller, the complications increase.

Just Like Home Friday's column argued that the common international-equity index funds, such as Vanguard Total International Stock VTIAX or Fidelity International FSPSX, behave much like S&P 500 index funds. In each case, the fund's future volatility will resemble its Morningstar Category average, while over 10 years its cost advantage should push its returns near, or perhaps into, its category's top quartile.

Looking backward, both types of indexes matched their risk expectations over the past decade, but their relative returns diverged. The cheapest U.S. index funds posted top-decile gains, while the overseas index funds barely beat their category averages. This performance discrepancy, I argued, owed to a disguised small-company effect. Both flavors of index fund own somewhat larger companies than the typical actively managed fund. During that period, that stance helped U.S. indexers but hurt their international-stock rivals.

In other words, the apparent difference owed to an accident of history. There are no ongoing reasons to believe that U.S. equity indexing is "better" than doing so internationally. One may invest with equal confidence in mainstream equity index funds, regardless of whether they hold domestic or non-U.S. portfolios.

Colorful Results That's all well and good, but what about other types of international-stock indexing? When investing more broadly, as with a global index that includes the United States, or more narrowly, as with country or sector indexes, should one expect a similar pattern? Will such index funds also be roughly as risky as the competition but record relatively strong returns over time because of their lower costs?

Those questions are rhetorical--I have already run the numbers. (Prudence requires that an article's calculations precede its words.) Prior to the calculations, I had no intuition about what the results would be, other than the default belief that they would echo those of the mainstream indexes. It turned out that was not the case.

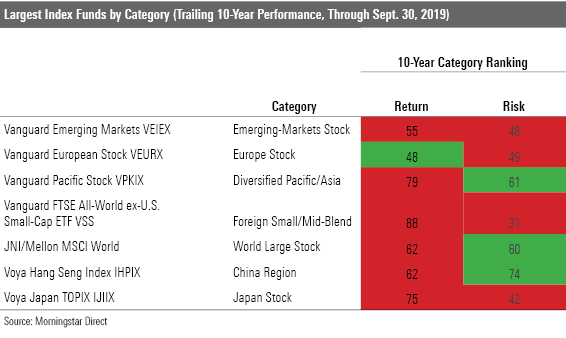

The table shows the trailing 10-year category rankings for the largest index funds that have existed over that period, for seven international-stock categories: 1) diversified emerging markets, 2) Europe stock, 3) diversified Pacific/Asia, 4) foreign small/mid-blend, 5) world large stock, 6) China region, and 7) Japan stock.

An initial note: Under Morningstar's percentile-ranking system, 1 is the best result for return, but worst for risk. That is because 1 signals the greatest amount of the measured quantity (having the most risk being decidedly unpleasant). This approach often confuses me. Thus, for our mutual benefit (or at least mine), I have color-coded the output. Green means better than the category norm, and red means worse.

The Index Funds Disappoint

That is not a pretty picture.

Once again, the index funds' risk scores meet expectations. Just as the risk percentiles for the mainstream U.S. and international-stock index funds placed roughly in their category's middle, so also do these funds. All index funds are fully invested, which increases their volatility, but most are better diversified than their actively run rivals, which dampens risk. The overall effect is neutral.

The return percentiles, unfortunately, are far from neutral. Only Vanguard European Stock VEURX snuck into its category's top half, and by the narrowest of margins. Several of the losers were outright bad. Vanguard Pacific Stock VPKIX, Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-U.S. Small-Cap ETF VSS, and VOYA Japan TOPIX IJIIX all placed in their category's bottom quartile, the exact opposite of what I assumed.

One potential explanation for these findings is that although active portfolio managers on the whole haven't succeeded at out-thinking the indexes when investing in large U.S. companies or the entire non-U.S. marketplace, they fare better when tackling other universes. Perhaps this is because they specialize. Analyzing a single region's stock markets is an easier, more manageable task than trying to master the globe.

Perhaps. But this hypothesis faces a logical difficulty. Many actively run diversified international funds are already so structured. They have regional (or even single-country) managers who select securities within those areas, thereby making the fund effectively a fund-of-regional-funds. Overall, those funds haven't especially distinguished themselves. Some have succeeded, but not enough to support the "regional expert" thesis.

Same Name, Different Paths The likelier cause is that the index funds hold substantially different portfolios than the typical active fund. Aside from the small-company effect, this does not occur with either S&P 500 funds or their foreign large-blend equivalents. Their regional weightings, country weightings, and sector exposures all closely resemble the category norms, which is why their performances can be reliably predicted. Take the category-average returns, adjust for the relative performance of smaller companies, then adjust again for the benefit of the index fund's lower expenses. The result will be an almost perfect match.

Not so with these index funds. Vanguard Pacific Stock holds 60% of its assets in Japanese stocks as opposed to 40% for the typical competitor. To cite another example, VSS invests more heavily in Canada and emerging-markets securities than its actively managed rivals. Such divergences can overcome the index fund's edge in expenses, even over long periods.

The disparities occur for two reasons. One is that defining the investment universes for the mainstream indexes is a relatively simple task (include all available securities, weighted by market capitalization), but doing so for other indexes may require arbitrary decisions. With international small-company indexes, for example, the definition of "small company" powerfully affects the index's construction.

The other reason is that as an index's investment universe becomes narrower, the odds increase that a single country, or even security, will account for a relatively large chunk of the portfolio. (Ironically, this issue also occurs with the broadest of investment universes, the entire world, as U.S. stocks account for half the globe's market capitalization.) In such cases, actively managed funds almost always underweight that position.

Friday's column delivered a firm conclusion. Today's installment, in contrast, can offer only tentative judgment. I suspect that when actively managed funds beat the lesser-known international-stock index funds over a long period, the active funds' success owes to imprecise benchmarking rather than to the managers collectively outsmarting the markets. But it's only a suspicion.

One thing I do know: These index funds require research. Investing in the major domestic and international-stock index funds is straightforward: They will go where the rest of the category goes. The same cannot be said for today's group of indexers.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WJS7WXEWB5GVXMAD4CEAM5FE4A.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NOBU6DPVYRBQPCDFK3WJ45RH3Q.png)