Time to Cash In on This Overvalued Stock

The market expects too much of Sherwin-Williams.

Sherwin-Williams SHW stands out as the highest-quality coating company we cover, but the market has saddled the shares with expectations that even a strong management team will not be able to achieve. We believe that a future input price shock is likely to unsettle the stock and lead to prices that reflect more realistic outcomes for the company. With our valuation sitting nearly 40% below the current market price, we strongly encourage investors to take any gains now.

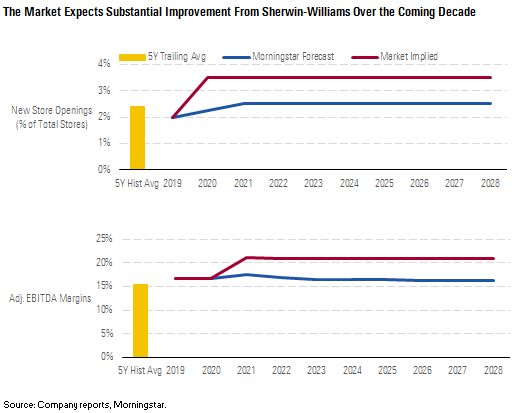

We think expectations are too high for both the top and bottom lines. Management has done an excellent job of opening new stores to seize share. However, the share price appears to assume that the company should be able to open stores even faster, even though the market is becoming more saturated with each expansion.

Investors also appear to have faith that adjusted EBITDA margins will not only surpass their highest point between 2000 and 2018 but will remain there indefinitely. We believe the expectation of a 6.5% increase in EBITDA margins off its trailing five-year base of 15.5% is unrealistic. Sherwin’s huge size provides diminishing marginal returns to scale, and the company hasn’t exhibited the pricing power over the trailing two decades to justify a forecast that rosy.

Hard-Pressed to Increase Sales Faster Than 4%-5% Over Cycle We estimate that the current market price assumes a roughly 6% sales growth rate over the coming decade. Not only has Sherwin been unable to muster a growth rate that robust in the past, but we believe falling birthrates and lower headship rates are making it even harder. We expect revenue growth to average just 4.3% through 2028: roughly 1.8% from rising same-store sales and 2.5% from Sherwin's relentless pace of opening 100 or more new stores annually.

We see three major drivers for Sherwin-Williams’ revenue growth: organic volume growth, price increases, and store expansions. Organic volume growth is largely outside Sherwin’s control, as we expect that volume will ebb and flow with the industry.

But Sherwin does control pricing and store openings. We argue that although Sherwin will be able to maintain its premium prices and therefore profit margins, there’s little evidence that it can continue to raise prices faster than the market.

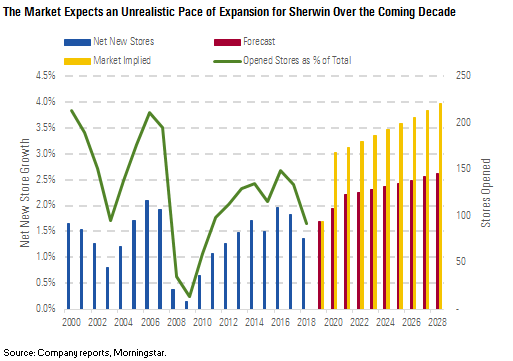

Lastly, the company relies heavily on its excellent record of opening net new locations to increase its market share and sales growth. We believe Sherwin will still be able to muster respectable growth from store openings but will fall well short of the 200 per year that will be needed to satisfy the market’s expectations.

Two factors generate organic volume growth in coatings: the consumption of more coated products and population growth. In Sherwin’s case, the bulk of its sales take place in developed markets, with a disproportionate exposure to the United States. In these countries, there’s far less opportunity for expansion, as incremental spending by consumers here go to other products and services, not necessarily coated products. This puts the onus on population growth to increase long-run volume. Unfortunately for Sherwin, population growth has slowed substantially over the past 20 years and will continue to slow over the next 10.

U.S. population growth has fallen by roughly half since 1990--from 1.2% in the early years to only 0.7%. Delayed marriage among millennials has been a key driver of falling birthrates, along with stricter immigration policies in recent years. We don’t believe either factor will be quick to reverse, meaning that total population growth will average only 0.7% over the next 10 years, not enough to support robust volume growth for the coating industry.

Outside of industry volume growth, Sherwin could grow sales through price increases. However, it faces competition across its product portfolio. The Americas group and consumer brands segments compete with Behr (Masco MAS), Benjamin Moore (Berkshire Hathaway BRK.B ), and PPG PPG. The industrial coating segment competes with PPG and Axalta. If there’s anywhere that Sherwin has pushed its competitive advantage furthest, it’s in the Americas group, where the company operates nearly 5,000 stand-alone stores that cater mostly to professional architectural painters. However, Sherwin’s prices are already far higher than peers’, and even though painters are relatively price-insensitive, that’s only true to a point--the company still needs to remain in the same ballpark as its peers.

Sherwin currently prices its products at a substantial premium to competing products. We believe much of this stems from Sherwin’s expertise in architectural, repair, and remodel products that sell to professional painters and retail customers. This expertise and the company’s sterling reputation underpin our confidence in our narrow moat and stable trend ratings.

However, we contend that although Sherwin will be able to maintain its sizable pricing spread over competitors, it will be hard to further widen margins on these products. As far back as 2000, there is little evidence that Sherwin has been able to increase prices in excess of the broader market. This means that Sherwin will be limited to inflationlike price increases over the coming 10 years. That’s well short of what we think the market price implies--above 3% annually, which seems far-fetched.

The only other growth lever under management control is new store openings. However, we think anything more than 2.5% per year in new capacity growth is unrealistic, both to us and management.

Sherwin has historically been able to expand its store footprint by about 2%-3% per year, or about 80-100 stores annually. Although we think the company will continue to gain capacity to open a larger number of net new stores over the years, today’s market price implies that the company can maintain a 3.5% new store growth rate beyond 2021.

While 3.5% may have been achievable in a few years over the past two decades, the total store base was also smaller. That translated into about 100 stores in a year. Today, that means averaging 200 new stores in a market even more saturated than it once was.

So why can’t Sherwin just open even more stores and gain more share? First, hiring good management trainees is a significant challenge. Sherwin has previously highlighted the amount of effort it takes to ramp up roughly 1,300 management trainees a year--most of whom are working in new paint stores each year. The more stores the company tries to open each year, the more it dilutes the talent pool and risks successful store openings.

Second, the company must track down suitable real estate to house its new stores in ideal locations. The U.S. paint market is saturated, and each new store needs to be carefully placed to take share or serve a local need. We think there are only so many opportunities to do this, capping annual expansion.

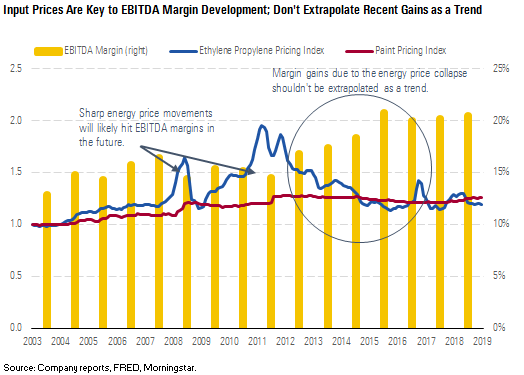

Sherwin Unlikely to Deliver Margins the Market Demands The current market price not only implies incredibly high top-line growth but EBITDA margins that will reach record highs and remain there over the economic cycle. Although cost reductions enabled by the purchase of Valspar and operating leverage in administrative overhead will provide some upside for margins, the market expects sustained levels never before seen in coatings.

Based on data as far back as 1999, we see no reason to believe that Sherwin-Williams will be able to maintain margins above previous high-water marks in both residential and industrial applications over the coming decade. Not only would Sherwin need to exceed its own high-water marks, it would also need to generate margins that exceed those of any of its competitors over the same period. We think the likelihood of this is small, even the combination with Valspar.

We forecast sustained EBITDA margins of 21% through 2028 for Sherwin’s largest segment, the Americas group, flat with 2018. In contrast, we estimate that today’s share price implies the segment will generate EBITDA margins of 27% beyond 2021. This is exceptionally optimistic.

To put the market’s 27% expectation in perspective, we have compared that number with results from PPG’s performance coating business, Akzo Nobel’s decorative paints business, and Sherwin’s legacy paint stores group. The highest recorded adjusted EBITDA margin between 1999 and 2018 was just shy of 21%, earned by Sherwin’s paint stores group in 2015 following the energy price collapse. The industrywide average over the same period was well below that, at just 14.1%.

Buying Valspar had clear benefits in the form of lower overhead cost intensity and capacity consolidation on the industrial side of the business. A large portion of the benefit from the purchase of Valspar will materialize in the industrial coating segment, where Sherwin had the most business overlap. Over the past year, management has closed six branches and will continue to adjust its footprint to maximize capacity utilization. We forecast a 1.5% increase in long-term EBITDA margins, to 16%, stemming from the benefits of the Valspar consolidation.

We estimate the market price implies that industrial coatings’ EBITDA margins will reach and remain at 20% in the long run, 5.8% higher than what it earned during its recent years of combined operation. After reviewing peer results from Akzo Nobel’s performance coating segment, Axalta’s performance coating segment, and PPG’s industrial coating segment, this margin would be among the best results ever generated in the field.

Input Price Volatility Will Eventually Hit Shares In addition to overly optimistic assumptions on growth and margins, we think the market is overlooking price volatility of key inputs. One of the biggest misconceptions in the coating industry is that these businesses resemble industrial companies that are largely unaffected by commodity price changes. However, we posit that commodity price fluctuations are a substantial driver of coating margins.

We think the recent price increases Sherwin passed to consumers will expand margins, but only so far. Over a full economic cycle, we expect fluctuating petroleum derivative and pigment prices will compress margins periodically. The next time this happens, investors may reassess their views on long-term profitability.

The single largest input in a can of paint comes from either oil or natural gas, making up almost half of the cost that goes into the product. When energy markets fluctuate, it can lead to periods of margin expansion or compression that has little to do with operational performance. For example, nearly every coating company’s margins expanded to their highest levels in 2015, not long after energy prices collapsed amid the North America shale boom. However, those margins do not persist, as mild price competition gradually erodes gains. This was true for Sherwin-Williams in 2008 and 2016. This is yet another reason we believe market expectations are overly optimistic. Energy markets are notoriously volatile, and to expect above-peak margins over the coming decade strikes us as out of touch with the history of coating companies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1d297fbb-3ca6-4b00-8c51-21e8e65e343e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/TP6GAISC4JE65KVOI3YEE34HGU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RFJBWBYYTARXBNOTU6VL4VSE4Q.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YQGRDUDPP5HGHPGKP7VCZ7EQ4E.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1d297fbb-3ca6-4b00-8c51-21e8e65e343e.jpg)