My Biggest Portfolio Mistake

Why too much of a good thing can turn bad.

The late global-health expert Hans Rosling, in his book Factfulness (which I recommend for its entertaining and statistics-based account of the ways we misapprehend our world), commented that “everything you need to survive is lethal in high doses.” The same could be said of investing. The principle of diversification is in a sense predicated on this concept: While a given asset class, sector, country, fund manager, factor, or macro theme (to name just a few ways of slicing and dicing the investment opportunity set) may offer tantalizing prospects in the here and now, load up too heavily on that idea in your portfolio and you are likely to get burned at some point.

I experienced this first-hand myself in what I consider the worst portfolio-based investing mistake I’ve made over my years as a fund investor. It was a long-gestating event, and one borne out of good intentions. Before explaining the error in full, I need to first cover a little history. It all started with Bill Miller.

When It Was Miller Time For younger investors, the name Bill Miller may not ring a bell. But if you were at all paying attention to mutual funds in the 1990s and 2000s, you're likely familiar with Miller's name and reputation. During those years, Miller was the epitome of the star manager, appearing frequently on the covers of magazines and on best-manager lists, owing to the success of his main charge, Legg Mason Value Trust. Notable, and frequently cited, was his unmatched streak of beating the S&P 500 in 15 consecutive years, from 1991 to 2005. During that time, the fund's assets grew nineteenfold to more than $19 billion from under $1 billion.

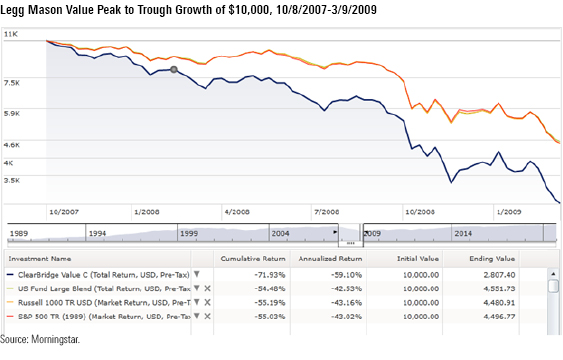

And then it all came crashing down. After earning a cumulative return of 881% during those 15 years (compared with the S&P 500’s 414% return), the fund lost its way during the 2007-09 financial crisis, incurring a 72% peak-to-trough loss from October 2007 to March 2009. While the S&P 500’s 55% loss during that period was no picnic, investors who had jumped on the Legg Mason Value bandwagon along the way with expectations that Miller possessed a kind of investment sorcery that could indefinitely defy the laws of investment gravity were sorely disappointed. They deserted the fund in droves.

The dynamics of Legg Mason Value’s rise and fall are worthy of analysis, but this particular column is not the place for that project. (Part of that analysis would certainly be the role of the media and research firms that hyped the fund, including Morningstar. While we had long been skeptical of the relevance of the so-called “streak,” our analysts nevertheless maintained a positive view of the fund throughout its bear-market travails. The fund, now called ClearBridge Value but with the same ticker, LMVTX, currently receives a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Negative.) Suffice it to say, the long climb and sudden, swift descent rivaled the most stomach-churning of amusement-park rides, and I was aboard for much of it.

From Building Block to Ticking Clock I was fortunate to begin investing money with Bill Miller in the early 1990s, long before he became the toast of the town. A somewhat accidental confluence of factors led to this circumstance. When I graduated from college, my grandparents gifted me with some money, along with a referral to a Legg Mason broker. A short time later, I began work as a junior mutual fund analyst at Morningstar, where I encountered Miller and his fund, not long after he took over the fund full-time. Whereas the previous was a traditional value manager, heavy on industrials and financials, Miller fashioned himself as a new kind of value manager, with a more capacious definition of what kind of company could be considered a "value" pick. Moreover, during a period when most fund managers wrote formulaic, uninformative investor letters, Miller penned long, wide-ranging letters that drew on his background in philosophy and fascination with all manner of ideas. I was smitten and soon used that Legg Mason broker to invest a chunk of my savings in Legg Mason Value. Down the road, as my finances permitted, I added more.

For many years that was a great call, as I benefited from Miller’s outperformance and the power of compounding. But this success was simultaneously sowing the seeds of its eventual undoing. Because as Legg Mason Value grew in size, it came to dwarf every other holding in my portfolio. And, not wanting to take assets away from Miller, I amplified this effect by selling off other, lesser-performing funds when I needed to produce cash (when we made a down payment on our first home, for example). Other concerns weighed on me as well, such as the heavy capital gains taxes I’d inevitably owe on any transaction.

You can see where this is heading. By the time markets started to head south in 2007, Legg Mason Value constituted a significant majority of my taxable invested assets. I was and remain a committed long-term investor who does not believe in market-timing, and I wasn’t about to sell off into a declining market. And it’s not as though volatility was foreign to Miller’s strategy; it had always been a more concentrated and volatile fund than its peers, and I felt Miller had earned the benefit of the doubt. So I could only watch in horror as the fund’s value plummeted by nearly three fourths during the financial crisis.

The fund rebounded with a big bounce in 2009, and I waited that out, but it takes a long, long time to break even after such a steep drop. Eventually I made the difficult decision to sell out of the fund over the course of 2010, deploying the assets into a far more diversified portfolio, spread across multiple funds, investment styles, and regions. (In contrast with my taxable account, I’d always invested my retirement accounts in a highly diversified portfolio of investments.) I had long tolerated the fund’s high expenses because of the performance, but now that my overall capital gains exposure was lower, and with the availability of other loss carryforwards to put to use, I decided it was best to make a clean break. Moreover, the announcement that Legg Mason was adding a comanager to the fund signaled that changes would be coming to the portfolio and that Miller’s reign at the fund was not indefinite.

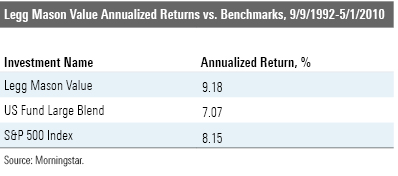

Lessons Learned You could argue that, in the end, even with the bear-market losses, I still came out ahead compared with investing in, say, an S&P 500 fund over the entire tenure of my ownership. And that's probably true, though the 1% annualized difference is likely slimmed even further when you take into account the tax effect of capital gains distributions, which were likely significant over time. Regardless of the return difference, however, I patently did not enjoy the experience of seeing my taxable portfolio lose so much value and would not want to repeat it. So where did I go wrong, and what are the broader lessons learned?

I don’t think that my biggest mistakes came at the beginning or end. Early on, my total wealth largely resided in my human capital, and I had significant risk capacity to warrant holding concentrated, actively managed funds. Near the end of the cycle, trying to market-time a sale of the fund both would have violated my own long-term philosophy and risked sitting out the eventual bounce that the fund experienced.

Where I do think I erred is in not updating my assumptions after I had owned the fund for a decade. When I started investing, my goals were largely amorphous--I just wanted to accumulate wealth via the stock market. By the time I was in my early 30s, with two young children, I had more-concrete goals--buying a house, saving for eventual college educations--that made a concentrated position in a risky fund even less appropriate. Moreover, I did not fully appreciate the extent to which style, concentration, and price risks were embedded in the fund’s strategy--and in turn my portfolio. Finally, I allowed inertia to take over to an unhealthy degree. I do think that a hands-off approach has value--responding to short-term market fluctuations is not a winning approach--but benign neglect is benign for only so long. During that period, I should have begun to gradually divest assets from the fund into a more diversified portfolio, perhaps over a period of a year or two.

Although chastened by my experience, I was not turned away from active managers, in whom I continue to invest. But I am much more cognizant of their risks and downsides, and I prefer now to mix active managers with indexed exposures. Moreover, I am alert to the tax consequences of holding active managers in a taxable account, as capital gains can be a hidden cost to an investor’s bottom line and can create skewed incentives in holding on to a fund.

Ultimately, my experience with Legg Mason Value reflects the importance of rebalancing and of maintaining exposure to a broad sampling of asset classes, investment styles, and sectors. Any given market segment (or individual manager) can outperform for a sustained period (U.S. large-cap growth’s current run comes to mind), but when momentum shifts, it often does so to the downside in pronouncedly unpleasant ways. I know that I won’t allow myself to get charmed in that way again.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2e13370a-bbfe-4142-bc61-d08beec5fd8c.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RYIQ2SKRKNCENPDOV5MK5TH5NY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6NPXWNF2RNA7ZGPY5VF7JT4YC4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2e13370a-bbfe-4142-bc61-d08beec5fd8c.jpg)