3 Myths About Sustainable Funds

Sustainable funds perform on par with traditional funds, cost about the same, and offer plenty of choice.

Individual investors continue to express significant interest in sustainable investing, but they often run into a brick wall when they discuss the topic with their consultants or financial advisors.

In a 2017 Nuveen survey of investors, four out of five said they want their investments to make a positive impact on society and on environmental sustainability. And in an Allianz Life survey released in April, two thirds of millennials and half of generation Xers and baby boomers said they would be specifically interested in having some money in environmental, social, and governance investments.

When they make inquiries to trusted investment intermediaries, however, they often get what I call “the wave-off.” That’s when the intermediary waves his hand (and it’s usually a he) and says, “Sustainable investing? Nah, you don’t wanna do that.”

Why not? When it comes to fund investing, the intermediary wave-off is often backed by these three myths:

The Underperformance Myth The most persistent myth about sustainable investing is that it leads to underperformance. The theoretical basis for this myth is that any time you limit your investable universe for nonfinancial reasons, you increase tracking error and risk underperformance. In the context of sustainable investing, this myth stems from the practice of excluding certain stocks based on the products a company makes. It gained credence in an era when tobacco exclusions were common in what were then called socially responsible investing funds and tobacco stocks outperformed. There are three major problems with the claim of underperformance:

First, tracking error implies performance will differ from a benchmark, not that it will lag a benchmark. GMO's Jeremy Grantham demonstrated this by looking at how investment portfolios are affected by divesting from entire sectors, comparing the S&P 500 with portfolios that excluded each of the benchmark's 10 sectors. He found that, from 1989-2017, the portfolios' returns were within about 50 basis points of each other, with six finishing above and four below the index return.

Excluding tobacco stocks may have contributed to underperformance in the 1990s and early 2000s, but over the past decade their absence would have contributed to outperformance. The MSCI World Tobacco Index has gained 8.6% annualized for the 10 years ended Aug. 31, which lags the MSCI World Index’s 9.2% annualized return.

Second, exclusions are not the primary focus of most sustainable funds today. Many still use some exclusions, but for most, the real focus is on integrating the consideration of environmental, social, and corporate governance criteria into their investment process and engaging with companies they own to encourage better ESG performance.

Third, the bulk of academic research into the actual performance of sustainable investment portfolios has shown no performance penalty associated with this type of investing, and, if anything, the findings tilt toward positive risk-adjusted performance rather than negative, as I outlined here.

Morgan Stanley just published a study of sustainable fund performance using Morningstar data going back to 2004. It found no difference in the returns of sustainable funds and traditional funds over that overall time period and only three calendar years when returns were significantly different. Sustainable funds underperformed in 2004 and 2010 and outperformed (by a lot) in 2017.

But when Morgan Stanley took risk into account, the picture changed dramatically. Sustainable funds demonstrated a 20% smaller downside deviation consistently over time. In 14 of the past 15 calendar years, sustainable funds had significantly lower downside deviation than traditional funds.

All sustainable investment strategies are not alike. Some mix exclusions with ESG integration, others focus only on the latter. Some pursue specific investment themes and try to generate a kind of social or environmental impact. Many also actively engage with companies to improve corporate ESG practices. They also differ in their structure (active/passive) and investment style (value/growth). And there is a range of manager skill and overall fund quality that investors must assess when selecting funds, just as they must do when working within the traditional fund universe. But there is no reason, based on generalizations about performance, to steer investors away from populating their portfolios with sustainable funds.

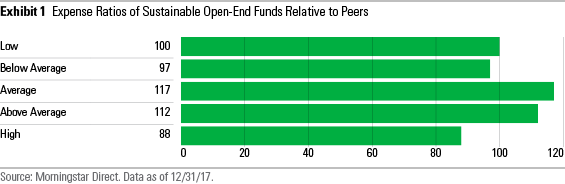

The High-Expenses Myth Another common refrain I hear from advisors and analysts is that sustainable funds tend to be expensive. This myth got started around the turn of the century when many SRI funds were run by small asset managers that charged higher fees. At the end of 2017, I looked at the expense ratios of all U.S. sustainable open-end funds compared with their peers. Within each fund category, Morningstar groups expense ratios from Low to High. I found that sustainable funds' expense ratios were evenly distributed from Low to High. In fact, 199 share classes were grouped in the Low or Below Average expense buckets, 117 in the Average bucket, and 200 in the Above Average or High expense buckets.

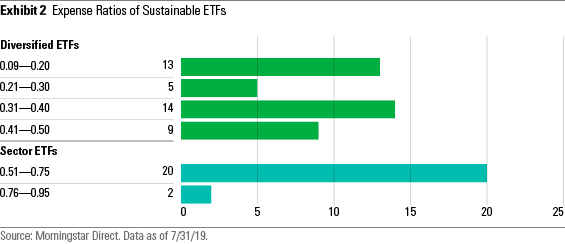

The expense ratios of sustainable exchange-traded funds have been falling. As recently as 2016, the only two diversified ESG ETFs cost 50 basis points, but today, nearly all of the now more than 40 such ETFs have lower expense ratios. In fact, 13 charge between 9 and 20 basis points. It’s hard to compete with market-cap-weighted index ETFs that have rock-bottom expense ratios, but these are certainly in the ballpark.

The Not-Enough-Choice Myth

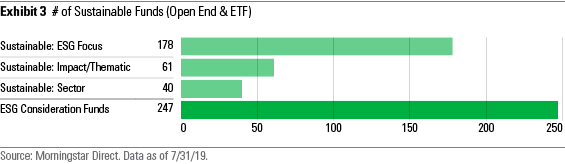

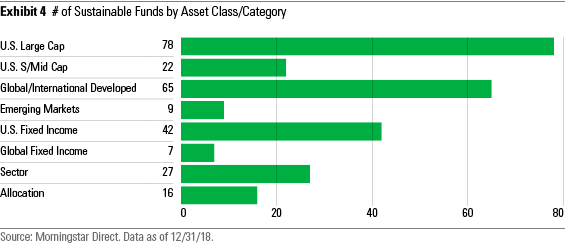

When it comes to building a portfolio, the rap on sustainable investing is that there aren’t enough choices. But my research indicates that, as of midyear, there were 279 sustainable open-end and exchange-traded funds available to U.S. investors. Another 247 funds have recently added ESG criteria to their prospectuses. That’s more than 500 choices that form a viable universe from which to build diversified portfolios of stocks and bonds.

Investors can find sustainable funds in 65 Morningstar Categories, with plenty of viable choices in the mainstay categories for most portfolios: U.S. equity, non-U.S. equity, and investment-grade bond.

To summarize, sustainable funds, as a group, don’t underperform; they aren’t too expensive; and there are plenty of choices available to use in building sustainable fund portfolios. Understanding these claims as myths can go a long way toward helping those interested in sustainability embed it in their investments.

Interested in ESG? Check out a curated collection of our latest content on ESG investing.

Jon Hale has been researching the fund industry since 1995. He is Morningstar’s director of ESG research for the Americas and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. While Morningstar typically agrees with the views Jon expresses on ESG matters, they represent his own views.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/42c1ea94-d6c0-4bf1-a767-7f56026627df.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/42c1ea94-d6c0-4bf1-a767-7f56026627df.jpg)