Fine-Tuning Your U.S. Equity Fund Portfolio

Let the Morningstar Style Box be your guide.

Do your U.S. stock funds provide you the kind of exposure to which you aspire?

In my initial column, which covered minimizing clutter in your mutual fund portfolio, I flagged several topics for future consideration. Today, I’ll pick up the threads of one of those topics, namely, how to fine-tune your allocation to U.S. equities. Most U.S. investors hold the majority of their stock portfolios in domestic stocks, so it’s important to keep your eye on the ball in this portion of your portfolio.

I say “fine-tune” rather than “optimize,” because I don’t think you have to approach these issues from a totally scientific or quantitative perspective. (Certainly, there are tools and services available that can provide you with that kind of calibrated portfolio optimization, though even such algorithmic apparatuses may offer a false sense of precision.) Rather, it’s more important to make sure that you are, broadly speaking, getting things right.

I use the Morningstar Style Box as a guide here. The style box has often been subject to criticism, typically from fund managers who feel they’ve been hemmed in by its grids. The style box is not perfect; definitions and cut-offs for what constitutes small versus mid, value versus core, and so on, are always going to be fluid (that’s by design) and subject to different interpretations. Nor was the style box ever intended as a prescriptive tool. Rather, it is best thought of as a descriptive tool to give you better insight into the more granular characteristics of your fund portfolios.

I will break down the process of getting your U.S. allocations right into three key steps: determining your objectives; matching your funds’ actual investment approaches to those objectives; and keeping up with changes. Let’s tackle those one by one.

Step 1: Determine Your Objectives As with any aspect of financial planning, it helps to first ask yourself what your objectives are, in this case particularly with respect to your U.S. equity allocations. Do you want to stay very close to what the rest of the market looks like, or do you want to incorporate your own preferences and viewpoints into your allocations? Is your tolerance for risk higher than the norm, and do you prefer to invest in smaller companies with big potential growth prospects (which might cause you to lean toward small caps and growth stocks)? Or are you more of a contrarian, preferring managers who look for a bargain (which might indicate a tilt toward value stocks)? Are there certain industries or sectors that you have a particularly strong belief in or affinity for? Alternatively, are there industries you would prefer to downplay--for example, you work in the healthcare industry so would prefer to downplay its importance in your portfolio because so much of your financial wherewithal (your salary) is riding on it?

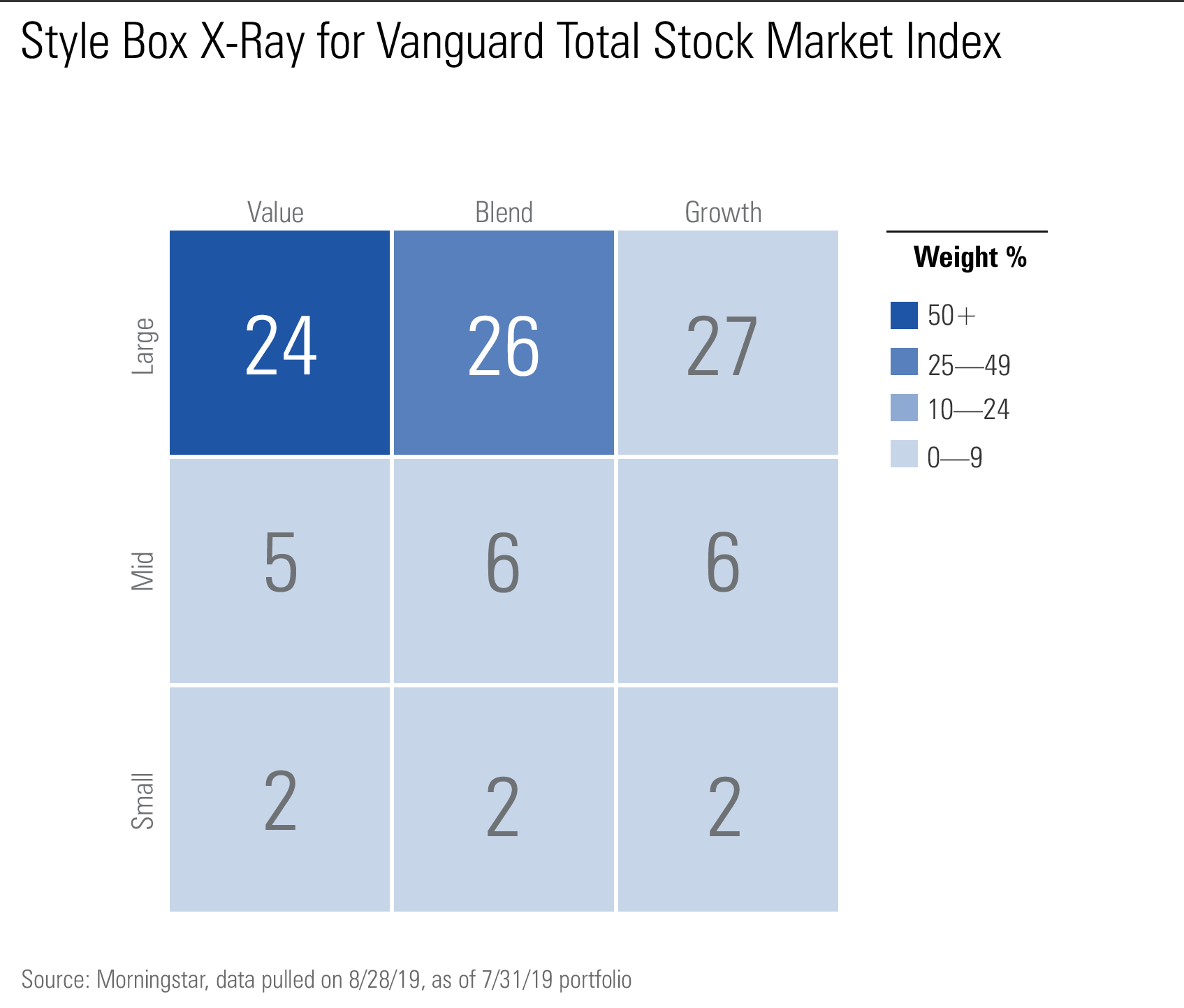

It will help to have a baseline notion of what the market looks like. Below is a style box X-ray of the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index VTSAX fund, which follows a market-cap-weighted index of the full U.S. stock market. You can see that about three fourths of the portfolio is distributed evenly across the large-cap value, core, and growth segments of the style box, with 17% in mid-caps and only 6% in small caps also spread across the value-growth spectrum.

Consider this your starting point. You can easily match the market through an index fund, a perfectly acceptable, low-cost, and easy-to-maintain approach. If you want to incorporate your tendencies and preferences, as well as active managers, there are various ways of thinking about your allocations. You could keep the size elements in place (round the numbers to a 75%/15%/10% mix) but skew your style distributions. Conversely, you could be style-neutral but take a bigger bet on small caps if you have a stronger appetite for volatility and a long time horizon. We would not recommend relying too much on your gut instincts (those can lead down treacherous behavioral paths), but academic research has demonstrated long-term edges to small-cap and value approaches, so it might be worthwhile to build in something of a tilt to these styles, for example.

From a philosophical perspective, when helping employers build fund lineups for their retirement plans, the manager selection team at Morningstar believes that participants should have access to a full spectrum of small to large and value to growth, but we aren’t dogmatic about it. We would not recommend that a plan offer funds from every style box category, and that would likely be overkill for an individual investor as well, because there ends up being considerable overlap between funds. At the same time, it’s probably not wise to get excessively skewed in one direction or another. The market tends to move in cycles, and while it’s true, for example, that growth has significantly outperformed value over the past decade, in the past value has surpassed growth, and it seems unlikely that growth’s advantage can carry on indefinitely. Our preference is to include relatively style-pure funds because those enable retirement investors to target their exposures and rebalance more efficiently.

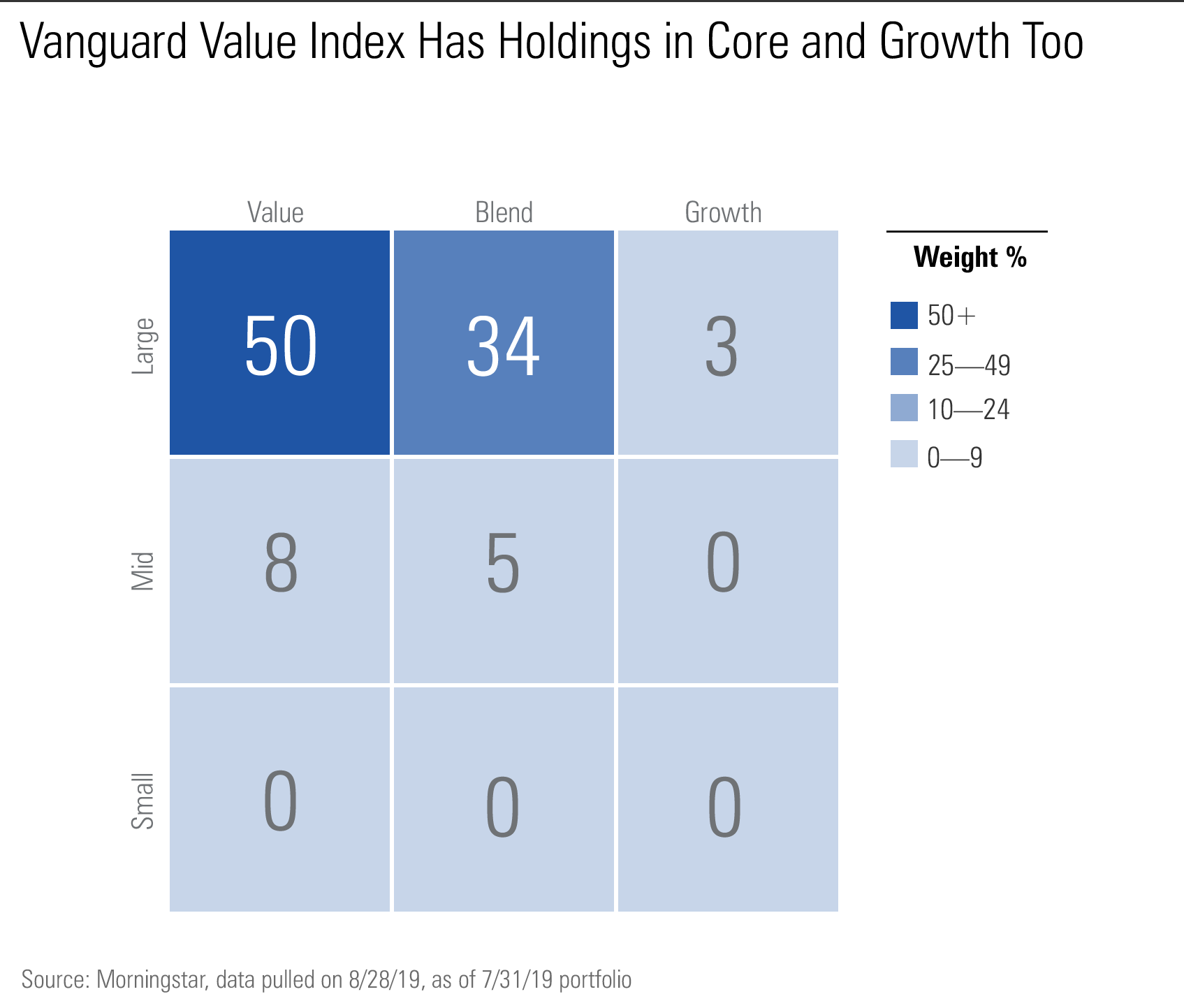

Step 2: Identifying the Right Investments The wrinkle to fine-tuning your portfolio is that you can't simply rely on a fund's name, or even its Morningstar Category, to fully guide you. In actuality, it's the rare fund that is "style-pure." Even Vanguard Value Index VVIAX (categorized as large value by Morningstar) has only 58% of its portfolio in stocks classified as value by the style box definitions.

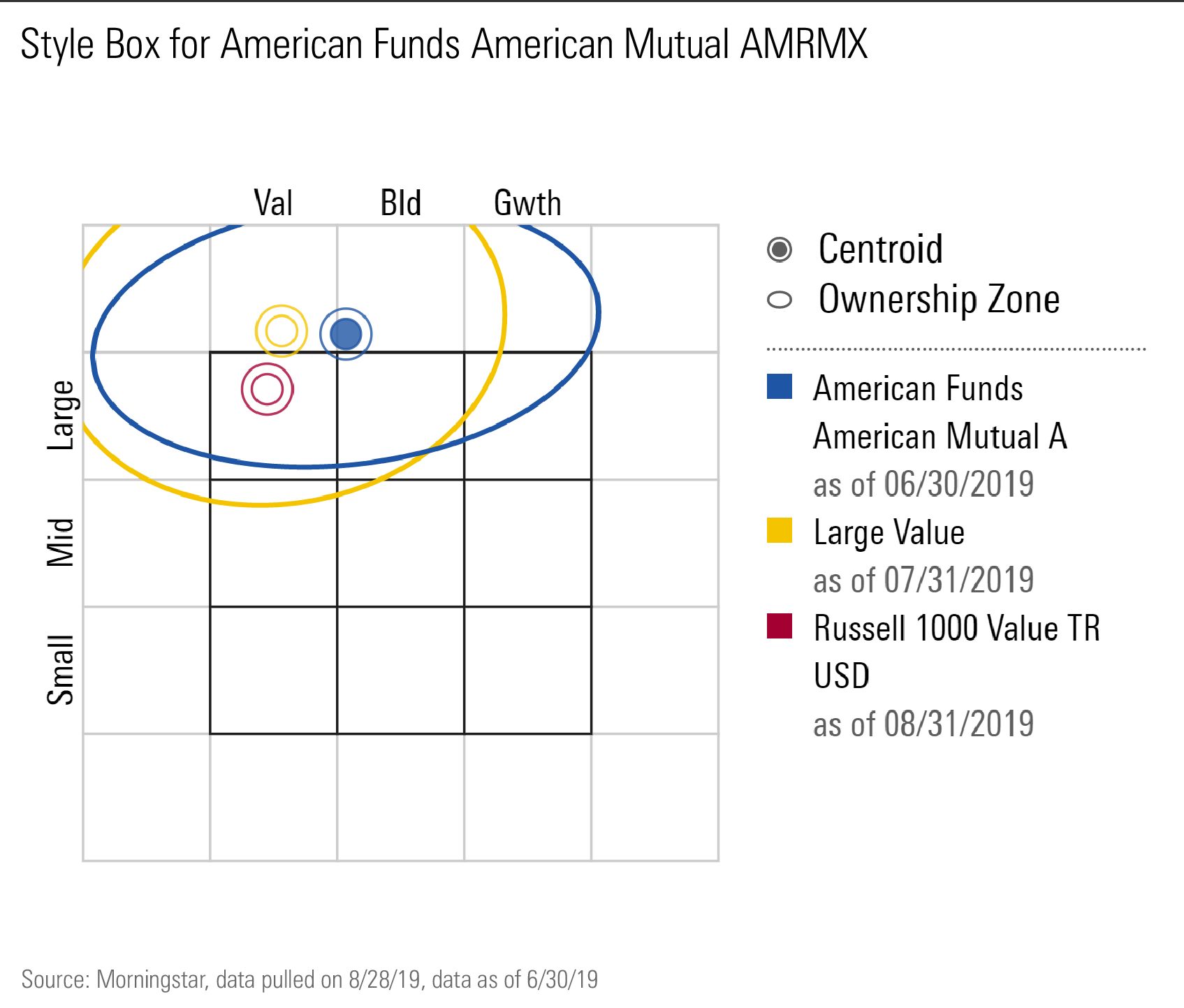

Indeed, even within the large-value category, there’s a wide range of approaches. Deep-value quant fund LSV Value Equity LVAEX has 78% of holdings classified as value, whereas the popular American Funds American Mutual AMRMX lands only 33% of holdings in the value column, owing to its focus on mega-cap, high-quality, dividend-paying stocks, some of which land in the blend or even the growth columns of the style box. The same kinds of variances exist within the growth and small-cap categories.

A couple of points to emphasize here. First, it’s not a bad thing that we find such a range of portfolios among actively managed funds in a given category; we should not want or expect homogeneity from active managers (though we often find it anyway), and the definitions of what constitutes value or growth (or other investment styles) are not fixed or universally agreed upon. Second, it’s also OK to own funds that aren’t perfect fits for their category, as well as those that are “purer” versions of a category’s style. The key is to be aware of what approaches your funds take and to not let unintended biases infiltrate your portfolio.

How to stay on top of these details in your portfolio? For one thing, you can look at the style box for any fund in the Portfolio section of its Quicktake on Morningstar.com. While it won’t give you the percentage of holdings in each part of the style box (as in the examples I’ve included above), it will show you where the fund plots in the style box and the range of its holdings. In the example below, for example, you can see that American Funds American Mutual plots right on the border of value and core, while its holdings (represented by the blue elliptical loop) extend into core and even growth.

Even more useful is to pair the individual fund snapshots with an X-ray of your entire portfolio. Doing so will give you a bird's-eye view of where any portfolio imbalances lie, and then you can use the individual style boxes to target the specific areas you may need to tailor. While doing this exercise, you may discover that you are comfortable with your allocations, even if they aren't perfectly aligned with your targets, but if you haven't checked in a while, you might be surprised by how far things have drifted.

Step 3: Developing a Plan for Change Your portfolio will evolve over time, even if you do nothing to touch it, due to both individual fund performance patterns and larger market trends. One of the most notable such trends over the past decade-plus has been the divergence between growth and value in U.S. equities. The reasons for that split and thoughts for how to deal with it as an investor are topics for another column. (Ben Johnson addressed the value side of the equation in a helpful article earlier this year.) But say you'd invested $10,000 apiece in Vanguard Value Index and Vanguard Growth Index VIGAX in August 2006 (identified by Ben as the turning point in the value/growth saga). You'd be sitting today with about $24,000 in the large value fund and $37,000 in the large-growth fund. You'd have made a nice return, to be sure, but instead of having half your assets in each fund, the split would now be 40%/60%.

Growth’s superiority over value during this period is unusual, to say the least, and the investor who did not rebalance would have benefited. But in more-normalized periods, the market leaders tend to shift around more frequently, and from a portfolio perspective, there is a disadvantage in that the investor’s allocations no longer represent the original intentions. There’s nothing wrong with “letting winners ride” up to a certain point, but investors should consider setting thresholds for when they will rebalance and enshrining those trigger points in their personal investment policy statements. You might even take a graduated approach--for example, if allocations get 10 percentage points out of whack, dialing them back to a 5-percentage-point deviation--to lessen the impact.

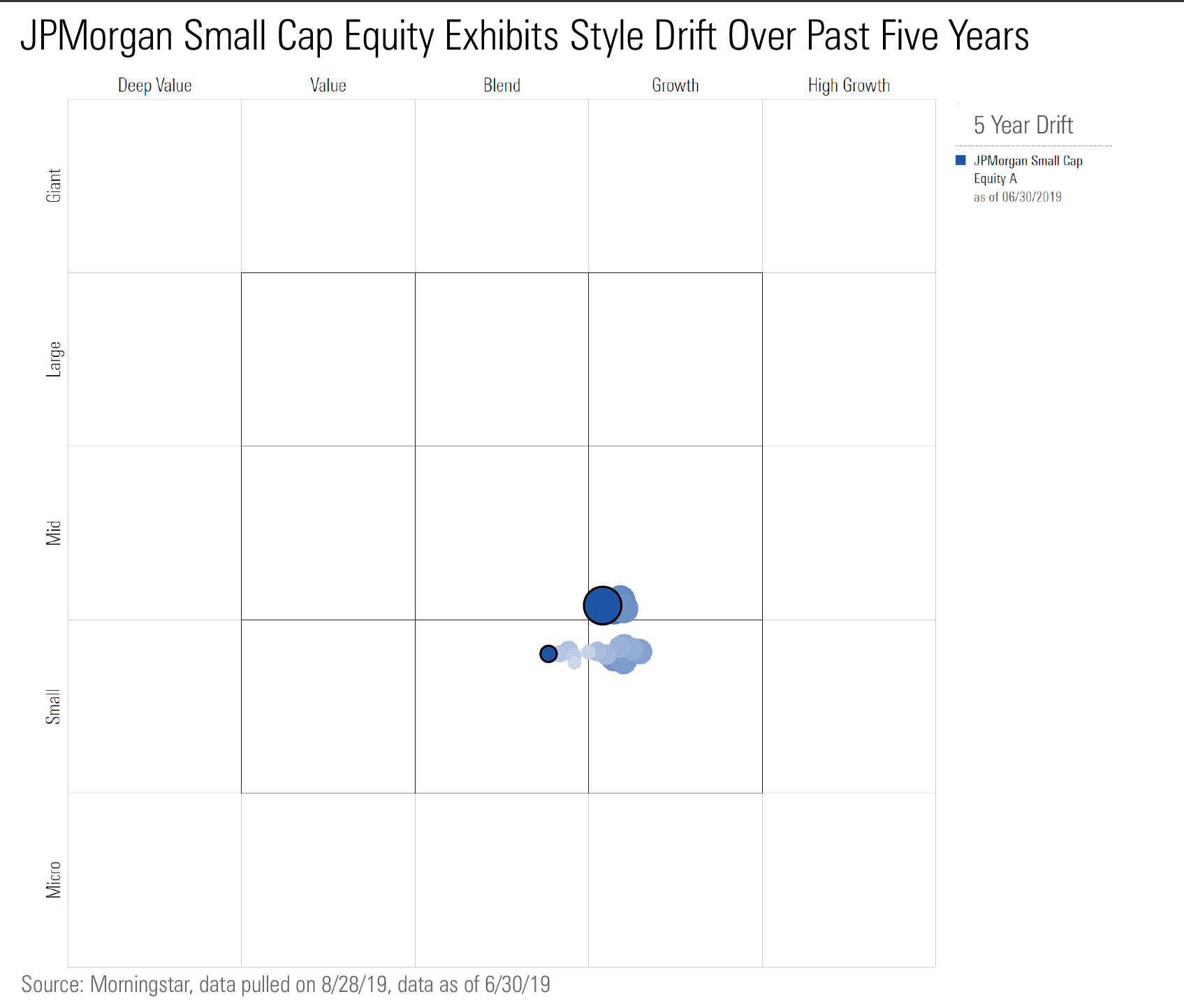

Another point to keep in mind about style shift is that funds themselves can change over time. This can happen for a host of reasons (a topic I intend to explore in a separate column), such as a change in management team, a change in philosophy, a transformed opportunity set, or constraints that develop as a fund grows larger, among other factors. The style trail chart below, for instance, shows how JPMorgan Small Cap Equity VSEAX, which has a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Silver, has shifted over the past five years from the small-cap core portion of the style box (represented by the small black circle) into the mid-cap growth square (the large circle). A gradual shift is likely not a reason to question your ownership of the fund, but it should occasion an reexamination your overall allocations.

The key principles to keep in mind when rejiggering your U.S. equity allocations are those we started with: a) remaining aware of your actual underlying exposures and b) ensuring that any skews are aligned with your objectives, preferences, and risk characteristics.

A Final Note on Free-Range Funds Some funds don't fit neatly into any style box categories. While the fund world has moved toward more tightly constrained investment mandates, iconoclastic, go-anywhere managers remain in the landscape. An example might be the once-booming and highly rated Fairholme FAIRX (it now receives a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Negative), run by Bruce Berkowitz, whose concentrated and hard-to-label strategy gets placed in the large-value Morningstar Category but displays a current equity investment style of small-growth. (A minority of the fund's portfolio is even in straight equities these days.)

A fund like this could play havoc with your more carefully calibrated equity exposures. One suggestion would be to place such funds in their own bucket and to make sure that bucket’s allocation is limited to an appropriate risk tolerance level within your overall portfolio. You’d still want to periodically check how the underlying holdings affect your overall style and size skew, but they would effectively be bracketed off as almost a separate asset class in your portfolio. Think of it as the free-range section of your otherwise orderly agricultural enterprise.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2e13370a-bbfe-4142-bc61-d08beec5fd8c.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2e13370a-bbfe-4142-bc61-d08beec5fd8c.jpg)