Unraveling Foreign Dividends

Bigger yields require patience.

A version of this article previously appeared in the June 2019 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor.

Foreign stocks might look enticing to income-oriented investors. As of this writing, foreign-stock mutual funds and exchange-traded funds offer higher yields than U.S.-stock funds. But pocketing those dividends takes some effort. The portfolio managers of foreign-stock funds must navigate irregular payment schedules and a web of tax treaties to deliver those dividends to shareholders. Fortunately, well-equipped managers are up to the task. Investors need to exercise patience, as the frequency and magnitude of dividend payouts from foreign-stock funds tend to be less consistent than for U.S.-stock funds.

The Groundwork ETFs and traditional open-end mutual funds act like pass-through vehicles for dividend payments. These funds collect the dividends distributed by their underlying stocks, then pass them along to shareholders.

The Investment Company Act of 1940 requires that funds distribute at least 98% of their ordinary income (dividends) to shareholders. Beyond that, fund providers have some flexibility when scheduling these payments. They can distribute dividends throughout the year across several installments or make a single lump-sum payout.

Quarterly dividend payments are the norm for U.S. corporations, and many U.S.-stock index-tracking funds follow suit. While the exact payment dates can differ from fund to fund, dividend payments are often made to shareholders near the end of March, June, September, and December. Furthermore, U.S. corporations often loathe cutting dividends, so their quarterly payments typically remain relatively consistent, despite fluctuating earnings. That consistency shows up in the quarterly payments made by U.S.-stock index funds.

Exhibit 1 shows the quarterly dividend payments made by Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF VTI for the three years through December 2018. Similar index funds like Schwab U.S. Broad Market ETF SCHB, iShares Core S&P Total U.S. Stock Market ETF ITOT, and SPDR Portfolio Total Stock Market ETF SPTM follow similar quarterly payment schedules.

But foreign-stock funds have different payment schedules, and the magnitude of those payments can vary substantially from one distribution to the next. Foreign-stock ETFs from Schwab, BlackRock (iShares), and State Street pay dividends twice per year. They typically make a small distribution in the middle of the year, followed by a considerably larger payment at the end of December.

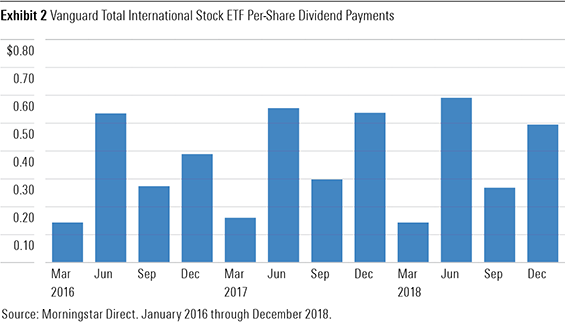

Vanguard's foreign-stock funds are more easily compared with U.S. stock funds because they distribute dividends each quarter. Exhibit 2 shows the quarterly per-share dividend payments for Vanguard Total International Stock ETF VXUS. While it pays out quarterly, the size of those payments changes quarter to quarter. VXUS pays out relatively small amounts in March and September, with larger distributions in June and December.

So, what's causing the difference in payment frequency and magnitude?

Fits and Spurts In a certain way, the lumpy dividend payments made by foreign-stock funds reflect the dividends paid by individual foreign stocks. While some overseas corporations make quarterly dividend payments, a large fraction do not. Many make semiannual distributions, while others pay out only once per year. Furthermore, these payments are seasonal.

Many European companies pay dividends between March and June. Some companies, like Nestle, Allianz, and Novo Nordisk make only a single annual distribution during this time, while others may make a second smaller payment later in the year. Most Japanese companies make regular semiannual payments in June and December.

The timing of the actual receipt of those payments leads to another difference between U.S. and foreign dividends. Whether in the United States or abroad, dividend-paying companies will outline both a dividend record date and dividend payment date. The record date is used to identify shareholders that will receive the dividend, while the payment date dictates when cash will actually hit their accounts.

Thus, there's a delay between these two dates. Overall, U.S. companies generally make payments in a timely fashion. The vast majority of S&P 500 companies distribute dividends within one month of identifying the shareholders they owe.

Some foreign companies pay out quickly. Corporations like Nestle, Total, and Anheuser-Busch InBev make their actual payments only one or two days after their record date. Other companies, including HSBC, Vodafone, and Nintendo, may not actually pay until months after their record date (Japanese firms in particular often take two to three months to fulfill their payments). Collectively, this adds another layer of variability to the income stream that foreign-stock funds experience and delays receipt of cash.

Foreign tax withholding is the third difference between U.S. and foreign dividends. Foreign companies withhold some of the cash owed to U.S. investors to pay taxes on those dividends. And these tax rates can be rather punitive. Countries like Germany, Switzerland, and Australia can levy institutional tax rates on dividends of 30% or more.

Fortunately, the U.S. has tax treaties in place with many foreign governments, reducing the tax rate for U.S. investors. However, fund providers must actively pursue the difference between the withholding (1) and treaty (2) rates, as foreign governments aren't anxious to part with tax revenue. The time required to reclaim these taxes can vary by jurisdiction and circumstances. In some cases, it can take years before a fund is able to claw back the cash it is owed. In these situations, the amount that is reclaimed gets distributed to shareholders after it is received.

Collect Then Distribute While a fund may be owed cash, whether from gaps between record and pay dates or claims on taxes, it often isn't prudent to make a distribution until the cash is in hand. Paying dividends before cash has been received can potentially cause a fund to distribute more than it has taken in over the course of a year should those payments not materialize. In this situation, portfolio managers will have to issue a return-of-capital distribution to make up for the difference, which can have adverse tax consequences.

A return-of-capital distribution itself isn't taxable. However, it lowers investors' cost basis in the fund, which increases the capital gains due when they eventually sell their shares. In short, portfolio managers prefer to avoid a return of capital because it increases shareholders' tax burden. A return of capital also lowers the asset base on which the fund provider can levy the fund's expense ratio, which leads to less revenue. Fewer dividend payments and smaller payouts earlier in the year provide foreign-stock funds with more time to collect dividend payments before passing them along to investors, thus dodging excessive payouts and a potential return of capital.

There is no right or wrong way for a foreign-stock fund to structure its dividend distributions. The differences in payout frequency and magnitude between U.S. and foreign-stock funds are a response by fund providers to deal with a variable stream of dividend payments, while simultaneously avoiding adverse tax consequences for shareholders. And different providers use different distribution schedules. Foreign-stock fund investors should be aware that these differences have an impact on how and when they receive their dividends. They won't arrive in a steady manner every quarter like those from U.S.-stock funds.

By law, funds will distribute almost all (98% or more) of the dividends they have received. Therefore, funds that track similar indexes should provide comparable yields in any given year. Exhibit 4 lists six foreign-stock ETFs and their trailing-12-month yield as a function of their closing price on Dec. 31, 2018. The small differences in yield across these funds are caused by the differences in dividends received. Differences in country and regional weightings also contribute to small deviations in yield, as each fund is tracking a slightly different benchmark. All of these funds feature a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Gold or Silver and low expense ratios, and are worth considering as a long-term core component of a diversified portfolio.

1) MSCI. 2019. "MSCI Index Calculation Methodology." https://www.msci.com/eqb/methodology/meth_docs/MSCI_IndexCalcMethodology_Apr2019.pdf.

2) United States Internal Revenue Service. 2019. United States Income Tax Treaties--A to Z. https://www.irs.gov/businesses/international-businesses/united-states-income-tax-treaties-a-to-z.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)