How Did 529 Plans Become So Confusing?

An accident of history leads to opportunities and challenges for parents saving for college.

The tax code is the bamboo grove of U.S. policy. Policymakers plant provisions here and there, but they quickly grow out of control and form a tangled mess. A small tax incentive goes in, becomes popular, and quickly gets expanded; it then takes on a life of its own, even if it is not really helping to achieve the policymaker’s original aim.

This story is particularly true for 529 plans because they were created with even less thought than the typical tax preference. Further, the implementation of 529 plans is left up to the states, creating an even more confusing mess than other tax incentives. In fact, the 529 plan was created to accommodate Michigan’s prepaid tuition plan, and then it was expanded through legislation in 1996 and 2001 into the system we have today.

Parents saving for children’s educations can put aftertax money into these plans, watch it grow tax-free, and then take it out tax-free to pay for qualified expenses. So far, so good--or at least defensible. 529 plans, from a federal tax perspective, look like Roth IRAs for higher education, albeit with much higher contribution limits. From a saver’s perspective, this makes sense. (Others can debate whether this is a great use of a federal subsidy or not, and there are reasonable arguments on all sides.)

The Confusion Begins When 529s Move Beyond Prepaid Plans

Because 529 plans were designed to facilitate prepaid tuition plans, states continued to play a critical role, expanding the offerings to include a version with an investment lineup and the ability to use the funds for any higher-education expenses, which quickly overtook prepaid plans in popularity and net assets. States could open these plans to anyone looking to save for college, and some states, such as Alaska and Nevada, realized early in the last decade that they could become the preferred place for out-of-state savers. They worked with established asset managers to set up high-quality 529s that are often advertised without any mention of the state’s role.

Fast-forward to today, and parents can choose from hundreds of 529 options run by 49 states and the District of Columbia. Not only does this complexity confuse people trying to save for college but it is also far from clear why states should be managing investments for college. A prepaid tuition plan for a state university is one thing, but state governments are not generally in the business of picking investments for ordinary people, except for their state employee retirement plans.

Some state plans are good, some are bad, and some are a mix of good and bad. But most children (about 90%) are not fortunate enough to live a state with a best-in-class 529 plan with a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Gold. Instead of making it easy for people to find the best investments, states tend to market their own plans to their residents.

Throwing State Income Tax Incentives into the Mix Can Make Bad Plans Appealing

Most confusingly, states then started to add state income tax incentives to invest in their 529 plans. Sometimes these incentives were available even for savings outside of state, but mostly they were designed to direct savings to a 529 plan in-state. This patchwork of incentives has created the biggest problem with 529 plans.

Simply put, the allure of tax incentives may lead savers to subpar plans.

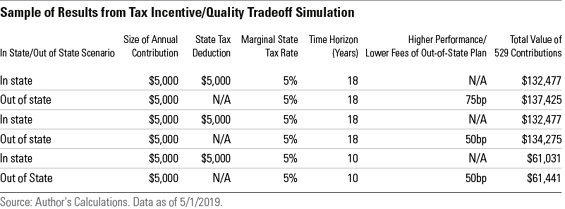

The table below illustrates this by comparing the impact of a higher-quality, out-of-state plan with a more expensive in-state plan with tax benefits. In this example, we consider a hypothetical household facing a 5% marginal tax rate and living in a state that offers a $5,000 deduction on state income taxes for 529 contributions.

This example shows that it can be advantageous to forgo in-state tax benefits in favor of investing in high-quality, out-of-state 529 plans--at least if this household starts saving early enough. For the many who live in states that do not offer the best 529 plans, out-of-state plans can allow stronger performance, lower fees, or both to compound over time. However, because tax credits often encourage 529 savers to keep their money in the state, these incentives could push people to make a worse choice and end up with less money.

Alternatively, if a household has a shorter time horizon--say, starting to save for college when the prospective student is 8 years old--then it may be advantageous to invest in a lower-quality, in-state 529 plan while reaping the immediate benefits of deductions and tax credits.

The Bottom Line on 529s

The proliferation of state-run plans and tax incentives has made things more complicated for people saving for college, and the tax nudges might not even be helpful for maximizing a student's college savings. It would be helpful if policymakers cut down the bamboo grove, leaving a clear path for college savers. Barring that, there are some powerful ways the tax code can help people save for college, but it’s easy to get lost.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)