Morningstar's Analysis of China Trade Scenarios

Are China and the U.S. headed for a new cold war?

The threat of a trade war with the United States roiled China’s equity markets in 2018, with about a 30% peak-to-trough decline in the Shanghai Composite. Earlier in 2019, optimism about a deal between the countries led Chinese equities to recover almost all of their losses, but the most recent tensions have diminished those gains. Deal or no deal, we think it’s no time to get complacent about the long-term threat of conflict between the U.S. and China and the economic impact this could have on the latter.

We’ve lowered our long-term (10-year average) China GDP growth forecast to 3.25% from 3.5% after incorporating the likelihood of scenarios of conflict between China and the U.S. In particular, we are concerned about the onset of a new cold war between the U.S. and China, a new era of great power conflict falling short of all-out war but in which the U.S. seeks to use all available economic means to curb China’s continued rise, the most important of which is cutting off almost all its trade with China. A new cold war is not our base-case scenario, but we assess its probability at 16%. In this scenario, China’s GDP growth takes a 1-percentage-point annual hit owing chiefly to lower trade, given the link between trade and economic growth.

Most analysis of the conflict has focused myopically on day-to-day developments. Instead, we take the long view. We use 200 years of data on trade and 500 years of data on great power conflicts to inform our probability estimates for our key scenarios. The key lesson of history is the strong propensity with which rising and ruling powers (like China and the U.S.) engage in conflict.

In this article, we discuss the key takeaways from our analysis, the main issues that are causing tension between the U.S. and China, and our trade scenarios.

Key Takeaways

- Academic research shows that trade is a key driver of economic outcomes across countries, and in China we think this is especially the case owing to its uniquely trade-focused development model. Therefore, we model that each 1 percentage point (of GDP) reduction in China's gross trade will reduce the country's long-term income level by 0.75%-1%.

- 500 years of history indicates that conflict is the norm when a rising power meets a ruling power, as documented by Graham Allison's Thucydides' Trap Project. In 75% of such cases, the outcome was war (not including the historical Cold War). Such a meeting is occurring today, as China's GDP already surpassed that of the U.S. in 2014 in purchasing power parity terms.

- The long-term history of U.S. trade policy history reveals that the U.S. hasn't always been a champion of free trade. From 1860 to 1913, the U.S. was among the most protectionist countries in the world. Crucially, the U.S. has exhibited substantial inertia in its trade policy, which means that President Donald Trump's actions today have much longer staying power than most others credit.

- Today, U.S. public opinion is hardly resoundingly in support of free trade (with 56% of Americans calling free trade "a good thing" in April 2018). Free trade is becoming a more partisan issue.

- The strong current U.S.-China trading relationship doesn't preclude conflict; the United Kingdom and Germany had as large bilateral trade shares of GDP on the eve of World War I as the U.S. and China do today.

- The key issues in focus today (such as intellectual property, cyberwarfare, or Taiwan) aren't new and will be in contention for years to come. Compared with historical great power conflicts, we think the U.S. and China have only about average odds at resolving the key issues of dispute.

- Although many would protest that U.S. military dominance means China can't risk war, we disagree. War with the U.S. is no longer unfathomable for China, thanks to its vigorous military upgrading. Rand research indicates that China has reached parity with the U.S. in several areas.

- Consumption-leveraged stocks will see the most impact, as we think most of the economic impact will fall on consumption expenditure, which we now expect to grow at about a 5.4% real rate versus our prior expectation of 6%.

The issues we elaborate upon below are both present in the current dispute between the U.S. and China and likely to remain relevant for years (if not decades) to come.

Intellectual Property Issues in China Complaints by the U.S. (and other nations) regarding China's intellectual property policies come in three general categories:

(1) China’s enforcement of legal protection of intellectual property (including patents, trademarks, and trade secrets) is insufficient.

(2) China’s government is actively aiding intellectual property theft, especially via cyberespionage.

(3) China’s government is “forcing” foreign firms operating in China to share intellectual property.

Broadly, intellectual property concerns with China stretch back to at least the late 1990s, as a key argument for accepting China as a member of the World Trade Organization in December 2001 was improving China’s intellectual property protection. China’s accession required (like all WTO members) that it join the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, which mandates minimum standards and enforcement mechanisms for intellectual property protection. Leading up to WTO accession, China passed a number of laws to fulfill (at least formally) these requirements. However, it doesn’t seem that the WTO has proved an effective mechanism for addressing the issues with China, as 90% of WTO cases during 2009-15 involving the four major economies (the U.S., China, Japan, and the European Union) were against China.

Within the category of IP protection (Item 1 above), recent U.S. complaints have focused on insufficient criminal penalties and lack of civil law enforcement. However, perhaps because China’s laws and enforcement in traditional areas of IP protection have arguably improved in recent years and reached more acceptable levels, broad criticism of China’s IP protection hasn’t been the U.S.’ key focus.

Instead, the focus has shifted to the second main category of IP issues: the active aiding of IP theft by Chinese government or state-sponsored entities, particularly via cyberespionage.

The cyberespionage issue has been building in recent years. In 2011, the U.S. Office of the National Counterintelligence Executive indicated that it sees China as the “most active and persistent perpetrators of economic espionage.” In response, in 2015 the U.S. (under President Barack Obama) and China reached an agreement whereby neither country’s government “will conduct cyber-enabled theft of intellectual property.”

Initially, the 2015 agreement seemed to work. According to one U.S. cybersecurity firm, network infiltrations by China-based groups dropped from over 60 per month in 2013 to only about 5 per month by mid-2016. However, the report acknowledged that it may be that Chinese attacks were getting harder to detect, rather than actually falling in frequency.

We’ve recently seen a substantial uptick in U.S. punitive measures on cyberespionage. In December 2018, the U.S. arrested two Chinese nationals with ties to the Ministry of State Security and charged them with conspiracy to hack into computer systems, wire fraud, and identify theft, over attacks at the Navy, NASA, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. At the same time, the U.S. government also implicated the Chinese in a hack of data on 500 million guests of the Marriott hotel chain. In October 2018, a third Chinese individual with ties to the Ministry of State Security was extradited from Belgium to the U.S. to face charges for stealing trade secrets from U.S. companies, including General Electric. Finally, Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou was arrested in Canada in December 2018 for extradition to the U.S. to face criminal charges over stealing trade secrets, obstructing a criminal investigation, and evading economic sanctions on Iran.

Recent U.S. statements have focused on the third category of IP complaints: forced transfer of IP from U.S. companies operating in China. This argument has a few components. First, in many industries, foreign companies wishing to operate in China can only do so via joint ventures with domestic Chinese companies. Additionally, Chinese regulatory authorities possessing the right to approve foreign investment often block foreign transactions that aren’t sufficiently conducive to technology transfer. Together, these measures put Chinese domestic companies in position to capture IP from U.S. partners.

On the one hand, the economic logic of this argument is muddled. It doesn’t explain why U.S. companies would repeatedly engage in transactions that are value-destructive, which would be the case if the value of lost IP exceeded the profits gained from operating in China. Effectively, the USTR is saying that private U.S. companies can’t be trusted to make decisions in their own economic interest. China economic expert Nicholas Lardy has argued that if forced technology transfer were such an issue, the U.S. should be able to organize a group of firms to bring a case to the WTO--something it has not done.

Still, it is the case that China agreed upon WTO accession to do away with these kinds of practices. Moreover, irrespective of the economic logic, this is an important issue to the U.S. administration.

What Does IP Theft Cost the U.S.? The Council of Economic Advisers estimated that cyberactivity cost the U.S. economy between $57 billion and $109 billion in 2016. The vast majority of the losses were assigned to China. This estimate was derived by estimating the impact on an affected firm's stock price following its announcement of a cyberattack. The report reviewed 290 cyberevents affecting 186 companies. Firms on average lost 0.8% of their stock price in the seven trading days following a cyberevent, resulting in loss on average of $498 million.

The IP Commission published a separate estimate indicating that the theft of intellectual property cost the U.S. between $180 billion and $540 billion annually (between 1% and 3% of GDP), with the vast majority of the activity assigned to China. This study was based on a 2014 methodology outlined by the Center for Responsible Enterprise and Trade and PricewaterhouseCoopers. The study used several proxies to estimate the costs, including research and development spending as a percentage of GDP, U.S. tax evasion costs, copyright infringement, illicit financial flows, and black-market activity.

The U.S. Trade Representative in 2018 estimated an economic impact of at least $50 billion.

A McAfee and Center for Strategic and International Studies report estimated in early 2018 that Chinese intellectual property theft cost about $15 billion annually and $115 billion when including recovery costs, financial crime, and security spending. It also assumed the 2015 agreement between former President Obama and President Xi Jinping over “no commercial espionage” remained intact. Assuming the 2015 agreement no longer holds, estimated Chinese IP theft would be around $25 billion-$30 billion annually directly. The report’s estimates were derived using costs of crimes where the quality of reporting was reliable, including maritime piracy and pilferage rates (0.5% and 2% of national income, respectively), and the cost of transnational crime. Transnational crime estimates have been reported by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the World Economic Forum, and Global Financial Integrity at 1.2%-1.5% of global GDP.

Can Made in China 2025 Be Reformed? Made in China 2025--China's official industrial policy--is also a source of U.S.-China tensions. The initiative (inspired to a degree by Germany's Industry 4.0) seeks to move China up the value chain across the economy. It focuses on 10 key industries, notably robotics, artificial intelligence, aerospace engineering, and electric cars. Beijing plans to achieve its goals through a combination of explicit target setting, direct subsidies, foreign investment, and forced technology transfer.

More crucially, the plan expressly promotes greater self-sufficiency across key technologies, aiming for 40% self-sufficiency by 2020 and 70% self-sufficiency by 2025, effectively reducing China’s dependence on foreign technologies while promoting domestic players.

However, these highly specific targets combined with government subsidies appear to violate WTO rules by requiring recipients to use domestic goods instead of international goods, thus distorting trade. Applying this set of WTO rules in China is complicated, as WTO rules are generally geared toward explicit state subsidies, whereas China tends to rely on off-budget support such as low-interest loans from its state-owned banking sector.

Therefore, Made in China 2025 has received considerable criticism from the U.S. and others, which wish to compete in these industries with China on fairer terms. China has responded to this pushback with minimal concessions, including officially abandoning the “Made in China 2025” name, although use of the name is still nearly ubiquitous in outside commentary.

We see no issues with a country enacting policies to improve its competitiveness, especially given that China’s average per capita income is still well below that of many developed countries. Other countries have used subsidies and tariffs to support nascent industries, and in a case like South Korea, it resulted in rapid economic growth. From China’s perspective, the country is being unfairly singled out in its pursuit of these policies. The issue is that its self-sufficiency efforts aim to displace many of the existing leading economies (Germany, South Korea, Japan, and so on) with large exporting high-tech centers without offering them comparable market and investment access in China.

China’s economy is still firmly in middle-income territory, with a per capita gross national income of about $8,700, below the middle-income ceiling of about $12,500, according to the World Bank’s 2017 assessment. Given the need for China to escape the “middle-income trap,” we think it is appropriate for the country to pursue initiatives like these to improve its competitiveness.

The range of outcomes that could be satisfactory to both the U.S. and China, in our view, extends from a more cosmetic changing of the name to something less aggressive to opening up the Chinese market to more international firms, reducing the level of protectionism available for the domestic entities. We believe the latter option is a particularly promising avenue of compromise, because reducing the level of domestic protections for the Chinese firms will force them to become more competitive faster, while still being encouraged to achieve the leadership goals set across the major industries.

U.S. and Chinese Goals for Taiwan Are Incompatible The U.S. and China have been locked in opposition over Taiwan's status since the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, when Chiang Kai-shek's U.S.-backed nationalist group moved to Taiwan to form the Republic of China while Mao Zedong's communist People's Republic of China established full control over the mainland. Since then, the status quo of de facto Taiwanese autonomy has persevered due to the tacit acceptance of both sides (although not without some Chinese testing of U.S. commitment, such as the 1955 Taiwan Strait Crisis).

Despite decades of stasis, unification remains important to China’s leaders (and plausibly to public opinion as well). The One China principle states that there is only one China in the world, Taiwan is part of China, and the government of the PRC represents the whole of China. President Xi has outlined the “Chinese dream” of unification with Taiwan under a “one country, two systems” model, which allows for a level of input and independence by Taiwan, but Taiwanese public opinion and leadership have rejected this approach thus far. Arguably, Taiwanese confidence can’t be bolstered by this model’s implementation in recent years in Hong Kong, where the Chinese central government has steadily increased its influence.

More recently, China has increased pressure on Taiwan through a variety of approaches. It has caused multiple other countries to break diplomatic ties with Taiwan, stepped up military deployments near Taiwan, and blocked Taiwan from participating in certain international events. The increased pressure now raises questions for the U.S. on how it should support Taiwan while maintaining relations with China. To complicate matters, China has stated that it will pursue military means if Taiwanese forces seek independence. In turn, the U.S. has supplied more than three fourths of Taiwan’s weapons since 1979, and its overall strategic security is supported by the U.S.’ commitment to the island’s security under the Taiwan Relations Act. In 2017, U.S.-Taiwan goods and services trade totaled $86.2 billion.

South China Sea Is a Setting for Potential Armed Conflict The South China Sea is an area of growing China-U.S. tensions due to its strategic importance for the U.S. and its allies/partners in the region (such as Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Singapore, Vietnam, and Indonesia). It is a major shipping channel with an estimated $3 trillion-plus in trade passing through it annually, large fisheries, and potentially sizable oil reserves. Because of its central location (including its proximity to mainland China), it is the most likely initial battleground in a potential hot war between the U.S. and China.

Territorial ownership of the South China Sea is very much in dispute, with both Taiwan and China claiming ownership of the entire region while Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, and others lay claim to portions. For the U.S., the key issue is that China has bucked international rules with its behavior in the region. For example, China has taken a narrow interpretation of the freedom of navigation international laws to exclude military vessels, whereas the U.S. and most international observers view freedom of navigation to include military assets under international law. Additionally, China ignored a 2016 UN tribunal’s decision against its claims over several islands in the South China Sea.

China has engaged in a significant island-building campaign since 2013, adding over 3,200 acres and military assets such as anti-ship missiles and surface-to-air missiles to the new land. The U.S. via Adm. Philip S. Davidson, head of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, has acknowledged that China is now capable of controlling the South China Sea in all scenarios short of war with the U.S.

Drug Deaths Could More Than Triple by 2027 China is a major exporter of fentanyl. Direct statistics on the amount of fentanyl being exported from China are not available, but U.S. and European authorities have said they believe a significant amount of the drug come from China. The U.S. wants China to crack down on production, primarily via regulatory means, and enforce the new laws strictly. In turn, China has introduced restrictions on more than 150 chemicals, but new chemicals are then introduced to make their way around the restrictions. In early April, China announced that it would ban all variants of fentanyl by declaring them controlled substances, which is a positive step. Still, the precursor chemicals used to make fentanyl are not banned, allowing them to be sent to Mexico, where fentanyl can be made to be exported to the U.S.

If the issue cannot be contained, some estimates place U.S. deaths at more than triple current levels by 2027, substantially deepening the crisis. The economic impact of the drug crisis on the U.S. is substantial. The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that 29,406 individuals died in 2017 from synthetic opioid overdoses, a category that is dominated by fentanyl. The number of deaths has increased significantly since 2013, when it was below 5,000. Using government estimates for the value of a human life, we see values from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency of $7.4 million and from the Department of Transportation (2015) of $9.4 million. Another academic study by Viscusi and Aldy puts the value of a human life at $7 million in 2002. If we use an estimate of $8 million per human life, the negative impact of the fentanyl crisis associated with China is currently $235 billion.

Both Sides Have a Strong Interest in a Stable North Korea North Korea is a highly important long-term issue for both the U.S. and China. It also has been a subject of discussion between the countries over the past year concurrent with the trade negotiations. The U.S. hosted a bilateral summit meeting with North Korea in Singapore in June 2018 to discuss the attainment of more peaceful relations, including the future denuclearization of the Korean peninsula. Since then, however, material progress has been minimal, possibly because China is encouraging North Korean defiance as a way of making the country a bargaining chip in trade negotiations with the U.S.

In the long run, we think China and the U.S. have an overwhelmingly strong shared interest in a stable (and, if possible, denuclearized) North Korea. For one, both countries have an obvious interest in mitigating any destructive risk to key trading partners in the region like South Korea or Japan. Beyond merely maintaining the ceasefire, we think both countries actually have an interest in creating a more transformative settlement. Although traditionally a pugnacious North Korea served as a useful buffer for China against the U.S. troop presence in South Korea, we think this use has outlived its purpose. China now seeks to enhance its influence and prestige in East Asia, and the perception that it is supporting a reckless and dangerous client state (and one that is the primary justification for the large protective U.S. troop presence in South Korea) is perhaps the biggest inhibitor to that goal. For the U.S., enhancing the safety of key allies is an intrinsic good.

Our Key Scenarios

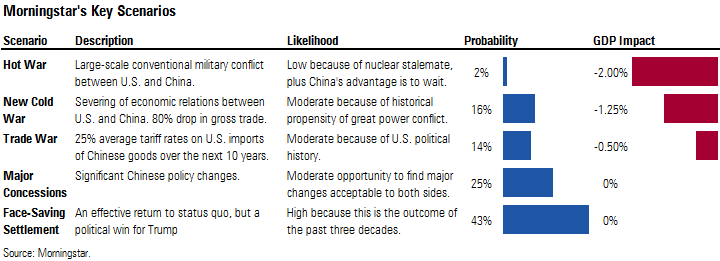

Hot War Large-scale military conflict between the U.S. and China. Military expenditures/GDP for both countries rise to historical wartime levels (around 15% for the U.S. during the Korean War and around 35% during WWII).

New Cold War Severing of most economic relations between the U.S. and China. Gross trade (combined exports plus imports) and foreign direct investment between the U.S. and China falls below 20% of current levels within the next five years and persists at that level. This would be a state of extreme geopolitical tension yet falling short of active military fighting (although minor military skirmishes and heavy cyberwarfare wouldn't be out of the question). In contrast to the trade war scenario, where economic means are used on behalf of economic ends, in the new cold war scenario, economic means are used primarily for geopolitical ends.

Trade War 15%-35% (expected value: 25%) average tariff rates on U.S. imports of Chinese goods over the next 10 years. This is already close to the default near-term outcome if the countries are unable to reach settlement: The average tariff rate is already set to hit 17% by perhaps late 2019, failing an agreement.

Major Concessions Significant Chinese policy changes, such as a 50%-75% decrease in bilateral trade surplus with the U.S., a large loosening of investment restrictions, or a strengthening of foreign IP protection to developed country levels.

Face-Saving Settlement Economically largely a return to status quo, but politically a win for the Trump administration and likewise acceptable to the Chinese.

The scenario with the largest (probability-weighted) impact is the new cold war. We think this scenario is about 16% likely, driven chiefly by the historical evidence of the propensity for great power conflict. In this scenario, we think China’s GDP growth falls by 100 basis points, to 2.5% on average over the next 10 years, due chiefly to a 21% drop in China’s exports.

Our trade war scenario has a 14% probability and a 40-basis-point impact on China’s 10-year GDP growth due to a 9% drop in China’s exports. This is a manageable impact for China, although we caution that the short-term impact could be worse due to the time needed to redeploy unemployed workers and capacity out of trade-affected industries. The real danger of the trade war scenario is that it boosts the conditional probability of a new cold war from 15% to 30%.

In our two key scenarios (new cold war and trade war), we focus on trade as a driver of economic impact on China. This is because trade is a primary grievance for the U.S., and trade would be the U.S.’ most powerful weapon against China in the new cold war scenario.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/010b102c-b598-40b8-9642-c4f9552b403a.jpg)

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/efa3b691-314a-4c23-8933-a09951d6793b.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T5MECJUE65CADONYJ7GARN2A3E.jpeg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_ffc6e675543a4913a5312be02f5c571a_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/010b102c-b598-40b8-9642-c4f9552b403a.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/efa3b691-314a-4c23-8933-a09951d6793b.jpg)