The Paradox of Skill Isn't Stock-Fund Managers' Only Problem

Converging style effects also hamper their chances at standing out.

Trouble With the Curve Michael Mauboussin of BlueMountain Capital Management released a paper about bond management, "Looking for Easy Games in Bonds." Tuesday's column will discuss Mauboussin's fixed-income claims. Today's article, however, addresses the single chart that Mauboussin devotes to stock funds, which demonstrates that active U.S. equity-fund managers have been torpedoed by the paradox of skill.

Here's an analogy. (Mauboussin's, not mine, although he did not invent the argument.) Baseball no longer has .400 hitters not because today's players are worse than their predecessors, but, paradoxically, because they are better. A stronger, deeper group of aspiring big-leaguers has made The Show more competitive. The gap between the leagues' best and worst players has shrunk.

The same process, most experienced observers believe, has occurred with U.S. equity-fund managers. They so rarely best the indexes, by a significant margin over a meaningfully long period, because they are collectively so skilled. All that ability clashing over the same few thousand securities, armed with similar databases and using similar techniques, is likely to lead to a Mexican Standoff.

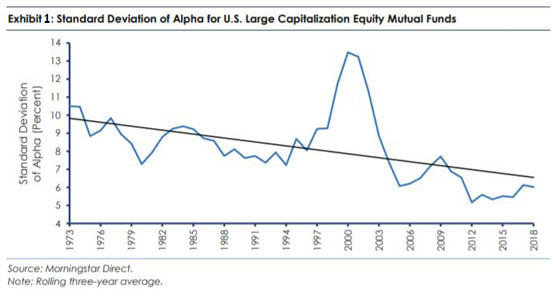

Mauboussin gives the picture. He computes the trailing three-year alpha for all U.S. large-company mutual funds (using a "single factor" as the benchmark--presumably the S&P 500), then calculates the standard deviation of those alphas. If the baseball analogy holds, that standard deviation should have declined over the years, because the gap between the best managers (that is, the ones who record the highest alphas) and worst managers (lowest alphas) has shrunk.

Heading Down Bingo! The chart below comes from Mauboussin's report. The source is listed as Morningstar Direct, because that provided the data, but the work is entirely BlueMountain's.

- Source: BlueMountain Capital

That looks convincing. What's more--to foreshadow Tuesday's column--the stock managers' chart doesn't resemble that of the bond managers. That bond managers haven't suffered comparable erosion presents some logical challenges (again, I will discuss that on Tuesday), but it does signify that alpha slippage isn't inevitable. Something these days is different for U.S. equity mutual funds.

One of which, surely, is Mauboussin's point: the professionalization of investment management. In 2019, Beating the Street, as Peter Lynch put it, takes more than deciding that a new franchise has an appealing pitch, or finding a profitable company that sells for less than the value of its current assets minus liabilities. (Good luck locating one of those.) The easy opportunities are long gone. That cannot be disputed.

At the same time, there's more to be said on the matter. The mutual fund boom, after all, is not the only major change to occur within the financial markets over the past half-century. Other factors may help to explain the shape of Mauboussin's charts--in particular, the behavior of investment "styles."

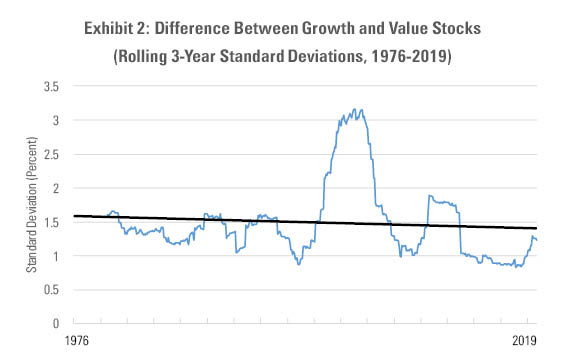

Growth Versus Value By Morningstar's count, about 60% of current large-company U.S. stock funds follow either growth or value strategies. Consequently, assessments of those funds' relative performances--including Mauboussin's alpha computations--are affected by the size of the performance difference between growth and value stocks. The greater the divergence, the greater the alpha dispersion.

This style effect caused a huge spike in Mauboussin's chart. Growth stocks dramatically outgained value-style companies during the late 1990s, only to trail by an even larger margin on the way down. As a result, manager alphas, when measured by a single market factor, ballooned. That apparent change was but an accident of time. It says nothing about portfolio managers' abilities.

(Mauboussin, of course, understands this outcome well, positioning the spike as being a temporary outlier that does not alter the overall conclusion. "There is a steady decline in standard deviation, save for a brief but explosive explosion during the dot-com bubble.")

I wondered whether there might be more to the growth/value affair than that inescapable New Millennium bulge. To that effect, I found the earliest possible index results for growth and value stocks (dating from the mid-1970s, from MSCI), calculated the absolute monthly return of the total-return difference between those two indexes, and then generated the trailing 36-month standard deviation of those differences. The output is analogous to Mauboussin's, only it measures a stock-market effect, as opposed to individual fund results.

- Source: Morningstar Direct

It's not a match, by any means, but it's suggestive. For both graphs, the first two decades are slightly down; the New Millennium brings a meteoric rise and fall; there is a smaller uptick around the time of the Financial Crisis; and then the decline resumes. In each instance, the overall trend line is down, albeit more steeply in Mauboussin's chart.

One can, I think, safely conclude that the convergence of stock-fund manager alphas is related to--although not perfectly correlated with--the convergence in performance of growth and value stocks.

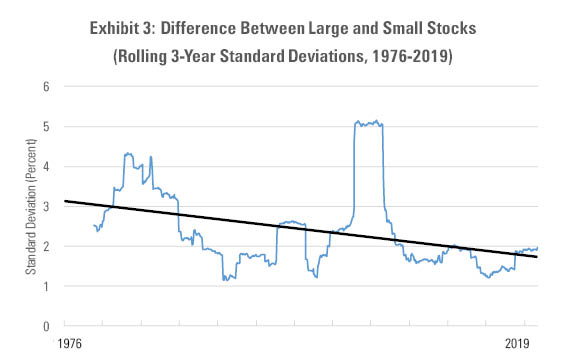

Large Versus Small After assembling those numbers, I decided to test for size. Large-company stock returns do not necessarily mirror small-company results; and large-company equity funds differ substantially in their exposures to secondary issues. Some have none, while others dabble considerably in small companies.

- Source: Morningstar Direct

The large/small effect is substantial; it's bigger even than the growth/value effect. In several key aspects (including the slope of its trend line) it echoes Mauboussin's chart so closely that one is tempted to state that it fully explains his findings. But that conclusion would be false. Although large-company funds do hold varying small-company weightings, those differences are moderate. If they were not, Morningstar would no longer classify the outliers as being large-company funds.

Wrapping Up In summary:

- Single-factor alphas for U.S. stock funds have gradually, if unevenly, declined over the past half-century.

- The performance differences between a) growth and value stocks and b) large and small companies have behaved similarly.

- Thus, some of the observed "paradox of skill" can be explained by structural changes in the stock market.

- The .400 hitters of the 1970s might really have been .350 hitters, operating under conditions (converging style effects) that made them look better.

- The .250 hitters of today might really be .300 hitters, operating under conditions (converging style effects) that make them look worse.

If it weren't for bad luck, stock-fund managers would have no luck at all.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)