Target-Date Funds: The Grades Are In

How have target-date funds fared since their 2008 failure?

Hard Times In early 2009, target-date funds were savaged. Not only did headlines proclaim their 2008 failure, but the Senate Special Committee on Aging held a hearing to evaluate whether target-date funds should be more strictly regulated. It is one thing for the SEC to investigate mutual fund categories, but quite another for Congress to do so.

(For those not entirely familiar with target-date funds, Tuesday's article from Karen Wallace covers the basics.)

The verdict on target dates may now be issued. It has been a full decade since the financial crash, which is quite long enough for judgment. This column grades the subsequent results of target-date funds, from January 2009 through December 2018, according to three performance measures:

1) Absolute

2) Against other funds

3) Against indexes

There are several varieties of target-date funds, sorted by time horizon. For this article, I evaluated the 2020 group, because that category carried asset allocations that most closely resembled those of traditional balanced funds. The typical 2020 fund started 2009 with 64% in equities and finished 2018 with 50%, as opposed to balanced funds' nominal 60/40 portfolios.

Absolute Performance: A On average, 2020 funds gained an annualized 8.1% for the decade, which equates to 6.5% after inflation. Roughly speaking, shareholder investments doubled. Such performance is why people buy equities. It is also why the mutual fund industry, supported by academic research and the Labor Department, gradually switched from automatically enrolling new 401(k) participants in cash to placing them into target-date funds.

Admittedly, one would expect risky assets to thrive during a bull market. The achievement is not remarkable. (An argument that hasn't prevented many hedge funds from setting short-term interest rates as their hurdle rates, so that they receive bonuses merely for participating in stocks' rise.) That said, target-date funds have two fundamental goals: 1) stay ahead of inflation and 2) outgain cash. Since the financial crash, they have easily accomplished both.

The overriding question asked of target-date funds in 2009 was, "Will these funds continue to hurt their shareholders?" The answer, 10 years later, is "Quite the contrary. Target-date funds will help them to finance a much better retirement."

The grade for absolute performance is A.

Against Other Funds: C Although those owning 2020 target-date funds are no doubt pleased to have beaten cash, they would be less happy if they hear that their investments trailed similar fund types. There are rivals to target-date funds--not only traditional balanced funds, as previously mentioned, but also various funds that market themselves as "moderate risk," which also invest about 60% of their assets in stocks.

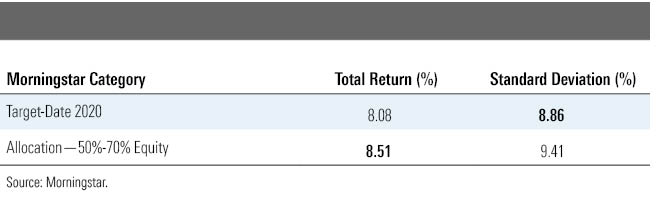

Morningstar places both the balanced and moderate-risk fund into a category that, prosaically, is called allocation--50% to 70% equity. (Not poetic, but every other name that we considered proved confusing.) Here are the 10-year annualized averages for the two categories. The best results are in bold.

Effectively a draw. The target-date funds made modestly less money than did the allocation funds but were also less volatile because they held slightly fewer stocks. The risk/return relationship for the two groups was virtually identical.

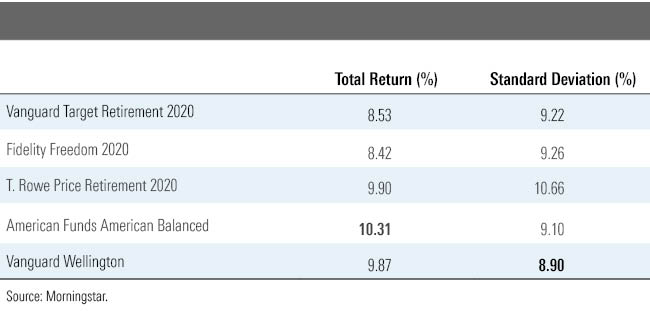

This comparison, while useful, overlooks an important point: Three providers--Vanguard, Fidelity, and T. Rowe Price--control 77% of target-date assets. Consequently, measuring the target-date fund "average" by equally weighting all providers, as was done in the chart above, doesn't necessarily indicate how the typical shareholder has fared.

As it turns out, those firms' target-date funds have each been above average. Even stronger, however, have been the two largest funds in the allocation--50% to 70% equity category, each of which was terrific.

Overall, target-date 2020 funds were competitive against allocation--50% to 70% equity funds, and the biggest target-date funds were better yet. When compared with a random allocation fund, the leading target-date funds fared well. But they could not keep up with the top allocation--50% to 70% equity funds.

The grade for performance against other funds is C.

Against Indexes: B Because target-date funds invest in strategies, as opposed to specified markets, they can't readily be benchmarked. We can compare a large-company U.S. stock fund to the Wilshire 5000, because the Wilshire 5000 contains that fund's investment universe, but we can't do the same for target-date funds. They can buy anything.

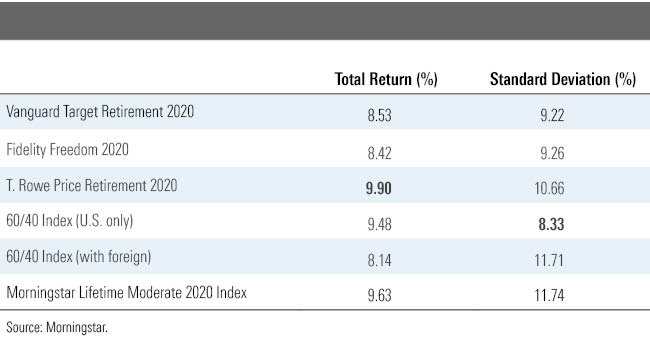

We can, however, suggest some reasonable alternatives. One is a simple 60/40 index, consisting of the Wilshire 5000 and the leading bond index, the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (which didn't become the standard because of the elegance of its title). Another is a 60/40 index that places one third of the stocks, that is, 20% of the portfolio, into foreign securities, via the MSCI ACWI ex USA index (a worse name yet). The final challenger is an index that Morningstar created to track target-date funds, the Morningstar Lifetime Moderate 2020 Index.

The 60/40 index that includes only U.S. stocks is something of an unfair comparison, since nearly all target-date funds own foreign equities, and since U.S. stocks showed so well for the decade. Consequently, that benchmark bested the Big Three 2020 funds, on a risk-adjusted basis. However, the three 2020 funds showed roughly as well as Morningstar's index, when risk-adjusted, and they were markedly superior to the 60/40 index that included foreign stocks.

The grade for performance against indexes is a B. Somewhat surprisingly, this task proved less difficult than competing against rival funds.

Finally, target-date funds have excellent investor returns--which Morningstar defines as the money that shareholders make from funds, as opposed to the paper gains from official total returns. That is because target-date investors are unusually loyal; they stay with their funds, rather than trade them. This benefit owes more to the nature of default 401(k) programs than it does to the features of target-date funds, but it nevertheless should be noted as a target-date virtue.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar’s investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)