Clean-Up: How Fee Bundling Kills Performance

Cheaper, "unbundled" funds succeed far more often than pricey, "bundled" offerings.

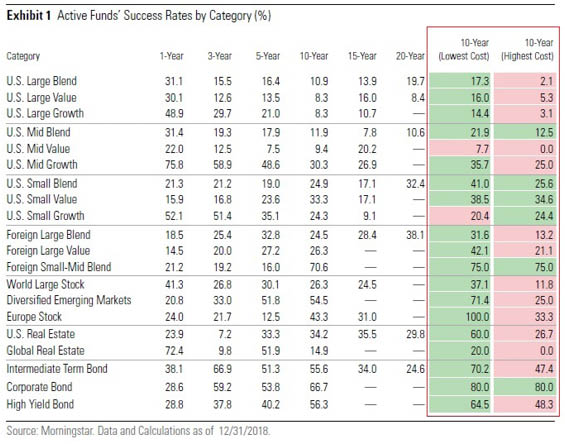

Last week we published the latest installment of the Morningstar Active/Passive Barometer. The Barometer is a useful report--it tallies up the number of active funds that have beaten their index-fund peers over various time horizons. Using the Barometer, investors can better gauge their odds of succeeding with active or index funds across the 20 Morningstar Categories it tracks.

Among other things, the most recent edition of the Barometer found that only 24% of active funds had beaten their average index-fund rival over the trailing 10 years ended Dec. 31, 2018. It also found that the cheapest active funds were about twice as likely to succeed than the priciest funds. Above all, the Barometer's findings buttress the argument that cost matters.

Why Do Pricey Funds Exist? That invites an obvious question: Why are there costly funds to begin with? If cheap funds are much likelier to succeed, then why wouldn't managers seek to minimize the expenses they levy? A cynic would say it's because managers are human and therefore given to charging whatever the market will bear. But the more-nuanced explanation is that it's structural: Many funds charge more because they wouldn't find an audience otherwise. That is, to sell they feel they must bundle distribution and advice fees into the fund's price tag, those fees going to intermediaries that ferry the funds to investors.

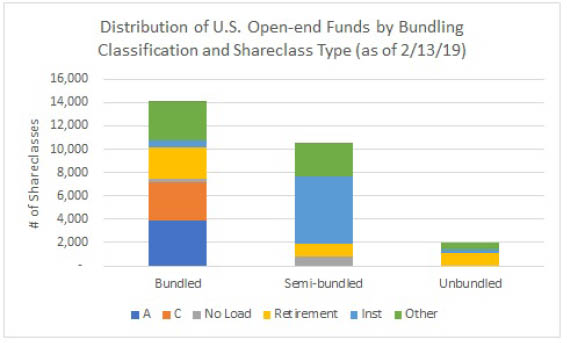

We recently launched a new taxonomy that classifies funds based on whether they bundle distribution and advice fees. Technically known as the "Clean Share--Service Fee Arrangement" data point, the three classifications are "bundled," "semi-bundled,"and "unbundled," as explained further below:

- Bundled: Funds that levy 12b-1 fees--that is, A and C share classes and certain retirement share classes.

- Semi-bundled: Funds that eschew 12b-1 fees, but "revenue-share" by paying a portion of management or other fees to platforms for shelf space or face time with advisors.

- Unbundled: Funds that charge only for investment management and fund operations; these funds don't levy 12b-1 fees and refrain from revenue-sharing.

The following table breaks down the number of fund share classes by bundling classification and share class type:

- Source: Morningstar Direct

We see that bundled and semi-bundled funds proliferate, accounting for 53% and 40% of all share classes, respectively. What's also striking is how poorly share class names describe whether a fund charges marketing and distribution fees or revenue-shares. For instance, only around 5% of share classes labeled as "institutional" qualify as unbundled. That might seem surprising, as institutional shares ordinarily enjoy the distinction of being a fund's cheapest and most bare-bones share class. In truth, the vast majority of these share classes levy 12b-1 fees or participate in revenue-sharing.

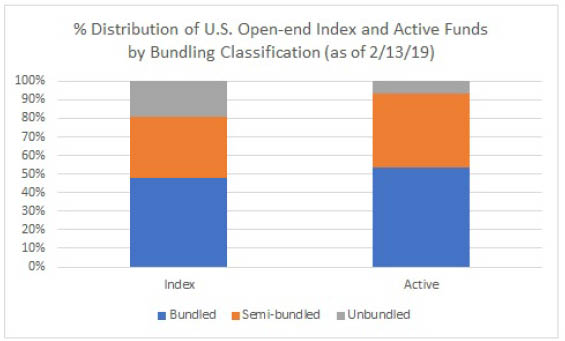

Another surprise: Many index mutual funds embed distribution or advice fees in their expense ratios or pay revenue-sharing out of their operating expenses. Indeed, the percentage breakdown of funds by bundling classification isn't too different between active and index open-end funds, as shown below.

- Source: Morningstar Direct

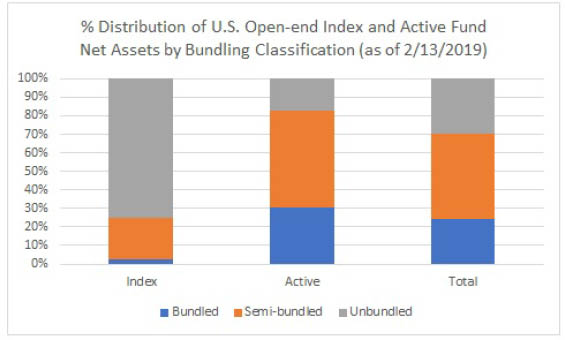

Interestingly, while unbundled share classes account for just 7% of all open-end index funds, they have come to soak-up a much bigger share of net assets.

- Source: Morningstar Direct

Indeed, unbundled share classes recently accounted for nearly a third of all U.S. open-end mutual fund assets, as investors have continued to flock to index funds and truly "clean" shares of active funds, such as institutional share classes of funds that forgo 12b-1 fees and revenue-sharing.

Using these new classifications, we can assess the success of active funds in a different way, based on whether they bundle fees or not.

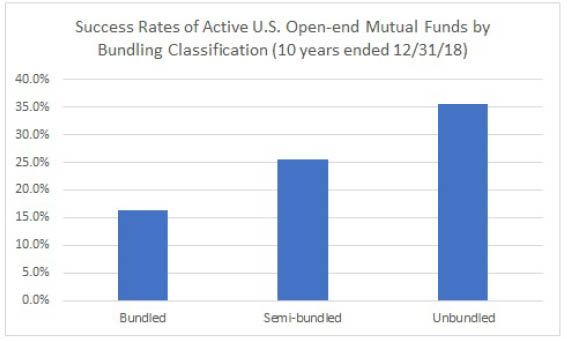

Success Rates: By Bundling Classification Building on the Barometer's approach, we broke active funds in the 20 Morningstar Categories down into bundled, semi-bundled, and unbundled cohorts. Then we counted up the number of funds in each cohort that beat the equal-weighted composite index-fund return for that category over the 10-year period ended Dec. 31, 2018, and divided by the total number of funds that began the period. When we aggregate those figures across the 20 categories, it yields the following success rates.

- Source: Morningstar Direct

To summarize the chart's findings, only around 16% of the active funds that bundled distribution and advice fees into their expense ratios beat the composite passive fund's returns, on average. A slightly higher percentage--about 25%--of semi-bundled funds beat the bogy. Highest of all was the success rate of unbundled funds, which at roughly 36% more than doubled that of bundled funds.

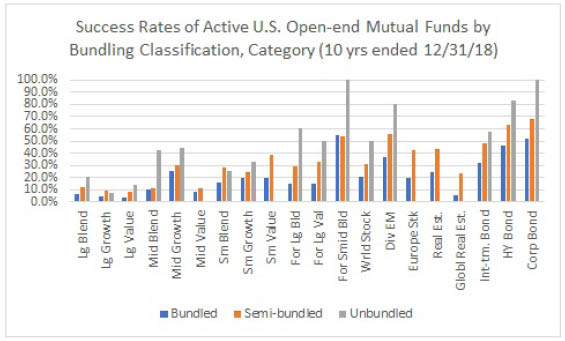

The chart below provides further detail on success rates by category over the 10-year period. Unbundled funds succeeded more often than bundled funds in 15 of the 18 categories that had at least one unbundled fund (in the two categories that didn't--Europe stock and global real estate--semi-bundled funds succeeded more often than bundled funds). The median success rate improvement from bundled to unbundled was a hefty 22% across the 18 categories.

- Source: Morningstar Direct

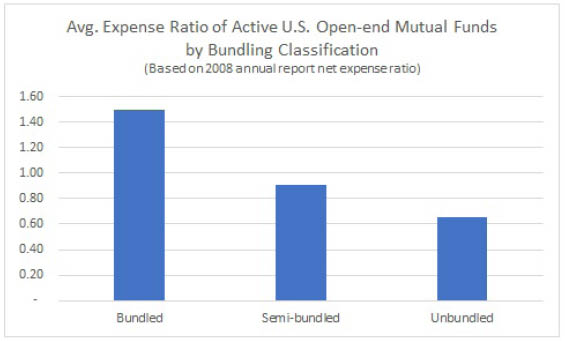

Why did unbundled funds succeed so much more often than bundled funds? Two reasons: They cost less, and they survived more often. To start with the obvious--cost--bundled funds levied meaningfully higher fees than semi-bundled and unbundled funds, on average.

- Source: Morningstar Direct

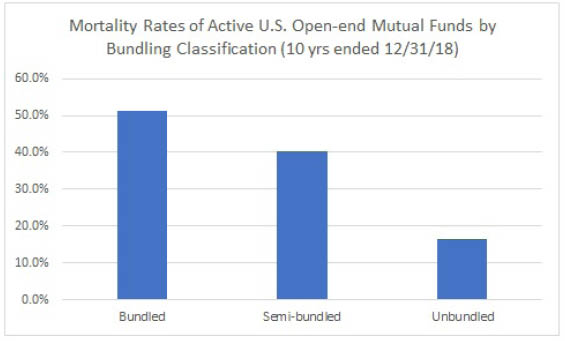

A fund can't very well succeed if it dies. That also partly explains the greater futility of bundled and semi-bundled share classes, which on average were merged and liquidated away at least twice as often as unbundled share classes over the decade ended December 2018.

- Source: Morningstar Direct

Taken together, unbundled share classes' lower costs and higher odds of survival largely explain their greater success in beating a relevant index-fund substitute.

Conclusion Our research has found that cheaper funds are likelier to succeed than pricey funds, a point reinforced by the findings of the recently published Morningstar Active/Passive Barometer report. What's less clear, though, is why fund managers don't take the hint and minimize fees to boost their odds of success and, in turn, drum-up greater demand from investors (who love a winner). A key reason is that to reach investors through intermediaries, managers feel compelled to embed distribution and advice fees into their funds' expense ratios. This practice of bundling fees keeps costs high and impedes success, which our analysis of success rates by bundling classification confirms. Indeed, bundled share classes succeeded less than half as often as unbundled share classes over the decade ended December 2018.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)