How Life Expectancy Affects Retirement Planning

Morningstar contributor Mark Miller looks at longevity assumptions used most in retirement plans. Are they realistic?

Retirement plans revolve around two critical numbers: your retirement date and how long you will live past that point. It's possible to forecast or even control your retirement date--sometimes. But--to state the obvious--any date you pick for your mortality is just a guess, for most of us anyway.[1]

Most financial advisers assume extreme longevity in their retirement plans as a way to "test" the odds of success against longevity risk. Clients often see illustrations assuming a lifespan of 95 or 100. And certainly, some of us will be fortunate enough to reach those lofty numbers.

"For a 65-year-old couple that has an adequate fear of running out of money, making a plan for age 95 or 100 is reasonable," says Wade Pfau, a professor of retirement income at The American College of Financial Services. "It makes sense to pick an age beyond your actual life expectancy, because you have a 50% chance of getting there."

But a plan using these conservative assumptions also creates risks and challenges.

Extreme longevity dates at least suggest the need to sock away much more money, and that can be intimidating--even paralyzing--for some, especially younger people who haven't yet saved much.

Another risk is oversaving and cramping consumption beyond what is necessary, or working longer than you need to.

"One of the risks is that you won't enjoy your retirement as much as you could," says Dirk Cotton, founder of JDC Planning.

Some researchers are beginning to explore ways to use biological markers to peg more realistic longevity assumptions. Moshe Milevsky, a professor of finance at the Schulich School of Business in Toronto, has been developing an approach to planning based on "biological age." It won't be long, he argues, before scientists can predict longevity within a couple years.

Currently, it is possible to get a reasonable guess on your likely longevity by using the Social Security Administration's longevity calculator, which is based on the mortality data it tracks, or by using this longevity illustrator created by the American Academy of Actuaries and the Society of Actuaries.

Cotton believes plugging in "100" as your lifespan makes sense--but only to illustrate what you're up against. He thinks there is only one valid way to deal with longevity uncertainty, as he points out in a recent blog post:

“I'm going to make a claim that may sound a bit outrageous: there is only one grand retirement-funding strategy. That strategy is to allocate some amount of retirement plan resources to generate a floor of safe lifetime income, to invest the remaining assets, if any, in a risky aspirational portfolio, and then to decide how to spend the risky assets throughout retirement. The correct balance will depend on how willing you are to risk losing your standard of living for the chance of having an even higher one.”

Steve Vernon takes a similar approach. A consulting research scholar at the Stanford Center on Longevity, he advocates covering basic living expenses by setting up a series of "retirement paychecks" that are guaranteed to last the rest of your life. Any remaining savings are the gravy--use them for discretionary expenses like travel and entertainment. Vernon lays out this approach in his excellent recent book, Retirement Game-Changers: Strategies for a Healthy, Financially Secure, and Fulfilling Long Life.

Vernon starts with a careful projection of likely expenses in retirement; then, he suggests matching up nondiscretionary spending--to the extent possible--with guaranteed income sources. Drawdowns from retirement savings are extras in his model.

How to fund the guaranteed income stream? Start by developing a plan to maximize Social Security income through delayed filing and spousal coordination.

"When you look at this, you see clearly the problem with making a claiming decision based on the old break-even approach," Cotton says. “If you live beyond that point you are better off--and if you live a lot more years, you are a whole lot better off."

Beyond Social Security, the choices come down to bonds or annuities. Cotton thinks annuities offer a better solution.

"You can buy more income for your money with an annuity than you can by building a bond ladder to age 85 or 100," he says. "With annuities, you get the benefit of mortality credits."

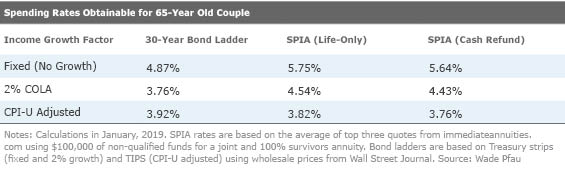

Pfau has looked at the bonds versus annuity question from the perspective of obtainable spending rates in retirement and draws the same conclusion in this table:

"It's clear that with annuities you can spend more, because if live longer you get a subsidy from the risk pool," he says.

Finally, Cotton advises adopting a dynamic, not static, approach to your retirement plan, adjusting as you go.

"It's like a sailing expedition," he says. "You start with a destination and a plan in mind, but if you get one-third of the way there and you're off course and two days behind, you really have to change plans. It's the same with retirement. The perception of retirees and advisors that you can make this plan once and be done is wrong. You need to do it periodically, almost every year."

[1] Mark Twain predicted his own date of death. He was born in 1835 shortly after a visit from Halley's Comet, and joked that the next time it came he would "go with it." He died one day after the comet's return in 1910.

Mark Miller is a journalist and author who writes about trends in retirement and aging. He is a columnist for Reuters and also contributes to WealthManagement.com and the AARP magazine. He publishes a weekly newsletter on news and trends in the field at Retirement Revised. The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)