The Active Stock Fund Slump Explained

Pre-fee returns are sliding, funds are performing more alike, and the 'wrong' styles are leading.

Active U.S. stock funds are succeeding less often than they used to. This likely reflects the impact of a few trends: 1) Funds are outperforming before fees less often and by smaller margins, on average; 2) Styles like size and value are performing more alike; and 3) The "wrong" styles (large-cap and growth) are leading.

Some of these trends should abate. For instance, the small-cap and value styles are likely to rebound. But others appear to be more structural; this argues for funds to reconsider their fees.

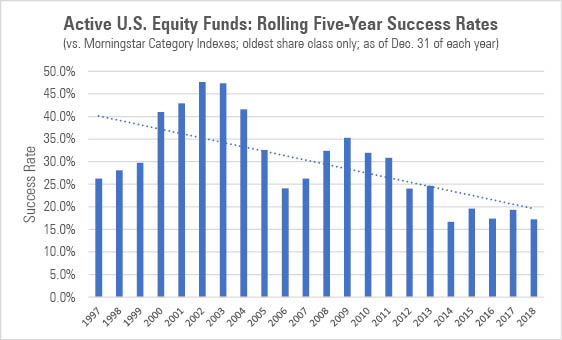

Tough Game, Getting Tougher Active management is tough; most active stock funds routinely fail to beat a relevant index over a market cycle. But it seems to be getting even harder--active U.S. equity funds have been succeeding less often recently than they used to.

To illustrate, the chart below shows the percentage of active U.S. stock funds that beat their benchmarks after fees over the five-year periods ended between December 1997 and December 2018. While the success rates jump around a bit from one rolling period to the next, the longer-term trend is lower.

Source: Morningstar.

The question is why. In this piece, we explore several factors that could explain why active U.S. stock funds are succeeding less often than before.

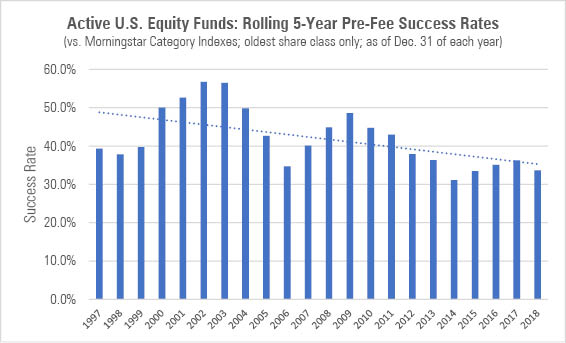

Shrinking Margins A fund's net excess returns, that is, the margin by which it beats or lags an index after fees, are a function of its pre-fee excess returns and its expenses. If a fund beats its index before fees by a larger margin than its annual expenses, then it will also beat the benchmark after fees. Given this, it makes sense to examine the trend in success rates based on pre-fee returns, which we do in the chart below.

Source: Morningstar.

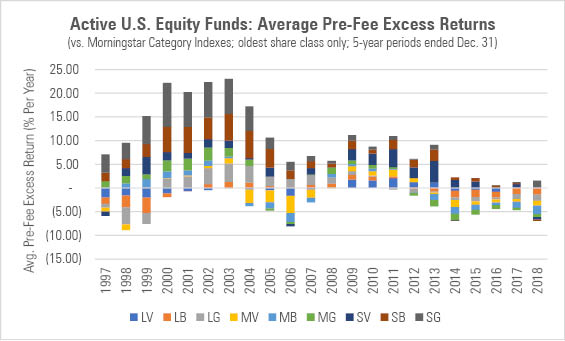

Pre-fee success rates have been gradually declining over time. And why? Average pre-fee excess returns have been grinding lower, as shown below.

Source: Morningstar.

Some argue this trend reflects the impact of greater competition, with marginal investors exiting the active-investing field, leaving behind a collectively more skilled and informed group of investors to scrap over every morsel of excess return.

While that's open to debate, one proxy for skill is the payoff of different investing styles. For instance, if investors are better informed about "tilting" to styles like size and value in order to capture excess returns, then it would be useful to examine the spread of returns between different investing styles. Are tilts continuing to pay, that is, is there meaningful separation in the returns of those styles?

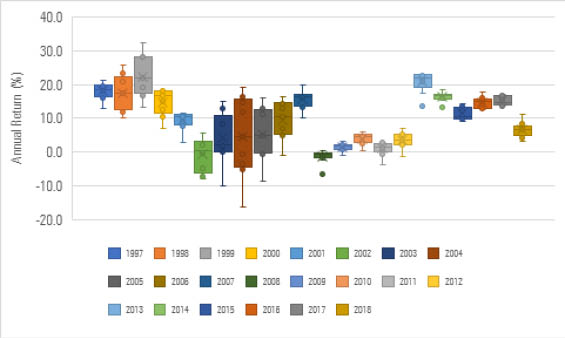

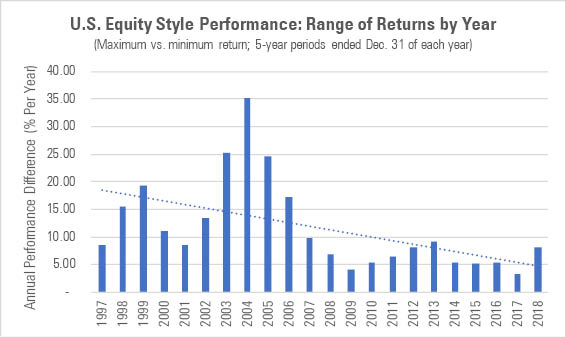

Clustered Returns The short answer is that style tilts ain't payin' like they used to: There's much less dispersion in the returns of the popular investing styles. To illustrate, the chart below plots the returns of the Morningstar Style Box indexes corresponding to the nine regions of the style box for the five-year periods ended Dec. 31, 1997, through Dec. 31, 2018.

Source: Morningstar. For the five-year periods ended Dec. 31, 1997, through Dec. 31, 2000, we used the relevant Russell style indexes; for all other five-year periods, we measured using the appropriate Morningstar Style Box indexes.

The gap between the best- and worst-performing investing styles has narrowed significantly in more-recent periods. We can see this trend even more clearly when we plot the range (maximum by minimum) of returns only, as shown below:

Source: Morningstar. For the five-year periods ended Dec. 31, 1997, through Dec. 31, 2000, we used the relevant Russell style indexes; for all other five-year periods, we measured using the appropriate Morningstar Style Box indexes.

While this isn't fatal to active stock managers who tilt into styles other than the one to which they're assigned--for instance, a large-cap manager dipping into small caps or a value manager dabbling in growthier names--it leaves them with much less margin for error.

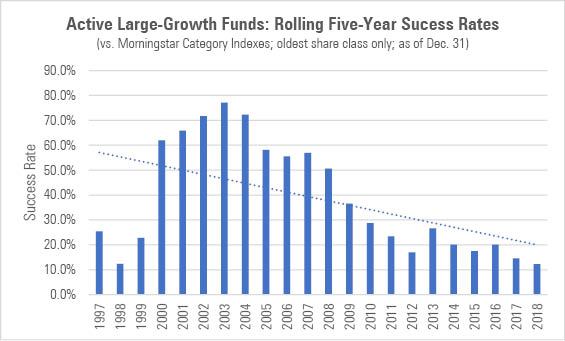

Wrong Kind of Leadership Unfortunately, the challenges go beyond dispersion of returns. Indeed, as far as many active stock fund managers are concerned, the wrong styles--think large-cap and growth--have been leading in recent years.

To understand this, consider that when managers tilt to styles other than the style to which they have been assigned, they're implicitly betting that their assigned style will slightly underperform these other styles (or that their stock-picking prowess will carry the day). Given this, it's most beneficial to them when their assigned style lags other styles, as the fund's index will be more exposed to that underperforming style because benchmarks tend to be more style pure. But when their assigned style leads other styles, then the benchmark is often tough to beat.

In recent five-year periods, the returns of large-company stocks have topped those of small-company stocks, while growth-oriented names have beaten cheaper fare, as shown below.

Source: Morningstar.

This is unwelcome news to large-cap and growth managers, as it means that their assigned styles have been leading and, conversely, that the other styles to which they've been tilting, like small and value, have been lagging. Perhaps not coincidentally, the slump has been deepest among active large-growth funds, where success rates have slipped below 15% in recent five-year rolling periods.

Source: Morningstar.

The Price Is (Often) Wrong The good news is that some of these trends--such as the large-cap and growth styles leading the pack--are cyclical and thus likely to abate over time. But it's at least possible that decaying pre-fee excess returns and lower dispersion of styles reflect structural changes that have taken place.

If this is the case, then fund companies will need to redouble their commitment to cutting fees. While some progress has been made, it doesn't appear to be enough, as average pre-fee excess returns have fallen at a faster rate than fees. Consequently, many funds find themselves in an untenable position where their annual expenses approach if not exceed the excess return they can reasonably be expected to generate before fees.

To adapt, funds will have to accelerate the process of cutting fees, both by eliminating nonmanagement fees (such as marketing and distribution, fund administration, transfer agency, and so on) and by taking a knife to management fees themselves.

Conclusion Active U.S. stock funds are succeeding less often than they used to. This is likely explained by the impact of a few factors, including the shrinking margin of outperformance before fees; styles like value and size performing more alike; and the "wrong" styles, such as large-cap and growth, leading. While it's reasonable to assume that some of these trends will abate and even reverse over time, some appear to be structural. Given this, fund companies will need to consider taking further steps to slash fees, as many funds appear to be priced to fail as is.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)