Stress-Testing Your Retirement Asset Allocations

The effects of changes in stock performance and time horizon.

Historically Strong Tuesday's column showcased stocks. It demonstrated that if equities continue to perform as they have since 1900, they could reasonably account for most of a retiree's initial asset allocation, assuming the retiree has a 30-year time horizon. Withdrawing money from an inconstant portfolio can be dangerous, but historically stocks have earned so much more than bonds/cash that their rewards have outweighed their drawbacks.

The source was a working paper by IESE Business School's Javier Estrada and Windham Capital Management's Mark Kritzman.[1] The duo developed a new measure for evaluating the viability of retirement asset allocations, called "the coverage ratio." The coverage ratio: 1) assumes ongoing withdrawals (4% annually, adjusted for inflation); 2) moderately rewards portfolios for creating legacy assets; and 3) steeply penalizes portfolios for shortfalls.

The paper also showed that if future stock performance was weaker than in the past, equities would quickly lose their appeal. This finding is obvious, but the paper puts specifics to the intuition, and it highlights the damage that greater volatility inflicts on withdrawal strategies. Boosting the standard deviation of simulated stock-market results lowers the recommended equity allocation as severely as does reducing the expected gains. For retirees, the risk that comes from portfolio gyrations is actual, not theoretical.

Time Effects Today's column considers the additional variable of time. It's one thing to hold a large stock position at age 65, planning for the next 30 years. It's quite another to do so two decades later, at age 85, when the portfolio is probably smaller. (As with most retirement-withdrawal researchers, the authors assume that investors will spend down capital, if required.) That may call for a very different allocation.

We'll evaluate three stock-market possibilities: 1) Bullish, wherein U.S. stocks (and again, many other developed markets) behave much as they have in the past; 2) Neutral, which assumes a lower equity-risk premium and modestly bumpier ride; and 3) Bearish, which halves the historic real stock-market return and which further boosts volatility. (Those are my labels, not the authors'--and their paper contains many more performance scenarios.)

When examining the effects of time horizon, Estrada and Kritzman adopted an open approach to modeling the problem. They could have begun the process by placing the newly minted retiree, possessing a 30-year time horizon, into the recommended asset allocation from their paper's previous exhibit. (That was the material covered in Tuesday's column.) Then, they could have checked how that allocation behaved along the way and modified it if necessary. Such a study would provide a two-step suggested allocation, with both sections being optimal, as measured by their coverage ratio.

Instead, the authors assumed no knowledge of the retiree's initial asset allocation. The investor might have placed 100% of the withdrawal portfolio into equities, or none at all, or (mostly likely) something in between. The authors therefore generated simulations across various asset allocations. For each simulation, they stopped at a given point in time, calculated how much money would have remained in the portfolio, and then determined the optimal average asset allocation going forward, as measured by the coverage ratio.

Whew! There is a simple way to envision the output, though. For each of the three stock-market possibilities, the results indicate how retirees in typical situations might alter their asset allocations over time. These aren't perfect retirees: Only one in 11 of them entered retirement with the "correct" allocation, as previously estimated by Estrada and Kritzman. They're just ordinary investors, trying to wring annual withdrawals of 4% from their portfolios while preserving their wealth as best they can.

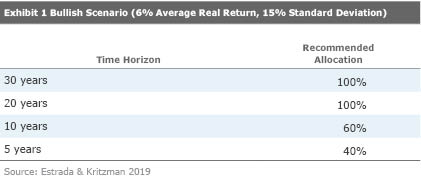

What Was First, the bullish totals. As previously stated, these come from using stock- and bond-market assumptions that closely resemble those from history. The average annual equity return is 6%, with 15% standard deviation. (All figures are presented in after-inflation terms.) Bonds are at 2% and 3%, respectively. The simulations create each year from scratch, so not only does the sequencing vary from one simulation to the next, but also the overall result.

(That is, the average annual equity return for each 30-year simulated period is not forced to be 6%. Each year is drawn from a normal distribution that is centered at 6%, but that doesn't mean the 30-year average will land that way, any more than flipping 30 coins will automatically lead to 15 heads and 15 tails.)

The upshot: If stocks and bonds act as they previously have, then a 100% equity portfolio makes mathematic sense even for 20-year time horizons--that is, for an investor who retired at age 65, is now 75, and continues to plan for withdrawals until age 95. Of course, mathematic sense as computed in a research study, when expected investment performance is specified, is different from facing real-world uncertainties. The answer sheds insights into the interplay between higher rates of return and greater volatility, for those following withdrawal strategies, but it is not necessarily real-life advice!

As the time horizon shortens, the optimal equity position declines, to 60% for those with a 10-year horizon (that is, the 85-year-old) and 40% for a five-year horizon. Again, this result assumes a wide variety of initial asset allocations--the allocations used from the date of retirement until that point. My suspicion is that those investors that held more-aggressive initial allocations would be permitted to own more stocks later during retirement, because they would have built a larger cushion. But that is only a suspicion.

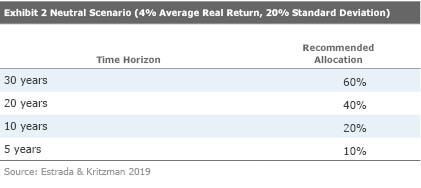

What Might Be Slicing 2 percentage points from stocks' annual returns and raising their annual standard deviation to 20% from 15% makes a big difference!

Exhibit 2 reinforces the ongoing point: Much of the basis for holding a majority-equity portfolio during retirement rests upon the relatively optimistic belief that the stock market's future will resemble its past. There are good arguments for why that might not be so. (One of which I will mention in my next column.) Even moderately worse equity results lead to sharply lower allocations in Estrada and Kritzman's paper.

The Bearish View

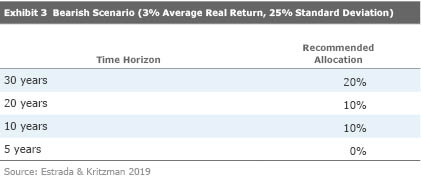

For the bearish scenario, stocks make only 1 percentage point per year more than bonds while possessing 5 times the volatility. Unsurprisingly, even their diversification benefits cannot save them. Should their relative performance be that poor, equities will offer little help to retirees.

[1] Estrada, J., & Kritzman, M. 2019. "Toward Determining the Optimal Investment Strategy for Retirement." J. Investing, submitted. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3303153

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MFL6LHZXFVFYFOAVQBMECBG6RM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HCVXKY35QNVZ4AHAWI2N4JWONA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EGA35LGTJFBVTDK3OCMQCHW7XQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)