Enduring Philosophy

At Aristotle, the emphasis is on long-term ownership.

In every issue, Undiscovered Manager profiles a noteworthy strategy that hasn’t yet been rated by Morningstar Research Services’ manager research group.

When Howard Gleicher and his colleagues cofounded Aristotle Capital Management in 2010, they brought extensive experience in the asset-management industry and a shared investment approach.

“Some of us were working together for 20 years or more. Some were from different firms, but practiced the same investment philosophy,” says Gleicher, CEO and chief investment officer. “We believe that a focus on long-term value creation by companies will over time result in optimal returns.”

It was a desire for autonomy that led them to join forces to form Aristotle. “Many of us had been part of organizations that either were or became part of much larger organizations,” says Gleicher, who came from Metropolitan West Capital Management, which was acquired by Wachovia, which was in turn acquired by Wells Fargo. “Those institutions don’t necessarily offer investment professionals the environment they thrive in. Talented people want to be independent. Being an employee-owned firm has enabled us to attract and retain additional people to our firm.”

Today, the employee-owned investment advisor manages more than $20 billion, the bulk of which is in the flagship large-cap value-oriented strategy run from its Los Angeles headquarters. (Affiliated offices run complementary equity and fixed-income strategies from Boston, New York, and Newport Beach, Calif.) The firm serves primarily institutional clients via separate accounts, but began offering the strategy as a mutual fund,

Employee ownership and the investment approach were the factors that drew Greg Padilla to join the growing firm in 2014. He came to Aristotle after serving on global strategies at Vinik Asset Management and Tradewinds Global Investors and was named comanager of the domestic value strategy in early 2018.

Padilla, who lives in the Los Angeles area with his wife and two young daughters, says, “Los Angeles is a close-knit investment community. I was familiar with the team and had seen their consistent success, and liked that employee incentives are aligned with clients.”

Gleicher and Padilla serve as both portfolio managers and analysts, alongside a dozen other members of the research team. All the analysts have “a tremendous amount of autonomy,” Padilla says. “We look for self-motivated, curious individuals who love studying businesses, as opposed to trading stocks. Everyone on the team either is or is on the path to becoming an owner of the firm, so all will benefit if we do well for our clients.”

High Hurdles The team seeks quality companies—those with sustainable advantages, helmed by experienced management teams—selling at an attractive valuation, with a catalyst likely to boost performance. These aren't deep-value picks; the strategy lands in the large-cap blend Morningstar Category. Padilla says that they do not screen out companies on the basis of criteria such as price; rather, as analysts come across ideas, they are added to an investment watchlist.

“It’s about understanding businesses, and why certain businesses around the world seem to flourish while others languish,” sums up Gleicher. “In most cases, the companies we invest in are not those charging the lowest prices. But they provide an optimal product that fits the right need at the right time at the right place.”

The hurdle is high for a stock to make it into the high-conviction, concentrated portfolio: The strategy generally holds 35 to 45 stocks, with annual portfolio turnover historically under 35%. In addition to monitoring existing holdings, each analyst has several companies at some level of due diligence.

A catalyst can be the differentiating factor between two strong competitors. Gleicher offers

He emphasizes that macroeconomic factors, such as rising rates, that are outside the control of an individual business are not sufficient catalysts. For example, while some companies and industries stand to benefit in the current rising-rate environment, that would not be enough to prompt an investment in one of these firms.

New positions are typically initiated at 2.5% stakes, and the team rarely trims or adds if the company keeps executing as expected. As a risk control, however, companies cannot exceed 6% of assets.

“We’d seen what he’d accomplished at Covidien, and that gave us confidence,” says Padilla. “He joined the firm, spun off Baxalta, optimized the portfolio, and began to invest in innovation. Everything we’d identified played out over a three-year period.” By the end of 2017, Baxter no longer met their valuation and catalyst criteria.

When making buy and sell decisions, sector exposure matters only at the margins. As a broad risk-control measure, the portfolio can have no more than twice and no less than half the major sector weights (such as financials, healthcare, etc.) of the S&P 500. Gleicher says that this limit has affected investment decisions only several times in the past 20 years.

Gleicher says that sector classification doesn’t limit a company’s prospects, using

Relative Risks In addition to the 6% ceiling on position size and the broad limits on sector exposure, the managers monitor the portfolio for risks such as interest-rate sensitivity and economic cyclicality. Cash, however, is not used as a risk buffer; the cash weighting generally remains below 5%.

“Sometimes companies can be classified in different industries but are subject to the same forces. Understanding companies is the greatest tool that we have to reduce risk levels in the portfolio,” Gleicher says. “If you truly understand what makes a company tick, you can watch those factors.”

Companies within the same industry can offset each other’s particular risks. For example,

“There are lots of other reasons why we’ve invested in these businesses,” Gleicher says, “but it gives us some comfort to know that while one of our holdings could be hurt by Humira going off patent, two others may benefit.”

Analysts cover sectors on a global basis; for example, the healthcare analyst who covers U.S.-domiciled AbbVie also covers Switzerland-based Novartis. That enables them to evaluate competition faced by U.S. firms, as well as identify worthy picks for the foreignand global- stock versions of the strategy—

Some of these companies make it into the domestic portfolio as well because, as Gleicher puts it, these are “unique and compelling businesses that happen to have headquarters outside the U.S.” In the Aristotle Value Equity fund, foreign exposure is limited to 20% in the form of ADRs and is generally under 15%. The overlap between the two funds was less than 10% at the end of September, and included

Sony is an example of how the deliberative process works. As Gleicher describes it, the team bumped into Sony at every turn in the course of researching other investments. They had a stake in Vivendi in the global strategy, and Sony’s music group was a big competitor. They own

“After several years of work, we chose to make this investment,” Gleicher says. “In every analysis, Sony was a very formidable competitor, in many cases, more formidable than the original company we were researching. There were some unique catalysts, and the management team is very shareholder-friendly.”

Steady Performance Padilla contends that Aristotle's combination of value and quality leads to good performance in both up and down markets. "We encourage clients to measure our performance on three- and five-year rolling periods, the way we look at the companies we invest in— not every quarter, not every year, but over long periods of time."

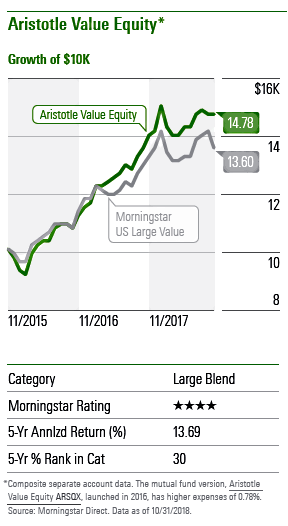

The mutual fund version of the strategy doesn’t have a long enough record to evaluate by that standard. Since its August 2016 inception, it has had mixed results against the two benchmarks management holds the strategy against, the S&P 500 and the Russell 1000 Value: It lags the former through October, but beats the latter. That’s too short a record to support broad conclusions, though.

However, Morningstar tracks a composite record of the separate account version that extends to the beginning of 2001—the strategy has been under the Aristotle name since November 2010, but it started under Gleicher’s management a decade earlier. The record holds up to scrutiny. From January 2001 through September 2018, the strategy has 154 five-year rolling return periods, and it beat the S&P 500 over 94% of those periods and the Russell 1000 Value over all of them.

That strategy also earns a Morningstar Rating of 4 stars when evaluated against other separate accounts in the large-cap blend Morningstar Category: While it has shown more downside volatility than have peers over the past decade—likely a reflection of a concentrated portfolio in part—strong returns have more than offset that.

The strategy has also gotten a nod from Morningstar’s manager research analysts. While it does not have an Analyst Rating, Harbor Large Cap Value HAVLX—subadvised by Aristotle, with Gleicher and Padilla at the helm— is included in Morningstar Prospects, a list of up-and-coming or under-the-radar investment strategies that Morningstar Manager Research deems worth watching. The report cites the fund’s solid absolute and risk-adjusted performance since Aristotle took over in 2012.

It’s important to note that the separate account record does not reflect the level of fees that would be paid by fund investors. That said, reasonable expenses (0.68% for the institutional shares of the Harbor version of the fund and 0.78% for the Aristotle version) improve the funds’ odds of continued competitive performance within their mutual fund categories.

“Nothing is guaranteed in this business,” Padilla says, “other than that we are going to give our best.” That said, history suggests that shareholders can reasonably expect consistent application of this established, low-turnover approach, as well as continuity on an investment team with a vested interest in the firm.

“One of the beauties of the boutique environment here is that, while we meet formally, we also spend a lot of time offline just talking about companies. It’s a very curious, collaborative, and collegial environment,” Padilla says. “There’s an expectation that you love what you do and are self-motivated.”

Says Gleicher, “I am blessed in that my business life and personal life are closely intertwined. Some of us have been together for 30 years in a couple of different iterations of the business. When we’ve had to move our team, almost everyone came along. It’s a testament of the enjoyableness of the workplace: We work together to help everyone succeed, including clients. Having financial security so you can spend time with your children and grandchildren, that’s the goal.”

This article originally appeared in the December/January 2019 issue of Morningstar magazine. To learn more about Morningstar magazine, please visit our corporate website.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/6bbc8215-6473-41db-85a9-2342b3761e74.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WJS7WXEWB5GVXMAD4CEAM5FE4A.png)