A Close Examination of the Risks and Rewards of Securities Lending

This practice has come into sharper focus as index funds’ and ETFs’ fees have fallen.

Index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds are natural lenders of stocks and bonds because they offer a broad and stable inventory of securities. In fact, many lend portfolio securities to generate additional income, which can improve these index portfolios’ tracking performance. Fundholders stand to benefit from additional income that can offset fund costs.

Securities lending income isn't all gravy--it carries some risk. The global financial crisis brought these risks to the fore. During this period, a handful of funds incurred losses from their securities-lending programs [1]. However, securities lending is less risky today than in the past. All told, we believe the benefits of securities lending to fundholders outweigh the risks.

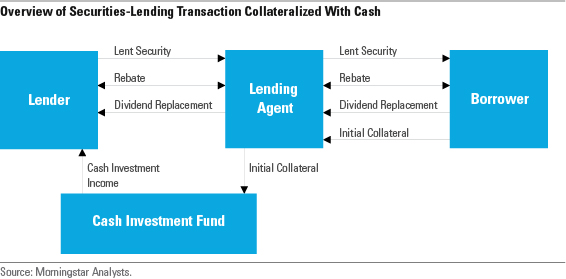

Mechanics of Securities Lending Securities lenders are typically institutional investors with long investment horizons such as retirement and pension funds, registered investment funds, government bodies, and insurance companies. Borrowers include broker-dealers and hedge funds, which usually borrow securities to short, avoid settlement failure, or profit from arbitrage opportunities. Lending agents take a cut of the lending revenue in exchange for matching lenders and borrowers.

Lenders generate revenue by charging borrowers a fee. Supply and demand dictate fee levels. In the United States, small-cap and international stocks usually command a higher fee than large-cap U.S. stocks because they are more difficult to locate and borrow in the market. On the demand side, popular shorts command higher borrowing fees and are usually referred to as "on-special" or "hard-to-borrow" securities. In 2018, examples of on-special securities included

To mitigate the risk of borrower default, lenders require borrowers to post collateral of greater value than the lent security. Lenders mark collateral to market daily. Collateral can come in the form of securities (U.S. Treasuries and agency debt for 1940 Act funds) or cash. Exhibit 1 shows exchanges between the lender, lending agent, and borrower in a

lending transaction collateralized with cash.

Not-So-Risky Business

There are two primary risks of securities lending: borrower default risk and cash collateral reinvestment risk. Borrower default risk is the risk that the counterparty fails to return the borrowed security back to the lender. Borrower default risk is the lesser of these risks because loans are generally overcollateralized to the tune of 102% for U.S. securities and 105% for international securities. Lenders can also call back securities on loan at any time, and the SEC limits the percentage of securities on loan to one-third of fund assets. Some lending agents offer indemnification from counterparty default losses. But defaults are rare, and their impact is usually negligible thanks to the

.

How the agent invests cash collateral is a larger source of risk. If it's reinvested too aggressively and the risk-taking results in losses, then the fund may suffer losses. This exact scenario is what resulted in securities-lending related losses among some funds during the financial crisis.[2] Parties that participated in securities lending (mostly endowment and pension funds) were stuck with the losses from reinvesting cash collateral after their lending agents had reaped their cut of the revenue for years.[3] This also affected several 1940 Act funds. For example, Calamos Growth Fund incurred an $8.6 million loss from cash collateral reinvestment losses from its securities-lending program.[4]

In response to these losses, the SEC mandated tighter credit quality, duration, and liquidity requirements for the securities to be eligible for investment by money market funds in 2010.[5] Today, nearly the entire cash collateral portfolio must be invested in U.S. Treasuries or short-term commercial paper rated AA or higher. These more-conservative rules have largely reined in the cash collateral reinvestment risk faced by mutual funds and ETFs.

How Does Your Fund Company’s Securities-Lending Program Stack Up?

Key characteristics of fund sponsors’ securities-lending programs include the lending

if that agent is affiliated with the fund sponsor, and the agent’s cut of securities-lending revenue. Most fund sponsors report 100% of net securities-lending revenue is passed back to the fund. "Net" is the operative word here. Securities-lending agents deduct fees and sometimes costs associated

the securities-lending program from the gross securities-lending revenue figure.

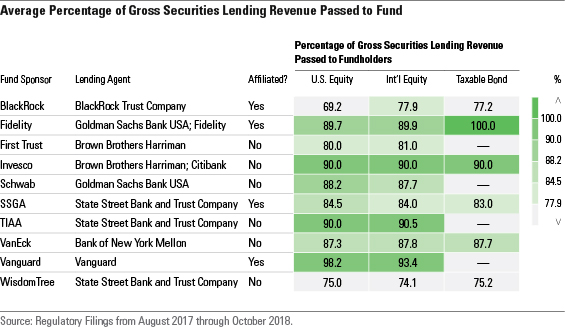

Exhibit 2 presents the key securities-lending program characteristics of the largest U.S. passive fund sponsors. We calculated the average percentage of securities-lending revenue kept by fundholders from a sample of funds’ regulatory filings from August 2017 through October 2018.

The range of the percentages of securities-lending revenue passed along to fundholders varies from 69.2% for the BlackRock U.S. equity funds in the sample to 100% for the Fidelity taxable-bond funds. Most securities-lending agents apply a consistent revenue split across asset classes. For example, Invesco’s securities-lending agents levy a 10% cut of the gross lending revenue. Fidelity and BlackRock take a different tack.

Fidelity uses an unaffiliated securities lending agent, Goldman Sachs, for its equity funds. Fidelity equity fundholders keep about 90% of the gross securities-lending revenue. For its bond funds, Fidelity administers the securities-lending program itself and passes along 100% of gross securities-lending revenue to bond fundholders.

BlackRock uses a tiered pricing system based on asset class and the amount of securities-lending revenue generated. Per the sample above, BlackRock passed along just under 70% of securities-lending revenue to U.S. equity fundholders and nearly 80% to international stock and bond fundholders.

All else equal, sharing a greater portion of the gross revenue generated from securities lending is a better shake for investors. But it is difficult to make apples-with-apples comparisons across fund sponsors using this metric in isolation. Some firms with less generous

consistently generate more total lending revenue by lending more aggressively.

How Much Can Securities-Lending Income Benefit Investors?

Securities-lending income can meaningfully offset a fund’s expense ratio. For example, the average securities-lending income yield

Russell 2000 ETF IWM was 0.19% from March 2007 through March 2018. This nearly offset the fund’s expense ratio, which held steady at 0.20% during this span. IWM investors effectively paid 0.01% annually to track the Russell 2000 Index.

To measure the benefits of securities-lending income to investors over a longer time horizon, we collected a sample of securities lending data from funds’ annual reports. This sample covered the same 10 fund sponsors from 2007 through the first half of 2018. It included nearly 3,000 observations from 440 unique index mutual funds and ETFs across 13 Morningstar Categories.

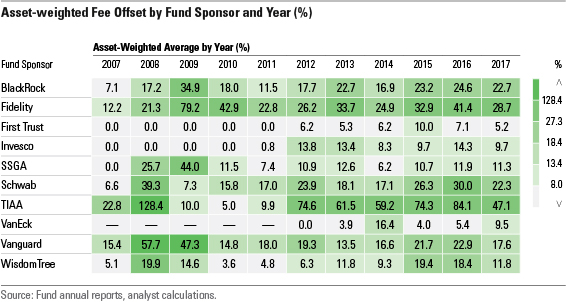

Next, we calculated the portion of

ratio offset by securities-lending income. For example, if the securities-lending income yield for a fund measured 0.19% and its fee was 0.20%, then securities-lending income offset 95% of the fund’s fee. Exhibit 3 shows the asset-weighted average fee offset within the sample of funds.

In this sample, TIAA, Schwab, Fidelity, and BlackRock stand out as doing a good job of offsetting their funds’ expenses with revenues from securities lending. TIAA offset nearly 50% or more of its funds’ expense ratios in this sample from 2012-17. This is partially due to its low expense ratios. It’s easier to offset a smaller fee. As an investor, paying a low management fee with the potential to have that levy offset is not a bad proposition.

That said, firms could also use securities-lending revenue to maintain higher fees. For example, the three micro-cap stock funds in this sample--

Conclusion The benefits of securities lending to fundholders outweigh the risks primarily because the biggest risk, losses associated with cash collateral reinvestment, is low, and now even lower than was in the past. In the U.S., given the conservative requirements for the reinvestment of cash collateral, more aggressively pursuing securities-lending income isn't necessarily riskier.

Differences among securities-lending programs tend to move the needle less than differences among fees and portfolio construction. But if securities-lending considerations play the role of tie-breaker between two nearly identical funds, keep these three things in mind:

1. How favorable is the fee split? All else equal, fundholders stand to benefit more from securities-lending agents that pass along a greater proportion of securities-lending revenue to the fund.

2. How much securities-lending revenue has the fund generated in the past? Although securities-lending revenue is inconsistent, historical data is the best gauge of how aggressive or conservative the fund's securities-lending program may be.

3. How aggressively does the fund sponsor pursue securities-lending income? The preferred approach depends on the investor's risk-tolerance. Some fund sponsors lend only opportunistically, putting on loan only securities that command high lending fees. Others lend out a greater portion of the portfolio regardless of lending fee level. More-aggressive programs aren't necessarily riskier.

Interested readers can find our full-length report on this topic here.

[1] Lambert, E. 2009. "Securities Lending Meltdown." Forbes. June 4, 2009. https://www.forbes.com/forbes/2009/0622/mutual-funds-pension-securities-lending-meltdown.html#2d193fab24b9.

[2] Keane, F. 2013. "Securities Loans Collateralized by Cash: Reinvestment Risk, Run Risk, and Incentive Issues." Current Issues in Economics and Finance. Nov. 3, 2013. https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/current_issues/ci19-3.pdf

[3] Story, L. 2010. "Banks Shared Clients' Profits, but Not Losses." New York Times. Oct. 17, 2010. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/18/business/18advantage.html

[4] Zweig, J. 2009. "Is Your Fund Pawning Shares at Your Expense?" Wall Street Journal. May 30, 2009. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB124363555788367705.

[5] https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2010/ic-29132.pdf

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click

for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets,

or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/64dafa24-41b3-4a5e-aade-5d471358063f.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)