Hedge Funds Look Slightly Better This Year

But they still have not been good enough

Bad Press Hedge funds fascinate me, as they are simultaneously a major business--at last report, 25 members of the Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans made their fortunes running hedge funds--and a cottage industry. Because their reporting requirements are almost nonexistent, hedge funds operate in near secrecy. Their reputations owe as much to whispers as to their accomplishments.

Those whispers have become distinctly unfavorable. "Tough environment has hedge funds heading for the exits," writes Pensions & Investments. States The New York Times, "Hedge funds should be thriving right now. They aren't." Institutional Investor wonders: "Have Institutional Investors Spoiled the Hedge Fund Party?" The headlines, to put the matter mildly, have been unkind.

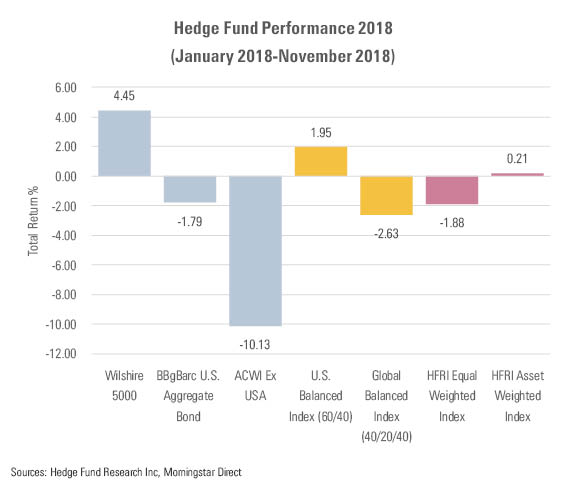

By the Numbers Let's see how the 2018 figures play out. The chart below shows the year-to-date index returns for three conventional asset classes: 1) U.S. stocks, 2) foreign stocks, and 3) U.S. investment-grade bonds. They can be combined to form a U.S.-only balanced portfolio (the fourth bar) or, more realistically, a balanced investment that includes foreign equities (the fifth bar). On the right are this year's hedge fund returns, calculated in both equal- and asset-weighted terms.

The domestic perspective is unflattering. The U.S. balanced portfolio--represented by the first of the yellow bars--finished November up 1.9%, while the stronger version of the hedge fund composite (the asset-weighted calculation) gained just 21 basis points. The weaker version of the composite dropped 1.9%, almost 4 percentage points behind the retail portfolio. With that level of performance, the rich and famous might become only famous.

This evaluation, however, is not entirely fair to hedge funds. Benchmarking them to a balanced allocation is acceptable. As a group, hedge funds invest heavily in both stocks and bonds. (In 2008, the industry's average return matched that of the U.S. 60/40 portfolio.) However, as many hedge funds invest throughout the world, the global balanced portfolio, as represented by the second yellow bar, is the better comparison. When that is done, hedge funds come out moderately ahead for the year to date.

An Upswing? Thus, hedge funds haven't been all that bad. At least through November (the stock market hasn't exactly shone this month), the industry's performance disappoints at first glance, because the immediate, first comparison is with domestic equities, which have been among the globe's better-performing assets. But upon further examination, the results are acceptable. If U.S. stocks are leading the way, the "hedged" investment would be expected to trail, by roughly the margin that it has.

What's more, there's a glimmer of hope with the asset-weighted figures. If assigning the larger funds more importance in the calculation increases the performance by 210 basis points, as is the case, then clearly the select few among hedge funds have outgained the huddled masses. Assuming that an accredited investor can get access to those giant funds--a legitimate question--then the solution to the alleged hedge fund "problem" seems simple. Don't purchase a small, second-rate fund. Buy an elite fund instead.

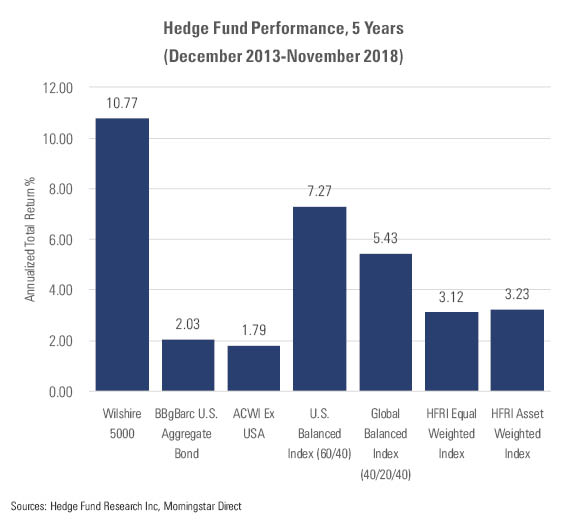

The Bad News That would seem to make sense. Unfortunately, as suggested by the media headlines, which hint that hedge funds' current problems are part of a larger pattern, the longer view undercuts the positive narrative. Hedge Fund Research Inc. (the source for the hedge fund data) provides five-year performance averages in addition to year-to-date measures, and the evidence is damning. This time, hedge funds can't escape their reputational hole.

No matter which hedge fund average one selects, or which flavor of balanced portfolio, hedge funds trail. There's no reasonable way to avoid that outcome. Even cutting the balance portfolio's equity stake to 50% from 60% while upping the foreign-stock position so that it accounts for half the equities (thereby making the overall portfolio 25% U.S. stocks, 25% foreign stocks, and 50% bonds) doesn't give hedge funds the lead. Over the past five years, the hedge fund averages lagged those of a retail balanced portfolio assembled from ordinary index funds.

That hurts. In addition, the asset-weighted defense vanishes. Over the trailing five years, the two versions of hedge fund returns fall almost exactly in line. There was no overall benefit to holding the hedge funds that were alleged to be the industry's best and brightest (again, assuming their doors were open). On average, the obscure funds performed just as well as the ones that were managed by the Forbes list billionaires.

The news gets worse. Hedge fund results, infamously, are strongly affected by creation and survivorship bias. Because they are not legally obligated to announce their returns, hedge funds tend to ring the doorbell when the time is opportune--meaning after strong performances--and to disappear when it is not. Thus, agree onlookers, the averages reported by hedge fund databases are skewed upward. In contrast with the retail balanced portfolios, which returned exactly what they reported, the hedge fund figures are, shall we say, optimistic.

Conclusion As with so many aspects of this long economic recovery, the story for hedge funds has remained broadly similar since 2008 ended. The basic conditions endure.

- There is too much supply. Hedge funds would thrive if they had $200 billion or $300 billion to put to work. Instead, they have 10 times that amount. There aren't enough good, unexploited investment ideas to support that much money.

- Equities, especially U.S. stocks, are among the best-performing asset classes. That has removed the luster from hedge funds' hedging activities.

- Unlike during 2000-02, when hedge funds were largely insulated from the technology-stock downturn, today's hedge funds are exposed to all segments of global equities. They may not prove to be as much of a disappointment as in 2008, but neither are they positioned to repeat their previous relative success.

In summary, although this year's hedge fund showing has been slightly better than in recent years (including in October, when the average hedge fund fell only about one third as far as did the S&P 500), the industry has far to go. Until the next highly disruptive market event occurs, which could shake out the decade-long status quo, it's difficult to see how hedge funds will regain their appeal.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar’s investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)