Intermediate-Term Bond Managers Pull Ahead

Their 10-year total return now exceeds those of index funds.

At Long Last

Morningstar’s Miriam Sjoblom caught my attention. For the first time in since forever, she surmised, the 10-year average return for intermediate-term bond funds was above that of

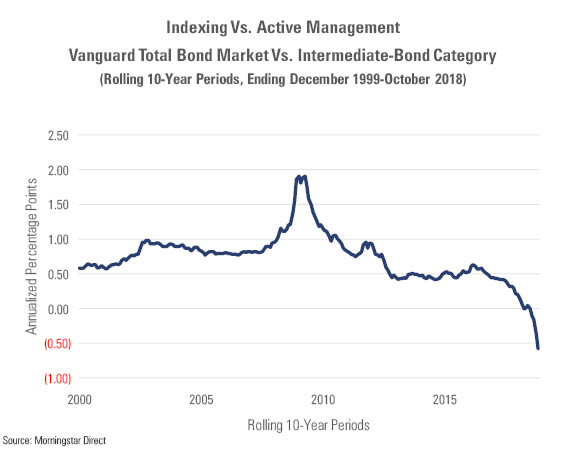

Cleverly, I feigned skepticism, thereby spurring Miriam to run the numbers. She returned, vindicated. As shown below, until this summer, Vanguard Total Bond Market Index had beaten its actively run competitors in every trailing 10-year period since December 1999. In June, though, its relative-strength line crossed into the red, and it has been headed down ever since.

(This is a clean comparison. The category average includes all funds that existed at the time, even if they have since expired, and it adjusts for the number of a fund’s share classes, so funds that possess many share classes are not overcounted.)

Reading It Right Rolling-return graphs are frequently misinterpreted. I have attended several lectures on investment "style drift" at financial-advisor conferences. Inevitably, the presenter shows the evidence from a rolling-return analysis, points to the chart's right and explains how the movements of the past two months illustrate management's recent decisions. The audience then nods--it should not.

With rolling returns, we don’t know when the event occurred. For example, a style-drift analysis based on trailing three-year numbers that shows a decrease in a fund’s international-stock position could have indeed occurred last month. However, it also could be that an unusually large October 2015 stake rolled off the study. Similarly, Vanguard Total Bond Market Index’s travails could reflect recent events, or what occurred in 2008.

Ah yes, 2008. That year. It was, as it turns out, an extraordinarily strong stretch for Vanguard Total Bond Market Index's relative performance. For the calendar year, the index fund gained just over 5%, while the intermediate-term bond Morningstar Category average fell by almost that amount. The result was a 975-basis-point swing in a single year. As long as the fund retained 2008 in its track record, it could trail the category average by a full percentage point in the other nine years of a 10-year period and still finish ahead. In practical terms, it could not lose.

Now it can. It is not as if this fund is performing badly. The apparent collapse of its recent form is just that: apparent. Over the past three months, Vanguard Total Bond Market Index has essentially matched the category average (2 basis points behind), and it’s only slightly behind, at 24 basis points, for the year. The rolling-return chart makes 2018 look eventful, but in truth it’s been routinely dull.

That leads us to three questions.

1. What happened in 2008? You certainly know the first part of the answer. Banks folded, the stock market crumbled, and the bond market froze. Treasury notes traded briskly, but securities not guaranteed by the federal government struggled to get bids. There was, as the cliche goes, a flight to quality.

You may know the follow-up, too. (Miriam needed no prompting.) Unusually among index funds, Vanguard Total Bond Market Index looks very different from its typical competitor. An S&P 500 index fund holds somewhat larger companies than does the average large-blend U.S. stock fund, but the disparity is modest. The index fund will go pretty much where the category goes, only more cheaply. Not so with this fund and its rivals.

Currently, Vanguard Total Bond Market Index invests 41% of its portfolio in Treasuries, compared with 19% for the category average. It makes up for that shortfall by owning issues that, across the board, lagged behind Treasuries in 2008. Sometimes far behind. High-yield debt and commercial mortgage-backed securities, which are barely held by the index, make up almost a tenth of the category’s average portfolio. Those securities lost more than 20% in 2008.

2. Why is the index fund different? Although Vanguard Total Bond Market Index holds the investment-grade U.S. bond market, and most intermediate-bond funds purport to do the same, the index fund is, practically speaking, another species. Those who run intermediate-bond funds--and who are usually paid by how they perform against the index that underlies Vanguard Total Bond Market Index (the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index)--systematically underweight Treasuries. That has been the case throughout the trailing decade.

The positive spin for this decision--the argument that I would make, if I were tasked with selling such funds--is that, in 2008’s aftermath, active managers realized that risk would pay. As the economy recovered, the lower-quality, less-liquid issues that had suffered the most would rebound the furthest, and they would stay ahead until the next recession. Sound thinking, portfolio managers!

Except … that will always be so. Active funds shunned Treasuries before 2008, during 2008, and after 2008. Their stance will not change. They will always hold fewer Treasuries than does the index. Matching the benchmark’s position would make them like the index fund, only pricier. Going further--exceeding the index’s stake--does provide the opportunity for outperformance, during flights to quality. However, those boons tend to be short and swift; on most occasions, such funds will trail. That is not what active managers wish.

3. Which is better: Index funds or the active managers? For a complete market cycle, probably the indexer. I don't see why the answer should vary according to the investment sector. Over time, the decisions of a group of portfolio managers have a roughly neutral effect, which means that the indexer leads by the size of its cost advantage. The analysis becomes more complicated if the index fund holds a somewhat different portfolio than the category average, as in this instance, but the general point remains. Index funds have the advantage unless Treasuries prove to be long-term relative losers.

Shorter periods are anybody’s guess. Active funds are now ahead for the decade, and they may well retain their lead until the next recession. I would not bet against them. But were I in the market for an intermediate-term bond fund, I would not bet on them, either. It has been a long time since 2008. I doubt that it will take Treasuries another 10 years to show their virtues.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)