The Mutual Fund Industry Is Shrinking. And That's OK.

Fewer, cheaper funds are better for investors (and, long-term, for the industry, too).

After growing steadily for nearly two decades, the number of open-end mutual funds has shrunk in recent years. Fund companies are launching fewer funds than usual but folding them faster than before, explaining the contraction. This is a welcome development insofar as it should gradually cull smaller, pricier funds from the industry, leaving investors with a less-daunting, cheaper set of funds to choose from.

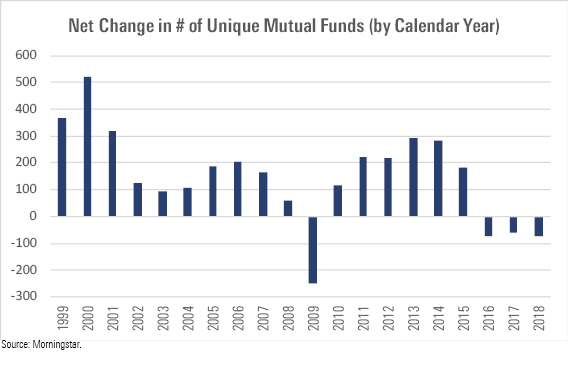

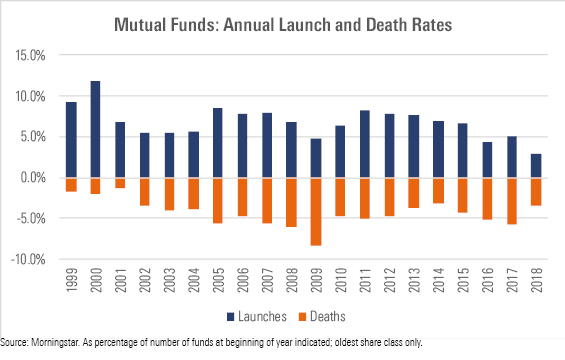

The Industry Is Shrinking There are about 2.5% fewer mutual funds today than there were at the end of 2015. Fund companies launched a total of 954 new funds in 2016, 2017, and thus far in 2018. But that was more than offset by the 1,161 funds they merged or liquidated away over that span, for a net reduction of 217 funds.

That might not sound like much, but it’s significant: The fund industry had expanded pretty much like clockwork from 1999 through 2015, with the number of funds ballooning to 8,138 from 4,919 over that 16-year period. Yet, with investors leaving active funds for passives in droves, that’s throttled new product development. All told, fund companies are launching about half as many funds as they used to while putting the kibosh on funds more often than before.

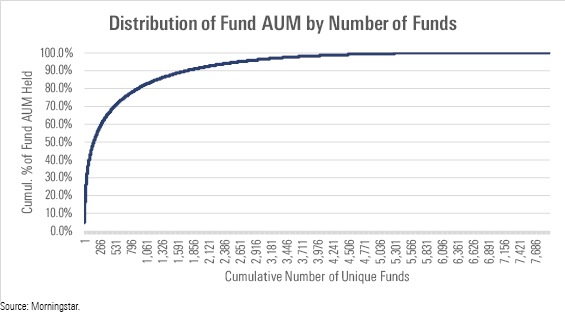

And That's OK That's good. There are too many funds--in all, 7,938 unique funds remain available to investors. Of those, nearly 2,800 have $100 million in net assets or less, 1,900 have $50 million or less, and 655 have $10 million or less. The top 160 funds by size account for 50% of industry assets under management, the biggest 429 for two thirds of assets, and the largest 919 for 80% of assets. If the smallest half of funds were shuttered, it would affect only around 1.8% of industry assets; if the smallest three fourths of funds fell under the ax, less than 10% of overall AUM would roll.

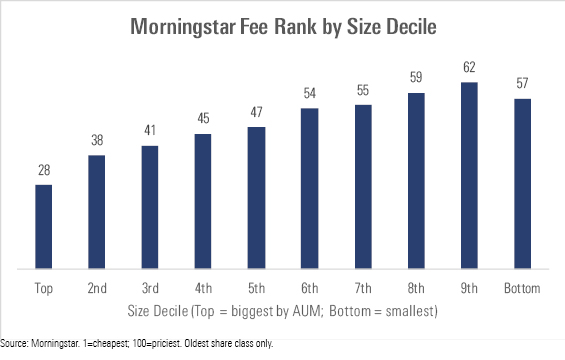

These funds in the long tail aren’t just small--they’re expensive, too. Sorted by AUM, the smallest 70% of funds levy meaningfully higher fees, as evidenced by the fee ranks shown (the cheapest funds get the lowest numerical fee ranks; the priciest get the highest). Cost has driven demand in recent years, so these undersized, pricey funds are increasingly finding themselves on the outside looking in.

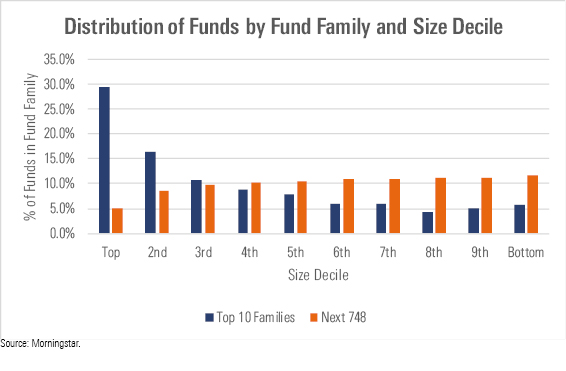

While it’s true that some of these smaller, pricey funds hail from the 10 largest complexes by assets, most come from smaller fund families. As shown in the chart below, the top 10 fund families by AUM are heavily represented in the first three size deciles, while the next 748 families by assets account disproportionately for the funds in the smaller size deciles. Thus, it appears there’s a glut not just of small, costly funds but also of the smaller fund families that are home to them. Many of these firms will likely need to trim expenses, join forces with rivals, or exit the business altogether.

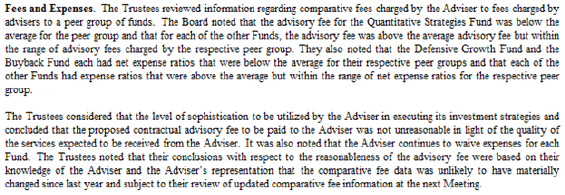

Investors Win This shakeout should benefit investors in a few ways. First, as marginal players exit, there's less clutter and, thus, less risk of choice overload. Second, it could help to arrest the cycle of rationalization by which fund fees are often set. To explain, in the normal course of assessing fees, fund boards will often compare the price tags of the funds they oversee with those of other funds in a custom peer group they've created. The problem? The custom peer groups the board assembles can sometimes teem with pricey funds, which makes the comparisons easier. To illustrate, consider the following excerpt from the annual report of a fund in which the board assesses the competitiveness of its fees.

The "Buyback Fund" referenced is AmericaFirst Quantitative Large-Cap Share Buyback, an active large-blend fund whose cheapest share class costs 1.50% per year. This, in a category where one can literally invest in large-cap stocks for nothing. Despite that, the board asserts that the fund's expenses are "below the average" for its unspecified peer group.

As this example makes vividly apparent, boards not infrequently set fund fees in relation to other funds. This process can be mutually reinforcing for the worse because pricey funds like this one become part of some other board's custom peer group and, thus, a justification to levy high fees elsewhere. But if the pool of costly funds shrinks over time, it'll be harder for boards to engage in this sort of artful rationalization in the future.

Funds Win? No, it's not reasonable to expect fund companies to jump for joy at seeing their industry shrink amid price and competitive pressures. But the reality is that many funds are priced to fail, levying expense ratios that leave them little hope to beat a comparable index fund or exchange-traded fund. (This is truer of equity than bond funds, with the latter enjoying greater success versus passive funds than the former.)

The silver lining is that industry consolidation and fee rationalization is likely to make the remaining active funds that much more competitive after fees. True, it wouldn’t change the immutable laws of active investing--namely, no more than half of active dollars should be expected to beat the market before fees and less than that after fees. But it should make success less elusive than it has been, perhaps lifting investors’ sagging confidence in the process.

Final Thoughts The number of mutual funds appears to be shrinking, with launches not keeping pace with mergers and liquidations in recent years. This is probably healthy, as it will help to cull the industry of smaller, costlier funds that investors have shown scant interest in to begin with. As that trend continues to take shape, investors are likely to face a less daunting and expensive set of options.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)