How Exposed to Italy Are Index Funds?

Political drama in Southern Europe has gotten markets unnerved once again.

Italy’s budgetary plans for the 2019 fiscal year have unnerved financial markets. The Lega/Five Star Movement governing coalition, which came into power with the promise of a comprehensive program of extra public expenditure, has approved a substantial upward revision to the 2019 budget deficit target to 2.4% of gross domestic product: 3 times higher than the 0.8% figure agreed by the previous administration with the European Commission. The deficit targets for 2020 and 2021 are 2.1% and 1.9%, respectively.

To say that EU authorities are displeased would be an understatement. Yields on Italian bonds, which had been on a rising trend since the installation of the populist administration, have shot up further, sparking fears that an open confrontation between Rome and her eurozone partners could be the beginning of another systemic crisis for the euro.

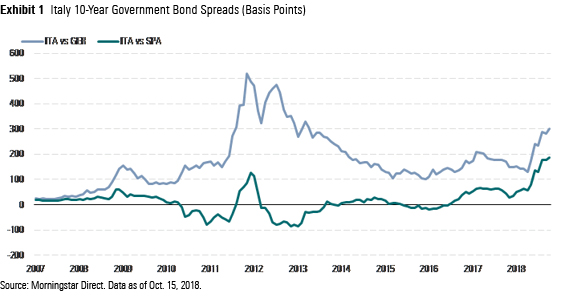

So far there has been little sign of contagion. The spread between German and Italian bonds has widened but, crucially, so has that between Spain and Italy (see Exhibit 1). This indicates that financial market participants have focused the selling pressure on Italy alone, pricing in the mounting risk--inevitable for some--that Italy’s sovereign rating will be downgraded. At present, Italy is rated just two notches above non-investment-grade by the three major rating agencies (S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch).

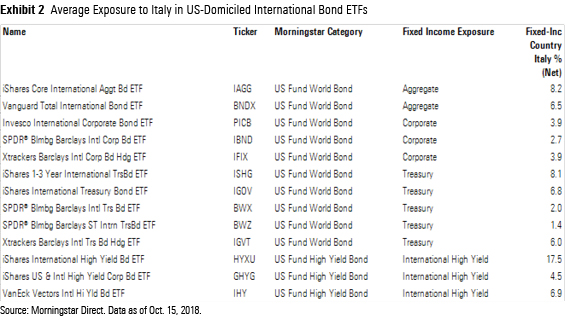

Italy Is a Large Holding in Fixed-Income Passive Funds The lack of contagion to other peripheral eurozone issuers, while welcome, should not lull investors into a false sense of security. Italy's problems on their own do matter--a lot, in fact. Italy has the largest government bond market in the eurozone and the third largest in the world after the United States and Japan. This means that passive funds providing exposure to international sovereign bond markets, which for most U.S.-based investors are a tactical investment, can have a large weighting in Italian bonds.

Negative sentiment in government bonds can easily spill over to other areas of the fixed-income market, such as corporate and high yield. Therefore, when assessing exposure to Italy, one should take a broad view. For example, the weight of Italy in

Will My Passive Fund Become a Forced Seller of Italian Bonds? Holders of passive funds with a large exposure to Italian government bonds are rightfully concerned about the practical implications of a sovereign rating downgrade in the day-to-day management of the funds. Typically, developed sovereign bond market passive funds track benchmarks that require issuing governments to be rated investment-grade. This means that a downgrade of Italy to junk would turn the funds into forced sellers at the worst possible time. Given the large weight of Italy in these indexes, it is easy to imagine a situation where downside pressure to prices is magnified by the sheer volume of bonds that these passive funds--and active funds unable to invest in non-investment-grade debt--would have to shed and, thus, the cost that investors would have to bear.

Besides, a downgrade to junk would also mean that the European Central Bank may be technically barred from coming to the rescue, which would add fuel to the anti-euro rhetoric of this Italian government. In that situation, “Italexit,” that is, Italy abandoning the single currency, may no longer feel like the empty threat that it currently is.

As mentioned, Italy is still two notches above non-investment-grade, and rating agencies rarely bring ratings down by more than one notch in a single move. But more important, a downgrade to junk by just one rating agency would not lead to the expulsion of Italy from the benchmarks, at least not from the most popular ones (Bloomberg Barclays, Markit iBoxx, and FTSE MTS) that ETFs and index funds typically track. For these indexes, the investment-grade-rating eligibility criterion is defined as the average rating from the three main rating agencies--in effect meaning that at least two rating agencies would need to downgrade Italy to junk for it to be dropped and passive funds to be forced to reconstitute their portfolios.

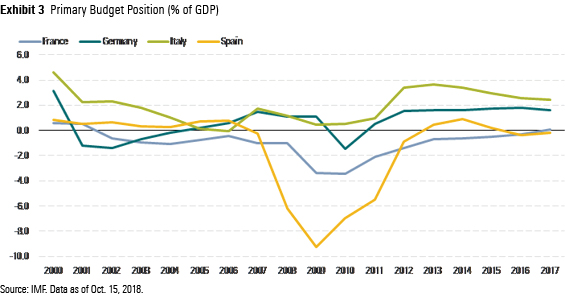

While a downgrade to just one notch above non-investment-grade looks likely--at least from one of the rating agencies--chances of a downgrade to junk status do not seem high at this juncture. For all her ills--and there are quite a few--Italy’s ability to generate sizable budget primary surpluses remains a key factor in her favor. The primary budget position is the difference between tax revenues and public expenditure net of interest payments on debt. This is a key measure to assess public debt sustainability. As Exhibit 3 shows, even in the years since the introduction of the euro and through the worst years of the global economic crisis, when Italy’s economic growth has been pretty much absent, the primary budget position of Italy's public accounts has been routinely in surplus. In fact, it has been the most stable of the big eurozone four. Italy’s public debt burden is certainly high, but it would have been much higher if the government had had to borrow just to settle bond interest payments. And while no one doubts that Italy needs economic growth, it pays not to lose sight that arriving at a sovereign rating decision is a much more complex process that simply looking at GDP growth figures.

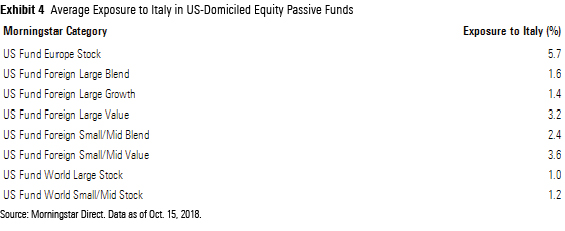

Negative Sentiment Can Spread to Other Italian Assets; Financials Most at Risk Even if Italy being downgraded to junk feels like a tail risk, the losses already incurred--and those that may come--by such an important sovereign bond holding are not to be dismissed lightly. Indeed, sustained negative sentiment on Italian government bonds can easily drag down other Italian assets--both bonds and equities. Typically, corporations pay a premium over domestic government bonds to borrow in the open market, and so any worsening of financing terms (that is, higher yields on corporate bonds) would weigh on stock valuations. Most at risk would be Italian banks, as they are large holders of domestic government debt. The average weight of Italian stocks in a Europe stock passive fund is close to 6%, while in world equity funds the highest weight is in those with a value tilt (see Exhibit 4).

Investors should keep a close eye on Italy for the time being. It is an important economy with a large weighting in bond and equity indexes. We may have to get used to periodic episodes of financial market volatility caused by the blustery utterances of her ruling politicians. However, it is important to not lose sight of the bigger picture to realistically assess investment risk, particularly in relation to the fundamental issue of euro membership.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/09d76e7e-ac49-4fd9-a964-0167c5d46d86.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/09d76e7e-ac49-4fd9-a964-0167c5d46d86.jpg)