The Financial Times Is 'Alarmed' by the U.S. Retirement System

The FT’s portrayal of a decaying American retirement system looks to be off-target.

In Dissent Last month, Financial Times published a wide-ranging article titled "Legacy of Lehman Brothers is a global pensions mess." Among other things, it contended that "the evidence from the U.S." on defined-contribution retirement plans, such as 401(k)s, has been "alarming." The FT advocated that countries with traditional pension systems continue doing so, lest by switching to 401(k)s they create "even greater problems."

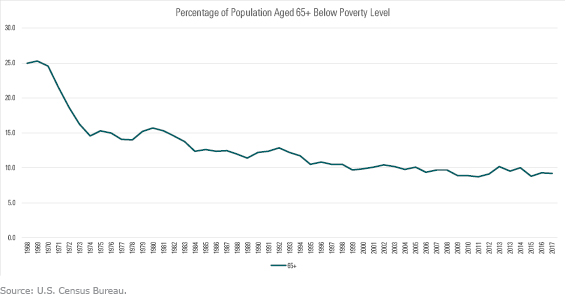

One would think, per the FT's comments, that the American elderly have become poorer. Not so. For Americans aged 65 years and higher, the 50-year trend in the U.S. poverty rate, as provided by the U.S. Census Bureau, has been down, down, down. The current rate is less than half of when Richard Nixon took office and about 40% lower than on the date of Ronald Reagan's inauguration.

Age Before Beauty? That picture alone does not invalidate the FT's argument. Perhaps retirees have improved their absolute fortunes but not their relative ones. If all American age groups had slashed their poverty rates, with seniors advancing the least, then one could reasonably suggest that the U.S. retirement system would be to blame because it had prevented American seniors from benefiting fully from the rising tide.

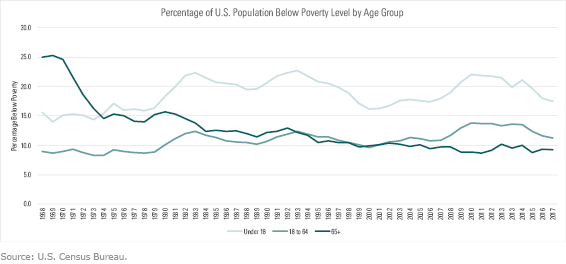

An apparent strike two. The Census Bureau also publishes poverty rates for children (under age 18) and working adults (ages 18 to 64). Relatively speaking, seniors have demolished both groups. As shown by the darkest line below, seniors were the poorest of the three age categories in 1968. They surpassed the children in the 1970s, then working adults 30 years later. Without question, retirees have been the United States’ financial winners.

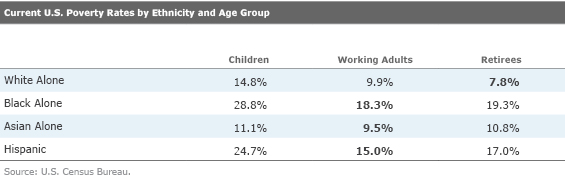

Considering Ethnicity Once again, though, the numbers require further examination. They are for the entire U.S. population, meaning that they are affected by demographics. If, for example, white Americans have lower overall poverty rates than do other Americans, and white Americans tend to live longer, making up a higher proportion of retirees than of other age groups, then those favorable senior poverty rates would be something of a mirage.

Or it might be that the pattern for white Americans differs from those of the other ethnicities, but, because whites account for most retirees, their results dominate. The figures appear to describe the overall American experience, but in fact they describe only the majority segment.

As it turns out, all these things are true. White Americans do have lower poverty rates; they do account for a higher proportion of seniors; and they are the largest of the ethnicities. Those factors make the retiree poverty rate look better than it otherwise might. As shown below, for each of the three non-white retiree groups, the poverty rate is in double digits and higher than that of working adults (although still better than that of children).

(The Census Bureau has a bewildering number of ethnic descriptions. For example, people who consider themselves white can answer: 1) white alone, 2) white, 3) white alone, not Hispanic, 4) and white, not Hispanic. I have no doubt that respondents are utterly confused, as I was at first glance, and then at my second and third glances. Eventually, I settled on white alone, Asian alone, and black alone, which seemed to be the most representative categories.)

However, while this additional information shades the picture, it does not alter it. Today’s black, Asian, and Hispanic retirees suffer higher poverty rates than do their working-adult peers, but, as with white seniors, they have come the furthest. That black retiree poverty rate of 19% looks unattractive--but it is far better than 1965’s calculation of 65%! Across all ethnicities, senior Americans have most enhanced their finances.

Thus, when viewed from on high, the FT’s portrayal of a decaying American retirement system looks to be off-target. Five million older Americans are officially in poverty, and many others feel unofficially so, but there’s no evidence from U.S. Census Bureau statistics that things are getting worse. On the contrary.

Establishing Context It will be objected that if American retirees are indeed better off than during the "golden days," that has little to do with 401(k)s. After all, seniors lowered their poverty rates most dramatically during the 1960s and '70s, before 401(k)s were invented. Similarly, when they pulled ahead of working adults 30 years later, government retirement schemes mostly consisted of traditional pensions. Even within corporate plans, 401(k) assets were barely larger than those of pensions. It would seem that 401(k)s have been credited for others' accomplishments.

By and large, that counterargument is fair. Many factors besides the retirement system affect seniors’ poverty rate: for example, healthcare costs, real estate values, and the vicissitudes of the financial markets. The same also can be said about poverty rates for the remaining two age groups, which affect the relative comparisons. Retirement readiness contains many moving parts; to emphasize just one, while skipping over the others, is to overstate the case.

Which is my point: When discussing the U.S. retirement system, the FT placed too much importance on 401(k) plans. Its caution against moving from defined-benefit to defined-contribution plans was based on a single data set: a 2016 survey of working adults’ retirement assets. Viewed alone, unaccompanied by either historic trends or supplemental information such as expected Social Security income, marital status, homeownership, and possible pension payments, that survey has limited value. It is too flimsy to support the FT’s conclusion.

In short, while 401(k)s cannot be credited for America’s improved retirement outcomes, neither can they be blamed for what has not yet occurred. To be sure, the survey cited by the FT does raise concerns. Some segments of workers are far better prepared than others. This, however, is not news. The American retirement system has long been so structured.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)