How Yield Differs From Income

One represents today, the other tomorrow.

Considering Payouts This column addresses a venerable subject: How payouts from investments are measured. Typically, such payouts are thought of as yield: the cash that securities currently generate. That is the logical starting point; if one were to calculate only a single payout measure, yield would be it.

It is not, however, the ending point. A successful purchase may increase its payouts over time, while an exceedingly poor one will default, thereby ceasing to produce any payments. The latter case, everyone appreciates. Fear is a highly effective instructor. But the former receives less attention. Many investors who seek payouts do so simply by selecting the highest-yielding security that meets their minimum credit standards. Growth is never a consideration.

That can be a fruitful approach. There is a place in portfolios for high-paying investments that will maintain their distribution rates but not increase them. (I own two myself: Invesco Financial Preferred ETF PGF and ClearBridge American Energy CBA.) However, it is not the only way to invest for distributions--and in many cases, not necessarily the best.

I was reminded of this when talking to a coworker.

His father was well off, receiving a pension that met his daily needs and owning in addition an investment portfolio. What he should have done was buy as much equity as his risk tolerance would have permitted. Holding stocks would have given him the chance to increase his future payouts, and he would not have been forced to sell inopportunely, as he did not need to tap into that principal. Instead, his father put everything into currently high-yielding issues (mostly bonds and alternatives).

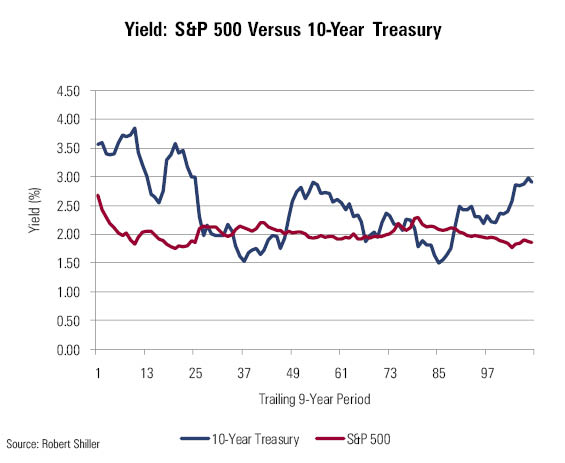

Money Now The chart below suggests his thinking. It compares the monthly dividend yield for the S&P 500 to the coupon yield on 10-year Treasuries over the nine-year period since summer 2009. (The data come courtesy of Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller.) The two yields have, for the most part, been comparable. So why hold risky stocks, when the same income could be gathered from bonds that enabled one to sleep at night?

(The relationship between stock-dividend payouts and Treasury yields has changed greatly over time. One would think the two items would be linked, such that when one rose, the other would rise in tandem. Not so. Through the middle of last century, stock-dividend rates were routinely higher than Treasury yields; then they declined, so that by the mid-1990s they were far lower. Now, the two live in the same general neighborhood, albeit with much fluctuation.)

Both lines are jagged, because the yield calculation uses as its denominator the security's (or index's) market price. Whether that volatility is relevant depends on the context. It matters greatly at the entry point. Somebody who invested $100,000 in the 10-year Treasury at the start of this period (July 2009) would have received $3,560 per year. The unfortunate investor who waited 15 months would have gotten just $2,540. That makes for over a $10,000 difference over the life of the investment.

The volatility also matters for withdrawals, albeit in reverse. While buying Treasuries in summer 2009 would have created relatively fat payouts, selling them would have resulted in relatively lean receipts. Similarly, investors who held tight in summer 2009 when yields were relatively high, then sold in late 2010 when yields were lower, would have done well. Transactions make volatility meaningful.

However, as stated, my coworker's father had the luxury of flexibility. In putting his money to work, he could do it gradually, to reduce the risk of entering at the wrong time. And he need not have removed those assets at all. Thus, he could largely have ignored yield's denominator. The key item for him should not have been the behavior of the market, but instead what happened to the numerator.

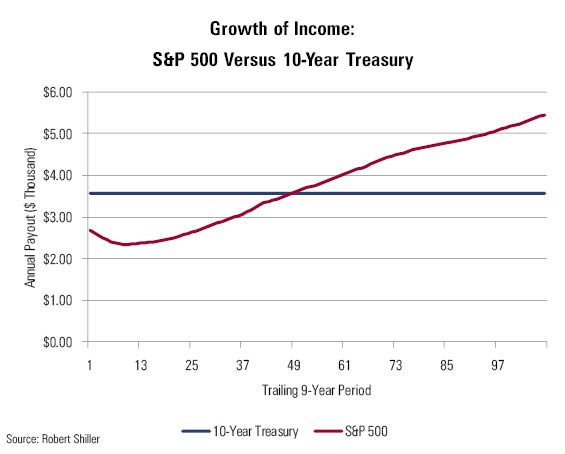

Money Later As it turns out, the numerator takes a much steadier path. The chart below depicts the growth of income for the two investments on a $100,000 initial outlay. There is no growth for the 10-year Treasury. Each year, it pays the aforementioned $3,560. In contrast, the stock market's distribution steadily increases, beginning at $2,674 and finishing at $5,449.

For the nine-year period, the income created by the two strategies was roughly equal. Stock dividends were slightly higher than Treasury-note payments, overall, but as the note's advantage occurred in the early years, the time value of those monies leveled the field. Call the contest a draw. From this point forward, however, it appears that the slaughter rule should be invoked. Stock dividends would need to decline by 40% for the equity investor's income to match that of the Treasury owner, and that is very unlikely. Even the 2008 financial crisis knocked dividends down only by 25% from peak to trough.

It will be protested that I massaged the findings by beginning these charts at the stock market's bottom, thereby making it a nine-year analysis rather than the more-natural 10 years. That is true, but not quite in the manner intended. As previously stated, the behavior of the stock market was beside the point. The dividend-income chart that starts in summer 2008 looks much the same. What changes is the Treasury-note yield, which exceeded 4%--higher than at any time since. I did not think it reasonable to conduct a study that implicitly assumed perfect investor timing!

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CGEMAKSOGVCKBCSH32YM7X5FWI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/LUIUEVKYO2PKAIBSSAUSBVZXHI.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)