The Case for Multifactor Funds

Investors are likely best served by not putting all their factor bets in one basket.

The case for multifactor funds is essentially the case for diversification, which Nobel Prize winning economist Harry Markowitz has described as the only “free lunch” in investing. Investors shouldn’t put all their “eggs” in one factor. But just because the argument for factor diversification is simple doesn’t mean that selecting and sticking with a multifactor strategy is easy. In fact, in light of the proliferation of multifactor funds, choosing from the now-expansive menu is becoming more difficult by the day.

Multifactor Funds Are Multiplying The number of multifactor funds has mushroomed. As of May 31, 2018, there were 300 U.S.-domiciled index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds that were assigned the multifactor strategic-beta attribute in Morningstar's database. [1] A total of 199 of those 300 were launched in the preceding five years. Assets in these funds have grown commensurately. As of the end of May 2018, their collective assets under management stood at $63.9 billion. Ten years ago, this collection of funds collectively held just $2.2 billion of investors' money. Much of this growth has been organic. Over the decade through May 2018, these funds amassed an estimated $49.3 billion in net new flows.

All by Myself Academics and practitioners have documented hundreds of individual factors, though few are widely accepted as being credible. [2] By our count, the ones that best hold water amount to five: value, momentum, size, quality, and low volatility. Each of these factors has been vetted by multiple scholars and professional investors. Many are present across asset classes and in different markets around the world. They have been subsequently tested out of sample and still pass muster. They are, in a word, legit.

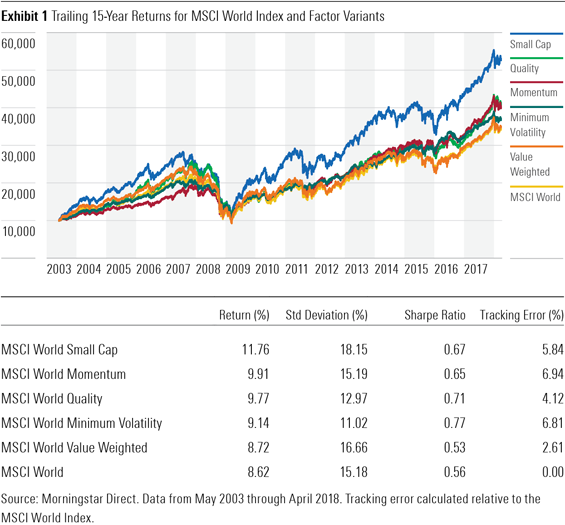

Exhibit 1 shows the performance of some of these factors in a long-only implementation as represented by their corresponding variants of the MSCI World Index during the past 15 years. Over this span, each of these indexes has outperformed its market-cap-weighted parent. Furthermore, all but one of them also produced superior risk-adjusted returns, as measured by Sharpe ratio. Are these factors a free lunch? Hardly.

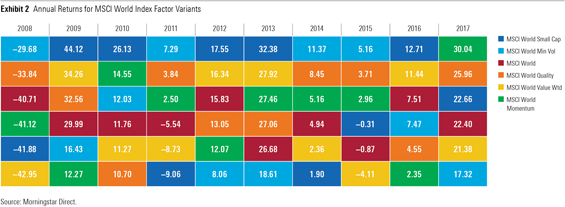

What Exhibit 1 doesn’t adequately depict is the cyclicality of these factors’ performance. While each of the factor variants of the MSCI World Index delivered better absolute—and in most cases risk-adjusted—performance relative to their parent benchmark during the period in question, it was not smooth sailing. This is apparent in Exhibit 2, which is a “quilt” of these factor indexes’ calendar-year returns over the past 10 years.

Each of these factors has and will continue to experience its own unique cycles. Stretches of marketbeating performance will invariably be followed by prolonged droughts. For example, value—as defined here by the corresponding variant of the MSCI World Index—is in the midst of a decade-long dry spell during which it has lagged the market by a wide margin.

One piece of data that is also useful as a crude proxy for this cyclicality is each factor’s tracking error relative to its parent index. The further, on average, the performance of each factor index strays from that of its parent, the more discomfort an investor might experience. If past behavior is any guide (I think it is), then discomfort will often lead investors to abandon sound strategies at precisely the wrong time.

Owning a proven factor on a stand-alone basis has the potential to deliver better risk-adjusted returns relative to owning the market, but it is hardly a free lunch. Bouts of underperformance can lead to buyer’s remorse, which in turn can create the risk of bad investor behavior.

Better Together Value, momentum, size, quality, and low volatility are members of the factor "A-Team." In our minds, value and momentum are, respectively, the John "Hannibal" Smith and Bosco Albert "B.A." Baracus of factors. The former is the battle-tested leader of the group, cool under pressure and known to enjoy "cigar butts." The latter is known for being unpredictable and having a short fuse. Each member of this factor A-Team contributes its own unique and complementary talents in a team setting. The key to getting the chemistry right is sensible diversification—pairing factors that zig with teammates that zag under a given set of market conditions.

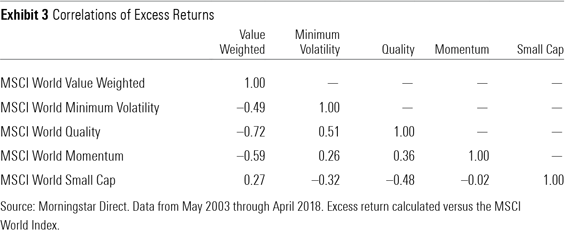

Exhibit 3 is a matrix that shows the correlations of the excess returns among the factor variants of the MSCI World Index that are also featured in Exhibits 1 and 2. It is apparent that some factors, measured strictly in terms of their historical correlations, are more complementary than others. Value and momentum work like peanut butter and jelly, while quality and minimum volatility are more like peanut butter and cashew butter.

Diversifying across complementary factors makes sense. Doing so will mitigate the aforementioned cyclicality associated with owning any one factor in isolation. While this could result in inferior long-term results relative to owning the best-performing factors in isolation, no one knows what those factors will be on an ex ante basis and few have the stomach to stick with them for decades. Perhaps the single most compelling reason to opt for a multifactor strategy is that it will minimize the biggest risk of all: that investors will bail on a factor, manager, or strategy when it experiences an inevitable period of underperformance.

What Matters For most investors, owning a multifactor ETF is preferable to trying to build a do-it-yourself multifactor model, combining single factors on one's own. The "do-it-for-me" approach will likely be more efficient from a cost, tax, and behavioral perspective.

Combining stand-alone factors in a multifactor format is a sensible strategy to the extent that the factors in consideration are 1) credible, 2) well-constructed, and 3) combined in such a way as to improve the overall risk/reward profile of the resulting portfolio relative to owning any of the factors in a stand-alone format.

Portfolio construction matters. It is vital that investors parse the specifics of these strategies to understand their selection universe, how they choose stocks, how they weight them, and the constraints they put in place. Simplicity is likely to trump complexity. The more opaque and overwrought the process, the more likely it is a product of back-testing alchemy and the more likely it may be tweaked should its live performance not live up to its back-tested track record—a record that never looks bad.

Costs also matter. Many of these funds, while competitively priced versus actively managed peers, are more expensive relative to ETFs tracking broad, cap-weighted benchmarks. High fees will ultimately erode long-term gains and should be examined carefully.

Expectations might matter most. These funds are no magic elixir. Many have limited track records. No matter how sensible their process may seem, nor how low their fees, there’s no guarantee they will deliver better risk-adjusted returns than a plain-vanilla cap-weighted index fund over a full market cycle. Much like single factors or good active managers, these funds will experience their own performance cycles (albeit potentially more-muted ones). Ultimately, investors’ ability to reap the prospective rewards these funds might offer is positively correlated to their ability to stick with them through their inescapable ups and downs.

[1] This figure represents the global universe of index-tracking multifactor mutual funds and ETFs and does not include quantitative active equity funds.

[2] Harvey, C.R., Liu, Y., & Zhu, C. 2015. “…and the Cross-Section of Expected Returns.” https://ssrn.com/abstract=2249314 or http:// dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2249314

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/a90ba90e-1da2-48a4-98bf-a476620dbff0.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/09-25-2023/t_f3a19a3382db4855b642d8e3207aba10_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/a90ba90e-1da2-48a4-98bf-a476620dbff0.jpg)