How to Start Teaching Your Kids About Money

And why you should start today.

By Samantha Lamas

By the time the kids leave home, most of them are going to be at least partially on their own financially. Some of them will be completely on their own. The sad reality is that, in most cases, kids leave home without proper financial skills to achieve financial well-being. We see this in the endless cycle of financial mistakes in every generation.

There are many contributors to these mistakes, but a prominent one is our cultural tendency of not talking about money. When it comes to preventing our children from making the same money mistakes we've made, we must start talking to them about money. In "Financial Turning Points: The Parent's Dilemma" Sarah Newcomb, senior behavioral scientist at Morningstar, discusses some techniques that advisors and investors can use to start tackling this complex topic with their children.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly In her research, Newcomb studies psychological relationships with money. Although people have complex and emotional relationships with their finances, the moment their kids are involved in the conversation, feeling words drop out of their language. The same people who talk about money being a source of stress and anger throughout their life will suddenly start speaking in sterile language, describing money as a "useful medium of exchange," even though the emotional aspect of financial decisions can be what kids need help with the most.

Many parents may feel uncomfortable allowing their kids to see how much they earn, how much they spend, or how financially secure they are, and this shows in how we communicate with our kids about money. At the end of the day, shielding kids from the emotional side of money decisions or the specific details and numbers involved can put their financial future in danger.

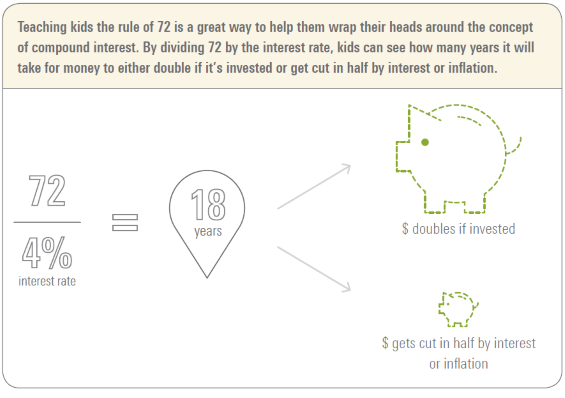

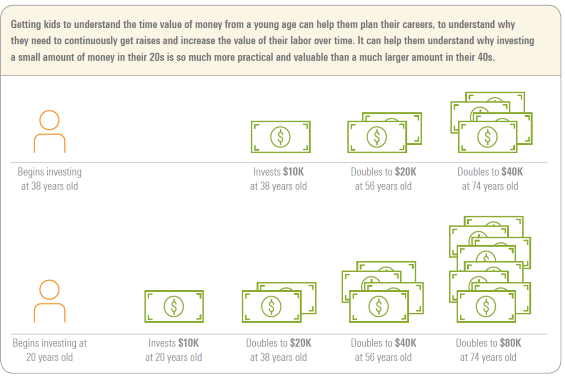

Starting Off Small A great way to start money conversations with kids is by focusing on basic financial concepts. These foundational aspects can and should be taught at an early age. Many key concepts really don't come naturally to most people. A prime example is time perception. Our brains are simply not wired to understand and accurately calculate compound interest, which can result in huge financial mistakes. To help kids avoid these mistakes, parents can start by teaching them the rule of 72 at a young age. Divide 72 by the interest rate, and that tells you how many years it will take for your money to either double if it's invested or get cut in half if you're talking about paying interest or inflation.

Parents can go over this rule at age 8, and then again at 15, and again with a first credit card. As kids grow older, simple rules like this can help them understand why they need to continuously get raises and increase the value of their labor over time. Or even why investing a small amount of money in their 20s is so much more practical and valuable than a much larger amount in their 40s. This simple concept of how long it takes for money to double is easier for our minds to wrap around than the complex computations of compound interest, and the rule of thumb is nearly as accurate as the more detailed equations, so not much is lost by explaining it in these terms.

'Just in Time' Learning Newcomb also recommends a promising strategy that comes from the study of financial education called "just in time" learning. People are the most receptive to new information when it is personally relevant. In other words, you may pay the most attention to information on mortgage loans when you're buying a house.

Parents can take family moments, like when they're buying a new car, and use them this way. They can easily bring the kids into the purchase and help them see everything involved in it. It's the same with buying a home or figuring out the family budget for vacation. Those types of situations can turn into just in time moments that can be very effective and set the stage for your child's further involvement in the family's finances. Helping plan a family vacation budget can evolve into handling the weekly grocery budget, or monthly rent, or any other expense. As their responsibilities grow, kids can begin to understand the biggest thing in money management: Every financial decision is a trade-off.

Another technique is to use the kid's own desires as teaching moments. When your child wants to redecorate her bedroom, give her a budget, and have her shop for the things herself. It will be a powerful lesson in bargain hunting when she is personally invested in the result. Teaching moments arise frequently, and using them to help your kids understand the kind of choices they will need to be making as adults is good practice.

Setting Them Up for Success By the time they leave the nest, children need to be ready to balance major financial decisions for meeting their physical and emotional needs with limited financial resources. And at the end of the day, there's no teacher like experience. Although it may feel uncomfortable to do so, bringing kids into financial decisions early on gives them the experience and confidence they will need later on in life to handle their own finances. Giving them a 'safe place to fail' when they are younger can save them years of anxiety later in life.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/6c608d29-bb89-4580-943a-7819645ad538.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6NPXWNF2RNA7ZGPY5VF7JT4YC4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RYIQ2SKRKNCENPDOV5MK5TH5NY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/6c608d29-bb89-4580-943a-7819645ad538.jpg)