Self-Employed? Determine Your Ideal Hourly/Daily Rate

Factoring your total tax liability into your hourly/day rate calculation can help you stay out of debt and have more money to save.

As if setting up a budget isn't a difficult enough exercise all on its own, being self-employed adds another level of mental gymnastics to the mix.

If you're a salaried employee at a corporation, your taxes have already been removed from your take-home pay. You know that your monthly expenditures--rent, food, utilities, loan repayments (student, auto, credit cards), tuition, child care, etc.--need to total less than your paycheck or you won't be able to make ends meet, let alone save money.

But what if you are self-employed and taxes haven't been taken out of your paychecks? Even worse, what if you can't even accurately determine how much you will owe because your salary is variable depending on how much you work, or what rate you are able to negotiate for a particular job? That's the job we'll tackle today.

Step 1. Estimate your yearly tax liability. A few weeks ago, I wrote about a self-employed friend who wanted to figure out her total tax liability.

My friend Amy is a creative director. Advertising agencies hire her to write ad campaigns. She estimates that for calendar year 2018 her earned income will be in the range of $120,000 to $160,000.

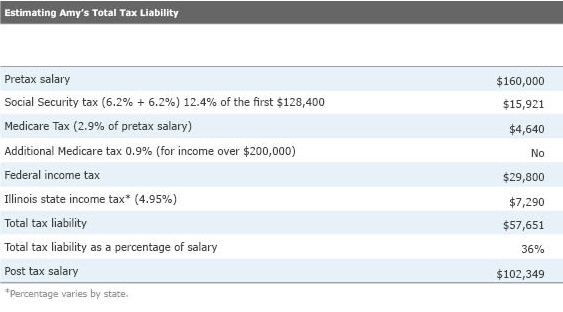

I used the high end of her estimated salary range to estimate her total tax liability:

The first tax is FICA, which is Social Security and Medicare withholding up to the Social Security wage cap of $128,400. (Note that there is no wage cap for Medicare tax.) When you work for a corporation, half is paid by your employer, and you owe the other 7.65% (so the salaried employee's part is 6.2% up to $128,400 plus 1.45% on her whole salary). When you're self-employed, though, you pay both halves.

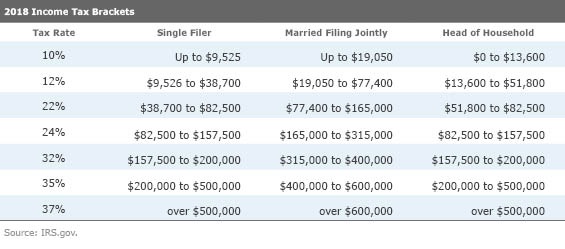

Next, we estimated her federal income tax amount using the tax table below to calculate it.

If you do this exercise yourself, don't simply take your pretax salary and multiply it by your marginal tax rate. For instance, Amy won't be on the hook for 32% of $160,000, even though she falls into the 32% tax bracket. Taxes are paid in tiers. The first $9,525 of income is taxed at 10%. The next $29,174 of income--the amount from $9,526 to $37,950--is taxed at 15%. The next bracket, 22%, goes from $38,700 to $82,500. The next strata of Amy's income, from $82,500 to $157,500, is taxed at 24%. But Amy earned just a smidge more than that--the final $2,500 of her salary is subject to the 32% tax rate, which is her "marginal" tax rate. In actuality, though, her taxable income will be in the 24% tax bracket after we apply the $12,000 standard deduction. Our estimate of Amy's income tax liability is $29,800.

This example is calculated for a single filer. If Amy were married filing jointly, we would need to know about her spouse's income before we could calculate their joint tax liability. For instance, if her spouse were employed by a corporation, we would need to be careful to exclude the portion of the couple's income that had already been subject to FICA tax when calculating their tax liability.

I also added her state tax; Illinois has a flat 4.95% income tax rate.

Step 2: Calculate your post-tax salary. All told, Amy's total tax liabilities will be on the order of 36% of her income, so her budget should be based on 64% of her take-home pay. In other words, though Amy's income totals $13,000 a month, her aftertax salary is more like $8,333; she needs to be careful her monthly expenses don't exceed the tax-adjusted amount.

Step 3: Work the calculation backward to get to your desired aftertax income. From here, I started thinking of other ways we could use this total tax liability percentage. Let's say Amy had monthly expenses of $7,700. Because she earns $8,333 per month after tax, she has only $633 to spare each month. She decides she would be more comfortable earning closer to $10,000 per month after taxes, which would leave her with an additional $2,300 for entertainment, savings, etc.; currently she needs to be sure to save this amount to pay her taxes owed.

We would first determine her desired aftertax yearly salary ($10,000 x 12) = $120,000.

Then we would increase it by 36% to get her desired pretax salary ($120,000 x (1/0.64)) = $187,500.

Amy needs to somehow raise her annual pretax salary by $27,500 to get to $10,000 per month on an aftertax basis. Obviously, she needs to charge a higher rate than she has been. To figure out how much, she would divide the desired pretax salary amount by how many paid hours she works per year to get an applicable hourly and day rate.

For instance, if you work a standard five-day/eight-hours-per-day work week, you would work around 2,080 hours in a year. (Note that about eight of these days are national holidays, plus sick days and/or vacation leave, depending on whether it's paid or unpaid.)

If Amy worked this schedule, she would negotiate an hourly/daily rate of $90/hour or $720/day ($187,500 / 2,080 = $90; $90 x 8 = $720).

If she plans to take an unpaid vacation it helps to plan that in advance and factor it in as early in the year as possible. For instance, if Amy wants to take an unpaid vacation for the month of August she could subtract the 173 paid hours that she would have worked in August from the 2,080 total paid hours and use 1,907 paid hours to calculate an hourly/daily rate of $98/hour or $785/day.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/3a6abec7-a233-42a7-bcb0-b2efd54d751d.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BC7NL2STP5HBHOC7VRD3P64GTU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/3a6abec7-a233-42a7-bcb0-b2efd54d751d.jpg)