Are Economic Predictions Ever Useful?

It is difficult to determine how.

Hindsight Bias Economic predictions are wonderfully useful...after the fact. A fund manager sent back to 1973 and stripped of his investment memories, save for knowing that inflation and commodity prices would soar for many years before subsiding, would thrash his rivals over the ensuing decades. He would be long commodities and short bonds, before switching to stocks in the early 1980s. Toss him a second tidbit--the 2008 housing collapse--and his victory would be complete. His fund would have the best 35-year track record in the business.

One might conclude that our predecessors were dolts. What did the investors of the 1970s think would happen, with a rapidly expanding money supply and oil shortages? Of course inflation would surge. And of course, it would eventually be contained by the Federal Reserve's extreme tightening, under Chairman Paul Volcker. These would seem to be obvious outcomes. (As, per The Big Short, was the future housing crisis.)

Such is how the matter currently appears, since time has cleared the smoke and dust and confusion. History gives a simple picture of that which was once complex. Few who had investment responsibilities when those events occurred found the events to be anywhere near so straightforward. It wasn’t like that.

Yet the temptation to believe otherwise is powerful. (Sometimes I find myself wishing I were old enough to have invested in the 1970s, when the economic signs were so manifest.) Hindsight bias pushes us to rewrite history, to fool ourselves into thinking we can accomplish what others could not. Happily, Merrill Lynch recently published a chart that combats that tendency.

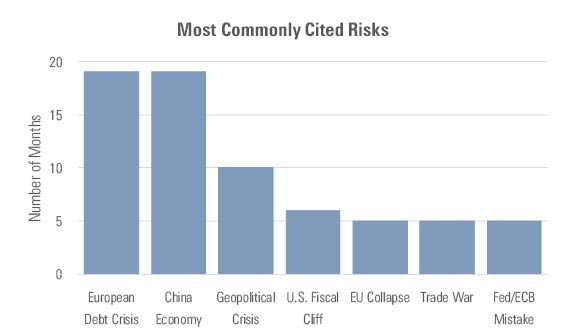

Tail Risks Each month, Merrill surveys 200 institutional investment managers across the world on various items. Among the questions asked by the BofA Merrill Lynch Fund Manager Survey is to state the biggest current "tail risk": the item that is likeliest to have caused a global-market meltdown, should such an event occur. Somebody clever decided to collect the winning answers for the past seven years and present them in a chart.

Unfortunately, Merrill's graphic is an eye test. I have created a condensed version below. Each bar in the chart represents a different issue, and each number represents one month for which that issue was the most widely cited tail risk. Thus, the European debt crisis and fears about the Chinese economy were the most common concerns, with each winning the tail-risk contest 19 times.

(In addition to the seven items presented on the chart, there were several more than appeared less frequently. In total, the seven-year period contained 18 noteworthy tail risks.)

Many Cries, No Wolves The lesson is straightforward: Ultimately, none of these economic discussions mattered.

That statement doesn’t necessarily apply to professional managers, who often seek to profit from tactical trades. For example, fund managers who recognized early that the financial markets would be spooked by the possibility of a European Union collapse, and who positioned their portfolios accordingly, gained on their rivals. (Then again, for each professional who got the trade right, there is another who did not. Tactics are a zero-sum game.)

But for individual buyers, who generally do not adjust their holdings because of monthly breezes, the tail risks were immaterial. Investors who created strategic asset allocations in 2011, and who were content to do nothing more than rebalance periodically, fared just as well as those who spent several hours each week following the latest economic news. The extra work from monitoring the news delivered no extra returns. A wasted effort.

There are a couple of caveats to this, one being that the game is not over. The 2012 topics may have become passe, but the recent problems are not. The trade wars, after all, appear to be just beginning. In addition, the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank seem to have much fiscal tightening ahead of them. It is premature to call these newer fears overblown. They may well end up sinking the financial markets, making this section appear foolish.

However, without the benefit of hindsight, how do we know that today’s apparition is the real thing, when so many false visions have preceded them? Month after month, year after year, economists and the financial media have seen wolves on the horizon. Month after month, year after year, the wolves have not materialized. Someday, to be sure, one of them will. But I know not why this might be the day.

Good to Know? The other admonition is that Merrill is, after all, surveying for "tail risks"--meaning that they are highly unlikely events. We should therefore not be surprised if none of these predicted possibilities have become real during the past seven years. The odds were always against such a thing happening. We should not expect economists to predict when the storm will arrive; it is enough that when it does arrive, the economists will have described what form that it will take.

That is a fair point, too. Once again, though, the question becomes how to use that information. It is all well and good if the most-skilled economists determine that the windstorm lies to the left rather than to the right. But there do not seem to be practical benefits to this knowledge. One cannot walk sideways indefinitely. The time lost by sidestepping during the normal conditions will be greater than the time gained by better withstanding the storm when it finally does arrive.

In summary, I do not see how individual investors (including your author) can profit from economic analysis. Strategic asset allocation doesn’t sound terribly appealing: "Close your eyes and keep doing the same thing." But as Winston Churchill said of democracy, strategic allocation is the worst form of investing, except for all the others.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/F2S5UYTO5JG4FOO3S7LPAAIGO4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/7TFN7NDQ5ZHI3PCISRCSC75K5U.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/QFQHXAHS7NCLFPIIBXZZZWXMXA.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)