A Tax-Smart Way to Give to Charity

The new tax law makes qualified charitable contributions from IRAs more appealing for many retirees. Contributor Mark Miller explains why.

Giving away money from your IRA is looking like a better bet than ever.

Well, perhaps not just giving it away, but donating to a charitable cause. The qualified charitable distribution permits IRA account owners of a certain age to use IRAs to make direct charitable contributions up to $100,000 annually. If you are charitably minded and older than 70 1/2, QCDs offer a tax-sensible route to giving after last year's Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

QCDs have always been interesting options for retirees who do not need to use required minimum distributions from an IRA to meet living expenses. But the QCD was available only on an on-again, off-again basis until Congress made it permanent in 2015. That really opened the door for using the QCD as a planning and tax efficiency tool.

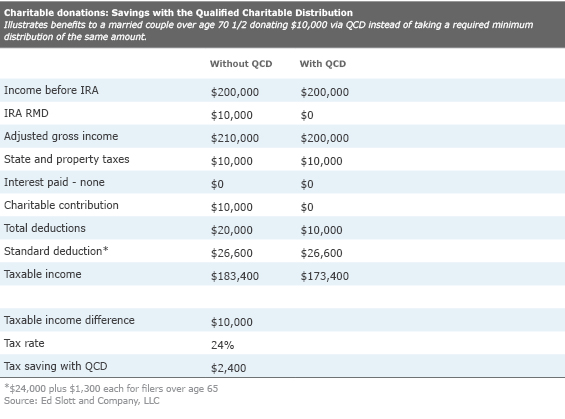

The new law raises the standard deduction to a level where fewer taxpayers will be itemizing deductions, including charitable contributions. The new standard deduction is $12,000 for single filers and $24,000 for married couples. But the standard deduction actually is higher for anyone considering a QCD, because taxpayers older than 65 can deduct an additional $1,300. That makes the standard deduction $13,300 for a single filer and $26,600 for joint filers.

All in all, many more people will be taking the standard deduction, effectively making charitable contributions using post-tax dollars more expensive, notes Ed Slott, an author and retirement expert who is one of the nation's leading authorities on individual retirement accounts.

That's not to say making donations from an IRA is the right move for everyone.

"It can make sense if this is money you were planning to give away anyway, and you are sure that you won't need it in the future," says Judith Ward, a senior financial planner with T. Rowe Price. "But think twice about it if this is money you might need down the road, especially for an emergency healthcare or long-term care need," she adds. "Sometimes we see clients who want to lower their taxes any way that they can without thinking about the longer-term consequences. You don't want to let the tax tail wag the investment dog."

Still, T. Rowe Price has seen an uptick in usage of QCDs since the 2015 changes, says Ward.

"We are expecting that to continue under the new tax law," she says.

Since passage of the tax law, the company has streamlined the paperwork required to make QCDs, allowing account owners to list all donations and amounts that they want to make on a single form.

Likewise, at Fidelity Investments, forms submitted for QCDs are up 103% through the first 27 weeks of this year, compared with the same period in 2017, a spokeswoman reports.

QCDs are excluded from taxable income, which means this amount effectively is added to your $26,600 standard deduction.

"Excluding something is the same as deducting," Slott notes. The QCD also counts as part of any required minimum distributions that you must take starting at age 70 1/2.

For a QCD to count toward an annual RMD, the funds must be distributed by your RMD deadline, usually Dec. 31. The funds must be donated to a 501(c)(3) organization eligible to receive tax-deductible contributions. QCDs can be made only from an IRA, not from your workplace retirement plan. QCDs cannot be made to private foundations or to donor-advised funds. (See below for more details on how QCDs differ from donor-advised funds).

When doing your taxes, make sure your tax preparer knows about the QCD: The IRS form you will receive is a normal 1099-R distribution form--it does not specify that the distribution was a QCD.

Slott offers the accompanying example of the QCD's benefits.

A married couple with income of $200,000 and an IRA RMD of $10,000 reduces taxable income by $10,000 using the QCD; in their 24% tax bracket, this translates to a tax saving of $2,400.

That saving is tacked onto the standard deduction.

"Excluding that $10,000 from adjusted gross income is the same as a deduction," says Slott, a certified public accountant. "You're getting the standard deduction plus this amount."

In some situations, a QCD can help minimize or avoid taxation of Social Security benefits, or Medicare high income premium surcharges. Slott doesn't include those savings in his high-income married couple example, noting that Social Security taxes kick in well below the income level for our hypothetical couple. And, the Medicare Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount is determined using a two-year look-back; surcharges paid in 2019 would be determined by your 2017 tax return.

QCDs versus Donor-Advised Funds Don't confuse QCDs with donor-advised funds, which are accounts created specifically for charitable giving. Donor-advised funds can accept contributions of cash, stocks, or assets such as real estate or a business. The donations qualify for a tax deduction in the year that you contribute, and the funds can be distributed to eligible charities over a longer period of time.

Donor-advised funds can be used at any age. But Slott notes that for donors older than 70 1/2, the QCD offers superior tax benefits because it reduces adjusted gross income; the donor-advised funds only reduces taxable income.

"Even if the DAF qualifies you for an itemized deduction, you would still do better with the QCD by reducing AGI," he says.

Morningstar columnist Mark Miller is a nationally recognized expert on trends in retirement and aging. He also contributes to Reuters, WealthManagement.com, and The New York Times. His book, Jolt: Stories of Trauma and Transformation, was published in February by Post Hill Press. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)