Easing the Retirement Crisis

Our research analyzes the practical actions that individuals and advisors can take to improve the retirement planning picture.

If you're currently working, how do you feel about your path to a comfortable retirement? If you have retired, I hope you're able to enjoy the fruits of your labor, as planned. For many Americans, unfortunately, their retirement simply isn't on track. As a range of studies have shown, nearly half of Americans have nothing saved for retirement, and for those who have saved, most balances are woefully insufficient even if Social Security is fully funded. In a recent EBRI survey, for example, only 17% of American workers felt very confident in their ability to retire comfortably (EBRI 2018).

This week, Morningstar released a new research paper, Easing the Retirement Crisis, in which I analyze the practical actions that individuals and advisors can take to improve this picture. I look at eight levers one could pull: from common topics in investing (increasing net returns, using a more aggressive asset allocation) to issues of financial planning (delaying retirement, adjusting one's standard of living in retirement, allocating more of one's funds to retirement, increasing contribution rates) to behavioral factors (auto-escalation over time, emotional reactions that forestall investing).

What We Studied For this study, we ran over 400 million simulations, based on a nationally representative sample of real Americans and their finances, to analyze the effectiveness of these actions on people's retirement readiness. The result is an unusually detailed look at how Americans are doing, and most importantly, what would help people succeed.

In this paper, we started with intentionally optimistic assumptions about retirement savings--fully funded Social Security, no periods of unemployment before retirement, and so forth--in order to determine if a gap still exists despite these assumptions (it does), and to focus on practical solutions individuals and their advisors can use to close the gap. Even with our optimistic assumptions, the vast majority of Americans (74%), including the majority of mass affluent households (55%), aren't on track to have what they need.

However, we found that the basic techniques--saving more, choosing to invest one's savings, delaying retirement, and lowering one's expectation of living--can be highly effective at increasing the likelihood of success for the majority of Americans. Surprisingly, this is true for mass affluent households as well. In the extreme, these techniques are far more impactful than other fine-tuned levers such as achieving alpha or adjusting asset allocations. What's right for a given individual will vary widely, of course, but across the population of mass affluent and other households the "big guns" are clear. When it comes to improving retirement readiness, thoughtful planning (when to retire and what to expect in retirement), and behavioral tools (increasing contribution, ensuring people invest at all) should be utilized first.

Austerity Can Be Avoided Taken individually, the actions most Americans would need to take are quite extreme. For example, by lowering their standard of living in retirement to 40% of their pre-retirement salary (including Social Security) or by contributing 20% more of their income from now until retirement, approximately 75% of households would be on track (up from 26%). These actions are powerful, but not simply not palatable.

Taken together, however, such extreme changes and severe austerity aren't needed. When individuals exercise these techniques at the same time, they multiply their effect. For example, we found that two combined changes, increasing contributions to a minimum of 6% and delaying retirement to a minimum of age 67 would have nearly the same effect as a 10-year delay in retirement, allowing more than 70% of households to have what they need for retirement.

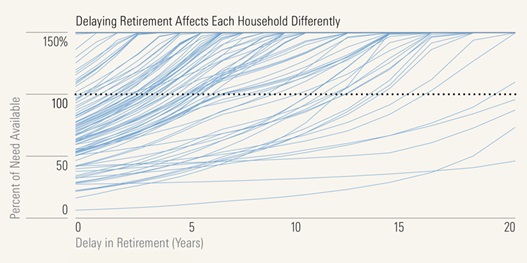

The Power of Personalization Each household, however, has its own personal and financial situation. What works for one family may not be particularly effective for another. For example, the following graph shows 100 randomly selected, real mass-affluent households from the Survey of Consumer Finances. It displays how delaying retirement affects how much money households will have available in retirement. As you can see, there is a broad range, even in this random sample: delaying retirement has a widely different effect, depending on where a given household is starting.

In another example, in one of the common areas in which defaults are given--401k contribution rates--nonpersonalized advice is particularly limiting and ineffective. We found that a single contribution rate fit the needs of only 9% of American households; everyone else is underserved by the default. In other words, the right answer isn't a new default: it's a personalized analysis based on what each household needs. Which, of course, is an area in which savvy individual investors and professional financial advisors and planners excel.

The Debate Over 'the Crisis": A Note About Methodology There are a range of estimates out there on the retirement savings crisis, and, at times, a shrill debate over it. To better understand this study, and the debate, it can be useful to look at why the debate occurs at all. It comes down to important differences of approach and what the studies are used for. Here are some of those differences.

- First, some studies are used to examine current retirees, and others look at future retirees. This study looks at future retirees, where the picture is more concerning.

- Second, there's a big difference in how death is handled: if a person doesn't have enough money for retirement, but happens to die soon after retiring, some studies count that person as not having been ready, and others say there was no shortfall. This study uses the first approach, since we focus on providing practical advice. One can't effectively predict whether a particular person is going to die at 65, so it's wisest to save and plan for a normal lifespan.

- Third, studies vary in how they project expenses and income in retirement. As noted above, we use optimistic assumptions to see if a gap exists even under those assumptions (yes, it does). Others provide detailed and pessimistic modeling of Social Security and pensions, health expenses in retirement, and such. Those projections are generally more negative than ours.

The Bottom Line Our new study, like many before it, shows that the vast majority of Americans are rightfully concerned about their retirement future. But, it does't have to be that way. By embracing a broad set of tools--especially financial planning and behavioral tools--and engaging in a personalized, individual analysis of one's particular needs, both individuals and the financial services industry can help Americans secure their financial future.

This paper and Morningstar.com article are part of the Investor Success Project. Learn more about the Morningstar Investor Success Project and read our latest insights.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/cc15194e-3c37-4548-9ca8-782ff113938c.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BZ4OD6RTORCJHCWPWXAQWZ7RQE.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/cc15194e-3c37-4548-9ca8-782ff113938c.jpg)