Reduce Taxes With Strategic Asset Location

Strategic asset allocation across tax-sheltered and taxable accounts can help reduce taxes.

A version of this report was published in the March 2018 issue of ETFInvestor.

Taxes are no fun. They may be an inevitable part of life, but savvy investment planning can reduce their impact. This type of planning requires holistic thinking about all your assets, considering asset allocation not only across asset classes and investment strategies but also across investment accounts. Tax-sheltered accounts, like 401(k)s, IRAs, and health savings accounts, are a good place to park less tax-efficient investments, like taxable-bond, dividend, and actively managed funds. Taxable accounts should be reserved for more-tax-efficient strategies, including low-turnover equity index funds.

This is a simple idea, but one that is often overlooked in practice. Too often investors fall into the trap of focusing on each individual account, trying to diversify locally, while losing site of the bigger picture. It's OK if a taxable account is a bit equity-heavy if it's offset by a larger bond allocation in a tax-sheltered account and you can tolerate the added risk in the taxable account.

It is important to balance risk tolerance against the tax advantages of using different accounts to hold different types of assets because the money in tax-sheltered accounts may not be as easily accessible as money in a taxable account. If you need the money in the taxable account sooner, make sure that it is invested in a manner consistent with your risk tolerance over that horizon.

With that caveat, here's a closer look at why taxable bonds, dividend strategies, and most actively managed mutual funds tend to be better suited for tax-sheltered accounts.

For Tax-Sheltered Accounts With the exception of funds that invest in municipal bonds, which are exempt from federal taxes, most bond funds (both active and passive) are not very tax-efficient because they generate a large portion of their returns from regular interest (coupon) payments. These payments are taxed at ordinary rates, which for most are higher than the tax rates on long-term capital gains and dividends, and investors cannot defer them. Even funds that target lower-coupon bonds can be tax-inefficient because they have to constantly replace holdings as they approach maturity, leading to high turnover and potential taxable capital gains distributions.

Dividend funds' tax inefficiencies generally aren't as egregious as bond funds' because dividend distributions are usually taxed at lower rates than interest payments. Qualified dividend payments are taxed at 15% for most investors (though the rate for top earners is 20%, plus an additional 3.8% tax on net investment income). On top of those federal tax rates, investors must pay state taxes (if applicable) on dividend income.

Although most dividends are taxed at more favorable rates than interest income, dividend income funds tend to be less tax-efficient than their lower-yielding counterparts. This is because investors must pay taxes on dividends when they are received and don't have the option to defer them as they do with unrealized capital gains. There is value in deferring tax payments: Such deferrals allow money that would have been taxed to continue to grow, leading to higher aftertax returns when the investment is finally sold. So, it's more tax-efficient to generate returns from capital gains that can be deferred than from dividend payments that cannot.

Of course, capital gains are no more tax-efficient than dividends if they are not deferred. Most actively managed mutual funds regularly distribute capital gains during bull markets, which hurts their tax efficiency. These capital gains distributions are triggered anytime a manager sells securities for a gain and does not have enough losses elsewhere to offset them, even when investors haven't sold any shares in the fund. Most managers don't think about the tax implications of their trades because they are being assessed on pretax performance. That said, there are some good tax-managed funds that focus on aftertax returns.

While all mutual funds must distribute all of their capital gains each year, actively managed funds tend to be less tax-efficient than their index counterparts because they tend to have higher turnover. This leads to more sales in the portfolio and a greater chance of realizing capital gains. Like turnover, greater outflows can lead to higher capital gains distributions and larger tax bills, as they often require managers to sell some of their holdings to raise cash.

Tax-sheltered accounts effectively allow investors to avoid the tax drag that plagues these investments. For example, traditional IRA and 401(k) accounts allow investors to deduct contributions from their taxable income and defer the tax liabilities from the contributions and investment returns until funds are withdrawn from the account, allowing investments to grow tax-free.

For Taxable Accounts Investment tax planning should not stop with tax-sheltered accounts. You can further reduce tax liabilities by placing more-tax-efficient investments in taxable accounts. These include equity index funds, particularly exchange-traded funds and funds that invest in foreign stocks, and municipal-bond funds.

Broad, market-cap-weighted equity index funds are generally tax-efficient--even in a mutual fund wrapper--because they have low turnover. ETFs build on this tax advantage by externalizing much of the trading to the secondary market and allowing the portfolio managers to move low-cost-basis shares out of the portfolio through a tax-free, in-kind redemption with their authorized participants (who are the only ones that can directly take money out of the fund).

When authorized participants take money out of an ETF, they send their shares of the ETF to the fund company and receive shares in the fund's holdings in return. This is a nontaxable transaction, and it gives ETFs a big advantage over mutual funds, which often have to sell their securities to raise cash to meet redemptions. This in-kind redemption mechanism may not completely eliminate capital gains distributions, but it makes them less likely.

Index funds that invest in foreign stocks are especially well-suited for taxable accounts because investors can receive a tax credit for foreign withholding taxes on dividends, but only if they are held in a taxable account. If you hold these funds in a tax-sheltered account, the fund still pays the foreign withholding taxes on dividend income, but you can't recoup them.

The foreign withholding tax credit can make a difference. During the trailing 10 years through April 2018, the gross return version of the MSCI All Country World Index beat the net return version, which reflects the impact of foreign withholding taxes on dividends, by 57 basis points annualized. The foreign tax credit would have allowed investors to recover a good chunk of that return spread.

While equity holdings tend to be more tax-efficient than bonds, it isn't necessary for taxable accounts to be composed solely of equity holdings. Municipal-bond funds are among the most tax-efficient investments available because their interest payments are exempt from federal taxes (and state taxes if the owner resides in the state of the issuer). Because of their favorable tax status, municipal bonds tend to offer lower yields than their taxable counterparts. But for investors in the highest tax brackets, municipal bonds generally offer better aftertax yields than taxable bonds with similar risk.

Rectifying Past Mistakes What if you already have an actively managed fund (or other tax-inefficient holding) in your taxable account? Is it better to hold on to that fund and defer taxes on the unrealized gains, or sell it and replace it with a more tax-efficient and lower-cost ETF?

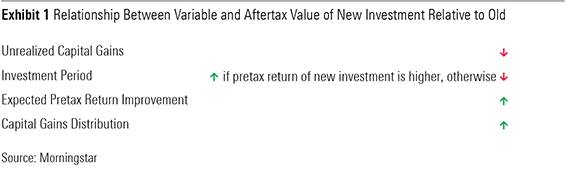

The answer depends on several key variables: unrealized capital gains in the initial investment, investment period, tax rate, expected returns of the two investments, and expected capital gains distributions. Exhibit 1 summarizes the relationship between each of these variables and the relative aftertax value of replacing an old investment with a new one.

While there are a lot of variables in play, a modest improvement in expected pretax returns over a long investment horizon can justify making the switch. The math is complicated, but to illustrate, I created some hypothetical examples.

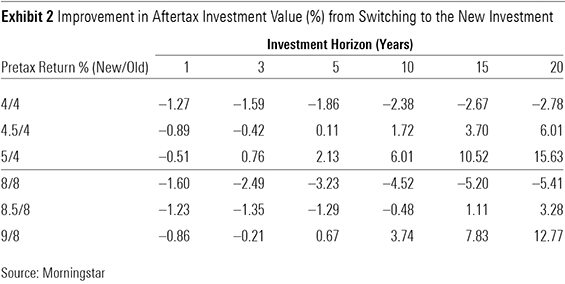

These examples assume a 50% unrealized capital gain on the original investment, a 20% tax rate (which reflects the 15% long-term capital gains rate that most investors face, plus an additional 5% for state taxes), and that the original investment distributes 25% of its annual return (while the new investment makes no distributions). I tested these parameters under several expected return and investment horizon assumptions.

These scenarios compare the aftertax value of the new investment with the original investment. In calculating the aftertax value of the new investment, I assume that the investor sells the original investment, pays the taxes on the unrealized capital gains, places the aftertax proceeds in the new investment, and sells the new investment at the end of the investment horizon, paying all applicable taxes. The results are shown in Exhibit 2.

This data demonstrates that if there is no difference in the pretax return of the two investments, it is better to continue to hold the original investment, despite its annual capital gains distributions. The higher aftertax value of the original investment comes from the value of deferring the unrealized capital gains taxes that an investor would incur in switching between the two investments.

However, a small improvement in expected pretax returns over a long investment horizon can justify the switch. The magnitude of the return advantage required increases with the returns of the two investments. For example, when the original investment was priced to offer a 4% pretax return, the new investment would need to offer only a 50-basis-point return advantage across five years to come out ahead after taxes. But if the original investment were priced to offer an 8% pretax return, it would take an 83-basis-point pretax return advantage to break even after taxes.

Cost savings from lower fees can often provide this type of pretax return improvement. So, if you can realize 1 percentage point worth of annual cost savings by switching from an actively managed mutual fund to an ETF, it could be worth doing so, even with the tax hit from recognizing the unrealized capital gain.

Putting It All Together

- Most bond, dividend, and actively managed equity strategies are best suited for tax-sheltered accounts, including 401(k)s, IRAs, and HSAs.

- Municipal-bond and equity index funds, particularly ETFs and international-equity funds, are well-suited for taxable accounts.

- If you have a tax-inefficient holding in your taxable account with a sizable unrealized capital gain, don't switch into a more tax-efficient investment unless it offers a higher expected pretax return and you have a long investment horizon.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/24UPFK5OBNANLM2B55TIWIK2S4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)