The More Stocks, the Merrier

On average, broadly diversified funds have outperformed concentrated funds.

Testing the Assumption Tuesday's column off-handedly stated that, as a group, concentrated stock funds—those funds with relatively few holdings—don't outperform funds that have large portfolios. That comment could stand some testing. It certainly held true in the past, when I researched the subject, but perhaps things have changed. Also, if concentrated funds do prove to be no better than other types of funds, are they similar in quality? Or outright worse?

I began by defining the term: Concentrated funds are those with 50 equity positions or less; those funds with more holdings are not. It was a false start. Treating the topic as binary, so that all funds land into one of two categories, would be needlessly restrictive.

Then, I arrived at another realization. Rather than frame this study as being about the effects of concentration, I should consider the issue more broadly, by also examining how portfolios behave as they grow their holdings. It could be that the most significant results come not when funds hold few securities, but rather when they own many. Good thinking, Rekenthaler. Not completely and fully good—but I will save that tale for last.

The study started with diversified U.S. equity funds (oldest share class only), while removing index funds. Investigating whether portfolio size affects indexing strategies is a worthwhile topic, but it is a different affair than studying the results of active management. Best not to combine the two. Finally, I eliminated funds that were less than five years old.

(One final step: jettisoning DFA funds. Although DFA regards itself as an active manager, in that it exercises some judgment on what stocks to place into its funds, and more judgment yet on the timing of its trades, its funds look and behave much like index funds. They are used that way as well—typically as alternatives for conventional market-cap index funds. Sorry about that, DFA.)

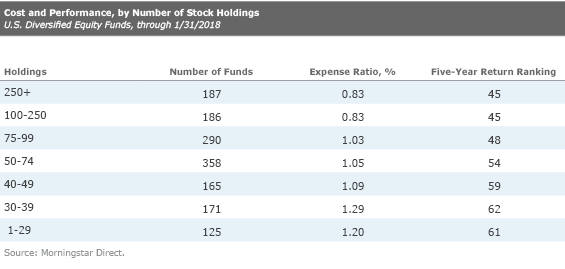

The Sign of Seven The remaining 1482 funds were placed into seven portfolio-size buckets:

1) 250 holdings or more 2) 100-249 3) 75-99 4) 50-74 5) 40-49 6) 30-39 7) 1-29

Arbitrary boundaries, to be sure, but they worked out well. All groups contain between 100 and 200 funds, except for the 50-74 and 75-99 sections, which are larger. That is acceptable; there is little, if anything, to be learned by differentiating between those funds with 80 positions and those with 90.

I calculated group averages for three items: 1) expenses, 2) returns, and 3) volatility. Somewhat surprisingly, at least to me, the volatility numbers were almost identical, from top to bottom. However, the first two figures showed clear patterns. They are charted below. (I dispensed with volatility, since those numbers signified nothing.) Expense ratios are from the most recently reported year, while the five-year return scores are Morningstar Category rankings. As with golf scores, lower category rankings are better. One is the best and 100 the worst.

Bigger Was Better There wasn't a lick of difference between the two highest groups. Whether a fund had 100 holdings or 1000 appeared to be immaterial. From that point downward, the arrangement was monotonic, as a true scientist might say, until the final group's uptick. The smaller the portfolio size, the pricier the average fund in that group, and the worse its average five-year performance. To put the matter more positively: The more holdings, the merrier.

Not quite what I expected. I knew that funds with fewer holdings would be somewhat more expensive—ironic, if you think about it—and was pretty sure, as related earlier, than concentrated funds wouldn’t be the outright winners. However, I did not anticipate that the performance gap between the highest-returning group and the lowest-returning would be so large. Seventeen percentage points, the distance that separates the 45th percentile average for the two top buckets and the 62nd average for the 30-39 buckets, is substantial.

The immediate temptation is to credit (or blame) that difference on expenses. Annual costs for the 30-39 group run almost half a percentage point higher than those of top buckets. Roughly speaking, however, that 17-point disparity in the performance rankings equals 1 percentage point in annual return. Thus, while half owes to costs, the other half comes from somewhere else.

Some of that half that can be attributed to a subtle style effect. The funds that have the most holdings tend to have more assets than the more-concentrated funds, which in turn means that they buy larger companies (at least for their top positions). They therefore benefited from the time period, because over those five years large-company indexes outgained smaller-company indexes. The effect is modest, because separating the funds into investment categories and using category rankings, as I did with this study, mostly eliminates it. But not entirely.

However the math plays out, the conclusion is inescapable: Once again, concentrated funds did not make a case for themselves. Of course, as Morningstar’s research analysts never tire of telling me, “You have only looked at averages! Just because an average is lower doesn’t mean that there aren’t opportunities.” Perhaps one cluster of funds is truly awful, another is very good, and the truly awful overwhelms the very good when the average is calculated.

That is true. My next task is to dive into the weeds and see if there are any clusters to be found. Next column, I will report on what I find—or perhaps the column after that, if that review takes a while.

Brain Freeze At this point, you might say: "How about beginning with the 1-29 bucket? It is the sole exception to the overall rule of the fewer the holdings, the costlier the funds, and the lower their returns. That might contain some gems."

Now my fault will be admitted. When I removed index funds, I neglected to remove “enhanced-index funds”—an odd breed that sometimes operates by buying stock-index futures, while keeping the bulk of fund assets in cash and/or short-term bonds. They, correctly, are classified as stock funds, because that is how they behave. But because they purchase futures, not individual stocks, they register in Morningstar’s database as having very few holdings.

Thus, the bright spot for the highly concentrated group consists of … index funds. Irony indeed! And a lesson to your author about taking that final step, when conducting screens.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WC6XJYN7KNGWJIOWVJWDVLDZPY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HHSXAQ5U2RBI5FNOQTRU44ENHM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/737HCNGRFLOAN3I7RKGB7VPEKQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)