Putting Larry Fink's Corporate-Governance Comments to the Test

Two counterarguments, as well as some numbers.

Not So Fast BlackRock CEO Larry Fink's contention (discussed in Wednesday's column) that corporate managements should attempt more than maximizing "shareholder value" was not universally acclaimed. Many people like the American system just as it is, thanks much.

One accusation was that Fink made a bull-market argument. It is easy to talk about how there is more to life than profits when the table legs are buckling from the weight of the feast. It is not so easy if the cupboard is bare.

Wrote Joe Cahill, "Big-time investors and globe-trotting chief executives gladly extol social values when profits are surging and stock markets are hitting all-time highs. When earnings shrink and share prices descend, expect them to recall what [Milton] Friedman said about a company's one and only social responsibility."

Hmmm. Revolutions generally arise from failure, not success. For example, the primacy of shareholder value arose from its own set of ashes. From 1966 through 1982, the S&P 500 made no real gains; its after-inflation return for that 14-year period was zero. By the mid-1980s, shareholders were ready for change. Bring on shareholder value; make CEOs accountable for nothing but those long-awaited stock-market profits.

Also, the 1990s "New Era" bull market was as long and strong as today's, yet it did not lead to extensive corporate-governance discussions. What has changed is the ascendance of indexing. Passive investors hold their companies forever. Naturally, they have a different perspective on corporate governance than will active managers, who can vote with their feet by selling shares. That seems to me the driver of Fink's comments, not the length of the current bull market.

Barnum and Fink A harsher attack on Fink came from The Wall Street Journal's "Stocks Aren't Made for Social Climbing," penned by hedge fund manager Andy Kessler. Hedge fund managers are not known for understatement, and Kessler proved no exception. "P.T. Barnum supposedly said there is a sucker born every minute," he scoffed. "The basic idea [of Fink's proposal] is to throw money away."

Not so, Mr. Kessler. The idea of Fink's proposal is for companies to make more money. The logic is that by considering a broader set of objectives than (say) raising their stock price for the next three years, corporations will aid the economy. That would increase long-term demand for their products and services, and thus bolster their stock prices. The rationale is, ironically, a cousin of the trickle-down theory that Kessler surely embraces: If you want to float all boats, then do your best to raise the tide.

This disagreement cannot be resolved theoretically. Implicitly, Kessler's argument assumes that Adam Smith's "invisible hand," which leads to optimal results when a group of people make rational, self-interested decisions, is an absolute rule. But the invisible hand is just a general precept: Many times it holds, but sometimes it does not. In writing his article, Kessler presumes too much. He states as a fact that which he needs to demonstrate.

Then again, so does Fink. He contends that conditions have changed; that government policies are no longer sufficient to address key social needs; that corporations need to fill the gaps; and that in doing so, companies will end up being more profitable, with higher stock prices, than they would be if they continue their current practices. All assertions requiring support that is not given.

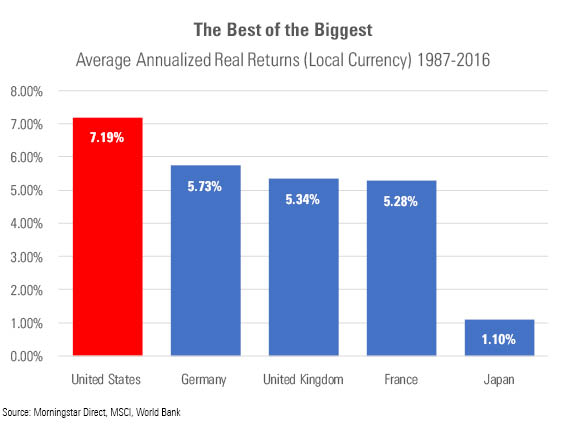

The Numbers This discussion on corporate governance is thus a political debate and lies outside the scope of this column. We can, however, take a cursory look at the investment evidence. I have assembled the after-inflation returns for several stock markets for the 30-year period of 1987-2016. (The performances were calculated in local currencies.) In distinguishing itself by being the strongest practitioner of the doctrine of shareholder value, did the United States achieve higher stock returns?

-

Against the largest markets, yes it did. When compared against Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Japan (poor Japan), the U.S. was easily the best. Of course, that does not necessarily reflect victory for the American approach to corporate governance. The margin was largely driven by technology stocks, which quite reasonably could be credited to the excellence of U.S. research universities and/or the availability of venture capital … but nevertheless, a win is a win. One point to Kessler.

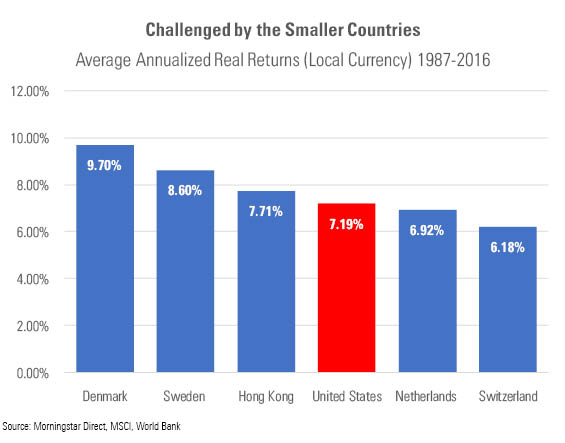

However, when compared with the mid-major countries, the U.S. doesn't appear so exceptional. The Nordic markets of Denmark and Sweden comfortably outgained the U.S. during the three-decade time period, and Hong Kong was ahead as well. The Netherlands was close behind. In short: Some countries that have corporate-governance policies similar to what Fink proposes have profited handsomely.

-

Again, objections can be raised. These markets are much smaller than that of the U.S., and their demographics are more homogenous. That makes the comparisons not even that of apples and oranges; rather, they are cherries and grapefruit. Fair enough. At the same time, the numbers permit Fink to even the score. Kessler can't end the debate by invoking Adam Smith; not only are there theoretical arguments against regarding the invisible hand as an inviolable rule, but there is also some actual counterevidence.

In short, Fink has advanced an argument that might be correct. It cannot be dismissed out of hand as being theoretically wrong, nor can it be squashed with the preliminary evidence. What's more, BlackRock is so huge that even if it gathers no followers, it will have some ability to change corporate governance. But if it wishes to convince the majority, particularly among active managers, it has much work ahead of it.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CFV2L6HSW5DHTFGCNEH2GCH42U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/7JIRPH5AMVETLBZDLUSERZ2FRA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YWKBIVULT5DGJEIGAJGBA6H5ZA.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)