How to Allocate Assets for College Savings

Families must contend with competing challenges: time and high inflation.

A version of this article was originally published on Jan. 25, 2021.

Finding the right asset allocation--or mix of investments--for college can be a tricky business. If you're a minimalist, it may be tempting to buy a good-quality balanced fund and call it a day. Especially if you're just starting out and the assets in the college savings plan are still small, it may seem like overkill to manage a college portfolio with lots of moving parts.

There are certainly worse ways to go about saving for college (life insurance, anyone?). But before you invest your college savings in anything, it's worth considering how investing for college is different from saving for that other long-term goal--retirement. Those differences, in turn, argue for taking a more hands-on approach to asset allocation than a balanced fund would allow. Nor do target-retirement vehicles fit as one-stop options for college savers.

Truncated Time Horizon

In contrast to retirement, your child's college matriculation year isn't a negotiable date. A person who encounters a bear market shortly before retirement may have some wiggle room to keep working or rely on other sources of income to avoid tapping his nest egg at a low ebb. But try telling your 18-year-old that he'll have to wait until age 21 to start school so that his college fund will have time to recover.

In addition, your time horizon for saving for college is much shorter than is the case for retirement, as is the time horizon for spending those assets. One might save for retirement for 40 years or more and be retired for another 30 or 35 years. But you have less than half that amount of time to amass the funds needed for college, and if all goes well, you'll spend down those assets quickly--in four years or so, or perhaps a few more if you're also footing the bill for graduate school.

Both of those facts call for a much steeper glide path--the gradual shift from more-volatile investments such as stocks to more-conservative investments such as bonds--in the years leading up to and during college than the typical glide path before and during retirement.

A college portfolio's asset allocation should begin downshifting into cash and bonds when the child is in grade school, and the portfolio should be dominated by bonds by the time the child is in high school. That's because an equity-heavy college fund that encounters a bear market in the years leading up to college could incur losses that it couldn't recoup during the student's time horizon. Even parents who worry that they're grievously behind on college savings should resist the urge to swing for the fences by maintaining a too-high equity allocation too long. (That may be a great temptation for college savers right now, as stocks have trumped bonds and cash over the past decade.)

Inflation a Bigger Foe

Yet college savers must strike a tricky balance because the risks of being too conservative also loom large. Inflation is a major foe for college savers, and a portfolio heavy in bonds and cash could have trouble keeping up with rising tuition costs.

While college costs have come under some pressure very recently, the college inflation rate has been double the rate of general inflation since 2001. But current yields have historically been a good predictor of future bond returns, and the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index, which serves as a broad bond market benchmark, is currently yielding about 1.7%. That means that investors with extremely conservative asset-allocation plans are going to have difficulty matching the rate of college inflation.

Finding a Baseline

Given the specific considerations that should go into a college savings allocation plan, it's probably no wonder that the age-based options within 529 college savings plans have historically held the lion's share of assets. Age-based options aim to provide age-appropriate asset mixes that gradually become more conservative over time, and in so doing they take the onus off of parents and other family members to arrive at an optimal asset mix and to provide ongoing oversight of a portfolio of individual holdings.

But the age-based plans also vary widely in their glide paths, and plans are increasingly offering multiple options for a given age band: conservative, moderate, and aggressive. That makes it important to conduct due diligence on a prospective plan's asset-allocation framework and see how it compares with other options within that same general age band. If it's an outlier, make sure you understand and agree with the rationale that its managers use for diverging from the peer group.

After you select a plan from your (or any other) state from Morningstar's 529 Plan Center map you can see how that state's age-based glide path compares with the 529 averages for that same age band. For example, the Silver-rated Maryland Senator Edward J Kasemeyer College Investment Plan, managed by T. Rowe Price Group TROW, has a heavier equity weighting (green bar) than its peers (gray mountain chart), especially for younger children with several years until college.

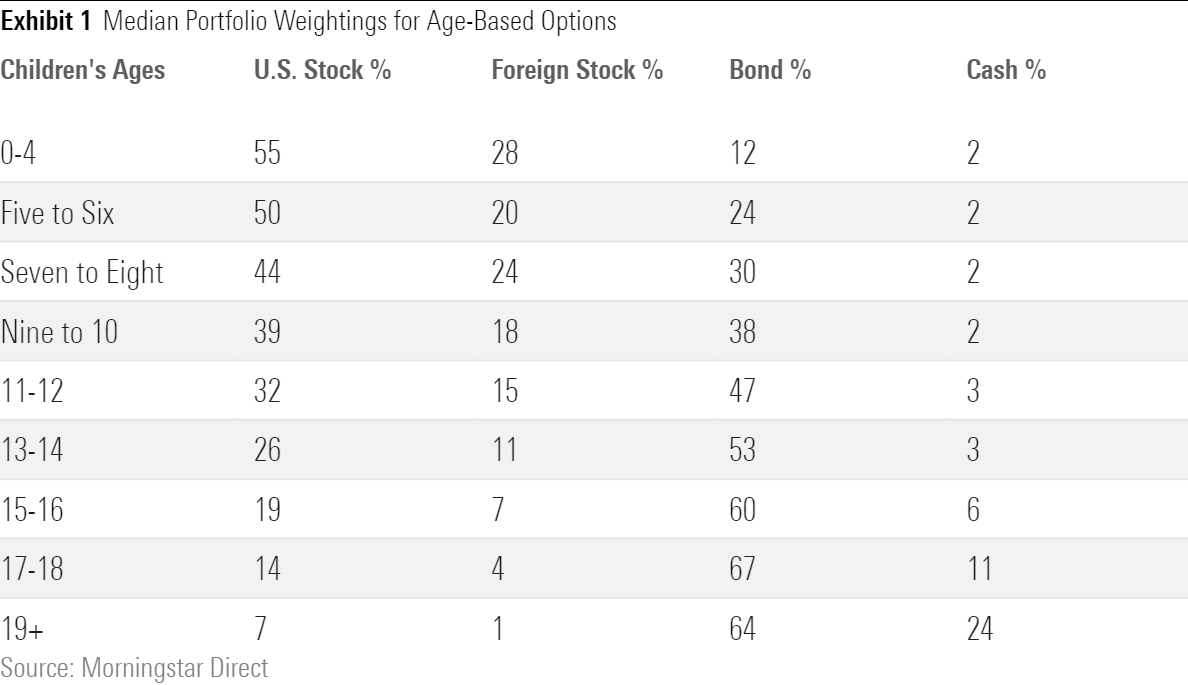

Even families who aren't using an age-based 529 option can still use 529 glide paths to help get their own plans' asset mixes in the right ballpark. In the table below are the median net equity, bond, and cash weightings for each of Morningstar's age-based 529 categories. You can see that the plans start out with the majority of their assets in equities, then gradually become more conservative over time.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/66112c3a-1edc-4f2a-ad8e-317f22d64dd3.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/66112c3a-1edc-4f2a-ad8e-317f22d64dd3.jpg)