Passive Firms Take Active Approach to Stewardship

Index funds are becoming more engaged with investee companies.

As assets continue to flow from actively managed to passively managed strategies, the largest index asset managers1 are becoming increasingly influential, often ranking among the largest investors of public companies. Despite this fact, little research has been done to understand how index managers carry out their investment stewardship responsibilities.

It is legitimate to assume that index managers have little incentive to allocate resources to monitor corporate governance of investee companies, because, after all, index managers tend to compete on fees, and their overriding objective is to match the performance of indexes. Our research shows, however, that the notion that these managers take a laissez-faire approach to governance could not be further from the truth.

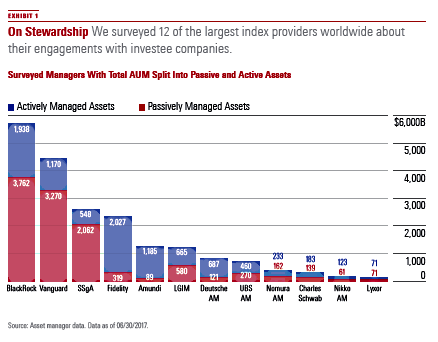

To better understand the stewardship activities of index managers, we surveyed 12 of the largest providers of index funds and exchange-traded funds across the United States, Europe, and Asia ( EXHIBIT 1 ). These include not only global asset managers such as BlackRock BLK and Vanguard, but also smaller firms that are key providers of passive funds in their local markets, such as Charles Schwab SCHW and Lyxor. Collectively, the firms surveyed have more than $20 trillion of assets under management.

- source: Morningstar Analysts

Our research shows that the shift to passive investing hasn’t led to an abdication of stewardship responsibilities. Quite the contrary. Index managers are increasingly taking an active stance in the oversight of investee companies. They are more committed than ever to using the tools at their disposal, chiefly voting and engagement, to improve the environmental, social and governance, or ESG, practices of companies.

Large asset owners have led the push for increased oversight, as more and more believe that ESG integration and active ownership practices— through voting and engagement—can have a positive impact on investment performance. Regulators have contributed further with the adoption of stewardship codes in several countries, including the U.K., Switzerland, and Japan.

Another factor fueling the change in behavior among index managers is the tremendous growth of the assets they manage. Assets in traditional index funds and ETFs have grown fourfold since the financial crisis and now account for close to one fourth of total fund assets globally, according to Morningstar data.

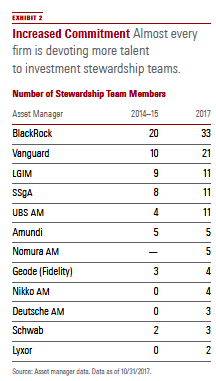

Perhaps the single most compelling piece of evidence of the increased commitment to active ownership practices among index managers is the growth of their investment stewardship teams. For example, BlackRock expanded its team from 20 members in 2014 to 33 today; Vanguard’s team went from 10 in 2015 to 21; and UBS UBS will employ 11 dedicated professionals to stewardship by the end of 2017, up from four in 2015 ( EXHIBIT 2 ). These increases will allow the firms to undertake more and better-quality engagements with investee companies.

- source: Morningstar Analysts

The role of index managers as active owners is all the more important in that they are the ultimate long-term shareholders of listed companies. Unlike active portfolio managers, index managers can’t sell poorly run companies. They must either put up with their bad governance practices or encourage positive change through voting and engagement.

That said, one shouldn’t assume that all index managers undertake stewardship activities in the same way. From the responses to our survey and our interactions with the firms, it is clear that voting and engagement activities vary significantly—not just according to the size and predominant investment style (passive or active), but also according to the philosophy, region, and history of the asset managers.

Below, we share our findings and highlight what managers have in common and areas where they differ.

Voting Behavior Is Changing We found that firms that offer both actively managed and index-tracking strategies apply their voting policies universally to all portfolios, irrespective of investment style. The only exception was Fidelity, which delegates the full management and voting responsibilities of its index funds to subadvisor Geode. Therefore, Geode's proxy voting policy and activities are completely separate from Fidelity's. In our view, this setup has the disadvantage of duplicating efforts and limiting the benefits of scale with respect to proxy voting.

Meanwhile, the scope of voting varies widely across asset managers, depending primarily on their size. Large managers with a global reach, such as BlackRock and Vanguard, typically vote for all portfolio holdings where possible as long as the potential benefit of voting outweighs the cost of exercising the right. By contrast, smaller firms and those with fewer resources, such as Deutsche Asset Management and Lyxor, focus more on their home country or region, or on their largest holdings. For example, Deutsche AM works with a “watchlist” of around 700 companies that typically represent around 50% of its equity fund assets under management.

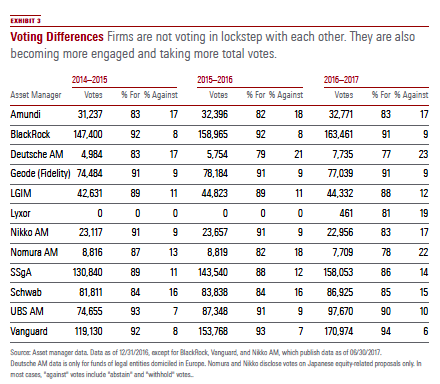

The starting position for all surveyed asset managers is to be supportive of company management and boards, as most votes are linked to routine administrative matters. However, as voting records show, there are significant differences among firms in how they voted, especially with respect to voting against management (EXHIBIT 3 ).

- source: Morningstar Analysts

We’re starting to see anecdotal evidence of mounting dissent. This is particularly so in the case of U.S. asset managers, who relative to their European counterparts, have been historically more reluctant to challenge the status quo, especially in relation to environmental and social issues.

One recent high-profile case was Exxon Mobil XOM. BlackRock and Vanguard supported a shareholder proposal seeking greater disclosure of climate-related risks, against the Exxon board’s recommendation. This was the first climate-risk disclosure resolution Vanguard had ever supported. Other asset managers, including SSgA, Amundi, and LGIM, had already voted in favor of the proposal in 2016.

SSgA also made headlines recently after its opposition to the re-election of directors at 400 companies for failing to appoint more female board members.

Meanwhile, in a sign that change is coming to Japanese corporate culture, Japanese asset managers are now also opposing company management more. For example, after the adoption of more stringent voting criteria in areas such as election of directors, the number of Nikko’s votes against management doubled in two years, reaching 17% in 2017.

Despite a general sense that asset managers may be increasingly open to using negative votes, key differences remain in the way these votes are deployed. For some, voting against management remains a last-resort option. For example, BlackRock will first try to effect change by engaging management teams and will only cast a negative vote if management is unresponsive or takes too long to address BlackRock’s concerns. At the other end of the spectrum, Europe’s largest asset manager, Amundi, has a strict voting policy and does not hesitate to swiftly vote against management when a proposed resolution fails to comply with its principles.

Another noteworthy difference among the surveyed firms lies in the varying level of authority that active portfolio managers have in voting decisions. For example, at BlackRock, Amundi, and UBS, the policy is for active fund managers to vote consistently across all funds, but they retain the authority to vote differently from the house view. This contrasts with the approach adopted at Vanguard, SSgA, and LGIM, where the corporate governance teams have ultimate authority on the final votes. This is to ensure consistency and efficacy, as well as to minimize potential conflicts of interest.

Index portfolio managers, meanwhile, have no say in the voting of their portfolio holdings. Index portfolio management is a highly automated process where delivering the index performance is the overriding mandate. That said, index portfolio managers can be consulted in some organizations for policy-level decisions and informed of certain votes.

Increased Commitment Toward Engagement Our research shows that index managers are also intensifying their efforts in the area of engagement. Of the 12 surveyed firms, nine reported that they undertake direct engagement activities with companies and expressed a willingness to increase their engagements in the future.

Of the three that do not engage, two, namely Fidelity's subadvisor, Geode, and Lyxor, have plans to formalize an engagement strategy in the coming months, in line with their commitment to the U.N. Principles for Responsible Investment.2 These principles require signatories to be "active owners" and incorporate ESG issues into their ownership policies. By contrast, Schwab was the only firm to see no compelling reason to set up an engagement program, citing cost and what it sees as a lack of solid evidence about the benefits of direct engagement.

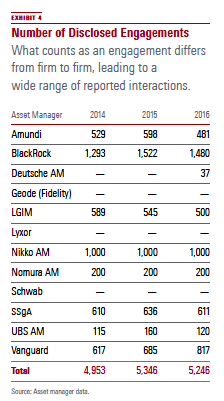

Despite the emphasis placed on engagement among nearly all of the surveyed firms, it is difficult to compare their activities. This is because there is no standard definition of what constitutes an engagement. For some, a fact-finding meeting or call with a company is enough to be recorded as an engagement; others apply a more stringent definition, only classifying as engagement meaningful interactions aimed at bringing about change through dialogue with companies. As a result, our research shows a wide range of numbers of engagements disclosed in 2016—from 37 by Deutsche AM and 120 by UBS to around 1,000 by Nikko and 1,480 by BlackRock ( EXHIBIT 4 ).

- source: Morningstar Analysts

However, irrespective of the definition, our data revealed an increase in the aggregate number of direct engagements, with BlackRock and Vanguard reporting the most significant growth. Some of the surveyed firms expect the quantity as well as the quality of their interactions to rise further in the years ahead. At the same time, most surveyed firms reported that companies are increasingly eager to reach out to them to exchange opinions on ESG issues.

We found that most surveyed firms that have a structured program of direct engagements seek the support of their investment teams. In fact, in some cases, especially in firms where active management dominates (for example, Amundi and UBS), the ESG analysts and portfolio managers primarily drive the engagement process.

When it comes to the issue of joining forces with other investors, including activist investors, the views are split. Given their size, the largest asset managers (such as BlackRock, Vanguard, and SSgA) have a clear preference for one-to- one engagements, ideally behind closed doors. Others, typically smaller firms, are keener to work with peers and share resources, especially in cases when individual engagements would have a low likelihood of success. All, however, are subject to regulatory constraints. In some countries, such as the United States and Germany, engagement is at risk of being seen as collusive practice.

Disclosure—An Area Needing Improvement Transparency of voting and engagement activities is an important part of an asset manager's stewardship duties. Yet the variety of national regulatory requirements and customs mean that disclosure practices differ significantly between managers and countries.

Most surveyed asset managers publish voting records for their funds on their websites in countries where the regulator or a stewardship code require them to. But too often these records are hard to find, and where disclosure isn’t a requirement, they may be inexistent. Also, very few explain the rationale behind important votes (that is, votes against management, abstentions, or contentious votes). This is certainly an area for improvement. Indeed, providing reasons behind a vote allows stakeholders to assess whether the asset manager has voted in line with its policy and in the best interest of shareholders.

Meanwhile, with respect to disclosure of engagements with investee companies, differences are even more pronounced. Some managers, including BlackRock, Vanguard, and UBS, are averse to disclosing the names of the companies with which they engage. They believe that to build trust and develop constructive long-term dialogues with company management and boards, conversations need to be kept confidential. Some commented that “naming and shaming” can be detrimental. This, however, doesn’t seem to be a concern for Amundi, which publishes an annual engagement report detailing nearly every action it had with companies during the year. SSgA also discloses the names of all the companies with which it engages each year, but it only provides full details on a selected number of successful engagements.

In the future, we expect increased disclosure of voting and engagement activities. Already, there is pressure on asset managers to share more details on voting decisions with the public. Equally, more companies will be publicly named and shamed when engagement has failed. It’s already been seen in high-profile cases such as Exxon Mobil. This year, BlackRock started publishing—on a very limited basis—statements on its engagements and votes in relation to certain proposals.

We also expect index managers to become more vocal on ESG topics through public statements on their websites, opinion pieces in major publications, speaking engagements, and interactions with the media. Ultimately, this will also influence their product offerings. In fact, it already has. The SPDR SSgA Gender Diversity ETF SHE provides a good example of a fund created to advance a manager’s cause.

The Issue of Cost Our study of index managers' stewardship practices would not be complete if we didn't address the issue of cost. The additional human and technological resources allocated to voting and engagement activities have come at a cost for all the surveyed managers. And as their ESG-dedicated teams continue expanding and developing their expertise, the expenditure will continue to rise. This raises the question of whether these firms will be able to absorb the extra cost without increasing their fees.

While large asset managers with economies of scale should be able to absorb the additional costs, it might be more of a challenge for the smaller firms. To remain competitive, these firms will have little choice but to either do the minimum required or go down the outsourcing route.

Expect Greater Scrutiny As assets continue to flow into passive strategies and responsible investing becomes increasingly important, one can only expect greater scrutiny of index managers' stewardship activities. As our research shows, the largest index managers in the world have intensified their efforts in the areas of voting and engagement. They are looking to influence investee companies and help improve ESG standards across the board. Many plan to carry out more, better-quality engagements, despite the associated costs, the difficult-to-quantify prospective benefits, and the fact that any fruits from these efforts are bound to be shared with competitors. It is now incumbent upon these managers to enhance disclosure to improve public awareness and understanding of their activities.

1 Throughout this article, we use the term index managers to refer to asset managers who provide index-tracking investments, including traditional index funds, ETFs, and segregated mandates.

2 https://www.unpri.org/download_report/6309. Active ownership for listed equities includes engagement and (proxy) voting activities.

This article originally appeared in the December/January 2018 issue of Morningstar magazine. To learn more about Morningstar magazine, please visit our corporate website.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WJS7WXEWB5GVXMAD4CEAM5FE4A.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NOBU6DPVYRBQPCDFK3WJ45RH3Q.png)