Does Sustainable Investing Help or Hurt Returns?

It's complicated, but sustainable funds more than hold their own on a risk-adjusted basis.

The rationale for sustainable investing makes sense for more and more investors:

- Emphasize material environmental, social, and governance issues that contribute to more-thorough financial analysis

- Focus on the long term, taking into account the impact of decisions on an extended sphere of stakeholders, including the planet itself

- Direct investment to areas that need it as the world transitions to a low-carbon economy

- Encourage more responsible corporate behavior, which makes firms more attractive to talented workers and thus more competitive, enhances intangible value in a social media environment that magnifies corporate missteps, and strengthens confidence in the financial system overall.

But despite that strong rationale, which has attracted trillions in assets under management globally to sustainable investments, one of the main concerns many interested investors still have about sustainable investing is “Will it hurt my returns?”

There are a couple of reasons why this question remains on their minds. First, many consultants and advisors have the misimpression that sustainable investing today is little different than socially responsible investing from two decades ago, which was largely based on aligning portfolios with an investor’s values and relied on exclusionary screening based on products or certain kinds of corporate behavior the investor deemed objectionable.

There wasn’t a great investment rationale for this approach and it was especially difficult for mutual funds to put together a list of exclusions that would satisfy a large enough number of investors to make the funds viable. This approach was more successful for institutional or individual separate accounts.

Over time, as optimization techniques improved, it become easier for portfolio managers to reduce tracking error caused by exclusions and keep performance competitive. But the negative association remained: If you are excluding companies from your portfolio for non-investment-based reasons, you risk underperforming.

Second, sustainable investing today is not an asset class or even a discrete investment style; there are many ways to do it. Unlike other investment areas that have emerged over the past decade--say, commodities or REITs or frontier markets--you can’t readily assess the risk-adjusted returns of “sustainable investing.” Alternatives are somewhat analogous insofar as they include different underlying strategies that are similarly hard to evaluate.

Sustainable investing is more of an overarching investment philosophy that supports a wide variety of investment approaches. Sometimes ESG criteria are used to define an investment universe. One manager may exclude the bottom quartile of companies based on ESG evaluations. Another manager may focus on the top third. Others may hone in on the ESG indicators most material to a particular company. In many cases, ESG is integrated alongside other more-traditional financial factors an analyst must consider. Still another approach may focus on companies that are improving their ESG profiles; some may invest in a company with poor ESG credentials if it is priced right. Some funds are “intentional” about sustainability; it’s clearly stated in their prospectus. Other funds may be incorporating ESG factors into their investment process without making reference to it in their prospectus. Some strategies still use exclusions, such as those that exclude fossil-fuel companies. Others focus on single themes like low-carbon or gender diversity. There are renewable energy funds and bond funds that focus on social and environmental impact. These approaches could be employed within a passive market-cap-weighted strategy or any number of active strategies, which further complicates performance evaluations.

Finally there are institutional asset owners and asset managers, including giants like BlackRock, State Street Global Advisors, and Vanguard, who are active or have become more active as shareholders on sustainability issues without necessarily incorporating them into their security selection and portfolio construction. This year’s proxy season saw asset managers pushing companies to assess and disclose their climate risk to shareholders and to place more women on their boards. They believe companies can enhance shareholder value over the long run by doing these things, but shareholder engagement is not going to be reflected in shorter-term portfolio performance.

With such a variety of approaches to sustainable investing, including those focused on long-term impact that won’t show up in returns today, the performance question is impossible to answer with the same level of assurance that you can with strategies based on asset classes or conventional investment styles.

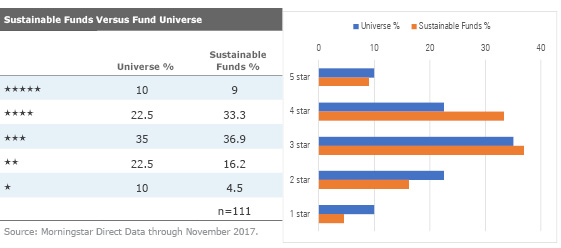

One of the most straightforward ways to assess performance is to compare the performance of public mutual funds and exchange-traded funds that have sustainable intent based on their prospectuses with that of the broader universe. As you can see in Exhibit 1, funds that use ESG criteria or pursue sustainability themes perform well compared with their Morningstar Category peers on a risk-adjusted basis. The current distribution of Morningstar Ratings among sustainable investing funds is skewed in a positive direction, suggesting better risk-adjusted performance. Just above 42% of sustainable funds have 4 or 5 stars, while only 21% have 1 or 2 stars. Based on the normal distribution of the star rating, those numbers should be equal at approximately 33%. The positive skew holds for U.S. Morningstar Style Box categories, non-U.S. stock categories, and bond categories.

This result is all the more impressive given the variety of different approaches to sustainable investing and, of course, the fact that individual fund managers have different skill sets. It suggests that strategies that focus intentionally on some aspect of sustainable investing, on the whole, don’t just hold their own, they outperform the overall universe. Over the long haul, given the compelling rationale for sustainable investing, I expect its performance profile to improve, but you never know--adoption of sustainable investing principles, in whole or in part, could become so ubiquitous that teasing out performance could remain a challenge. If you want to adopt sustainable investing as your investment philosophy, chances are you can find strategies that will meet your performance expectations.

Jon Hale has been researching the fund industry since 1995. He is Morningstar’s director of ESG research for the Americas and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. While Morningstar typically agrees with the views Jon expresses on ESG matters, they represent his own views.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/42c1ea94-d6c0-4bf1-a767-7f56026627df.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EBTIDAIWWBBUZKXEEGCDYHQFDU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CQP5OBZT3NBS7M76RDJCKLIFVM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/42c1ea94-d6c0-4bf1-a767-7f56026627df.jpg)